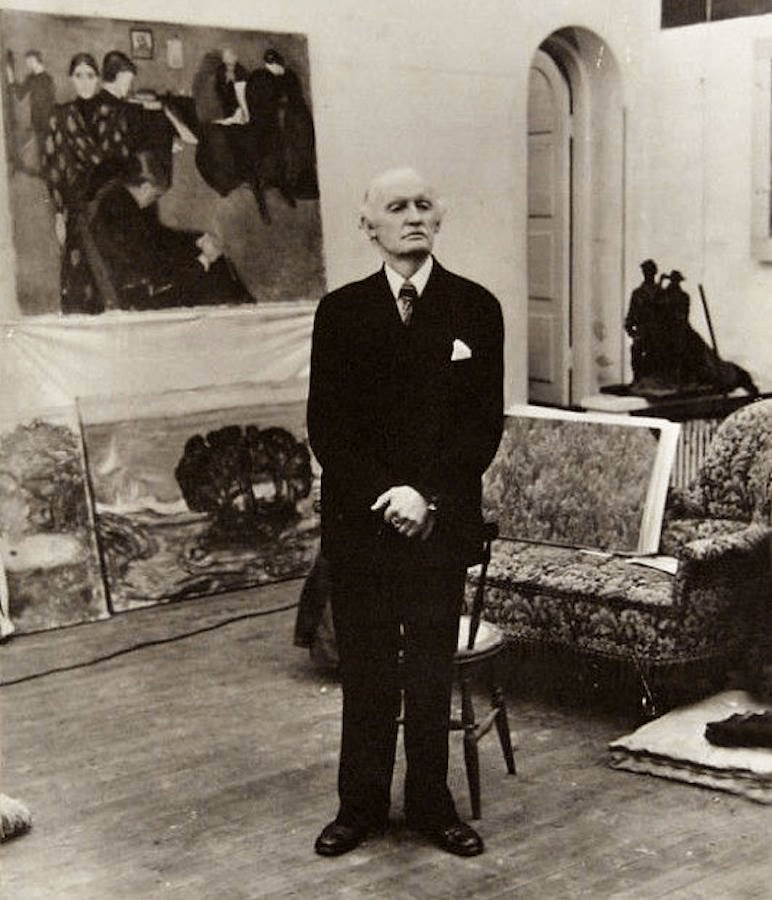

Edvard Munch (1863-1944) is widely recognized not only as a prominent figure in the realm of expressionism but also as one of the most renowned artists across various artistic movements. Throughout the 19th century, he transcended established norms of art, captivating audiences with his unconventional approach that often pushed boundaries and elicited strong reactions. Unfortunately, he was unfairly labeled as a scandalizer and a madman, unjustly branded as the “painter of ugliness” and as the driving force behind what was ominously named “grotesque expressionism.” Nonetheless, this exceptionally talented Norwegian artist had a unique way of delving into emotions, fears, and obsessions, channeling them into his art with remarkable finesse. Such deep introspection and sensitivity were clearly evident in his groundbreaking paintings, characterized by recurring motifs that added layers of depth and complexity to his works. In the following article, emphasis will be placed on a thorough exploration of the latest masterpiece created by this visionary artist.

In October 2021, the Edvard Munch Museum inaugurated its new central headquarters. This distinctive building was located in the port of Norway’s capital, right next to the famous opera house, which was honored with the prestigious Mies van der Rohe Award in 2009. Consequently, Oslo acquired a significant cultural facility consisting of eleven exhibition spaces, providing a venue where admirers of Munch’s art could enjoy the widest range of the painter’s works.

Despite his dissatisfaction with the idea, the artist decided to entrust his artistic legacy to the city. He expressed this horror, stating, “It’s terrible that Oslo will become the home of my paintings.” For a long time, Munch enjoyed greater respect in Germany than in Norway, the country where he lived for a significant part of his life. Munch believed he was more appreciated in the foregin land than in his homeland. In a will drawn up before the outbreak of World War II, he designated a single work to be transferred to the National Gallery in Berlin. However, the events unfolding between 1939-1945 changed the artist’s perception of Germany. This story unfolds in a lesser-known creation titled Explosion.

The artwork is a representation executed using gouache and oil techniques on velour paper – an elegant and delicate material typically used for written correspondence. Edvard Munch often utilized this medium as a base for his lithographs, sketches, and paintings. The dimensions of the work are 65 × 50.9 cm, and it is housed in the collection of the Munch Museum. Its distinctiveness lies in direct connections not only to the events of World War II but also to the personal experiences of the artist himself.

World War II began for Edvard Munch on the fateful night of April 8/9, 1940, marked by the ominous entry of German troops to the capital of Norway. After this pivotal moment, the famous artist found himself plagued by constant anxiety and fear of the impending presence of the Nazis and the threat of confiscating thousands of his precious works from the Ekely area, located on the outskirts of Oslo, where he established his residence in 1916. Well aware of the charm that Ekely held for the Nazis (as evidenced by the occupation of seventeen estates in the area during the war), Munch was acutely aware of the vulnerability that this idyllic location posed to potential wartime actions. Deeply contemptuous of the Nazis, the artist scorned Hitler, calling him “… one great spirit before which all the old specters had to hide in mouse holes.”

Despite the growing risk, Munch made a conscious choice not to evacuate his priceless works from Norway, instead opting for limited precautions, steadfastly remaining in Ekely and ensuring, through a will drawn up in 1940, that none of his estate would ever fall posthumously into the hands of the Germans. This stance contrasted starkly with the provisions presented in a document written before the outbreak of war, underscoring the profound impact of turbulent times on the artist’s mindset and decision-making process.

On a gloomy Sunday afternoon, December 19, 1943, just a week after Munch’s 80th birthday, a catastrophic event occurred when 800 tons of ammunition detonated at the Filipstad quay in the western sector of the Oslo port. The lethal cargo had arrived on board of the German ship Selma. A series of explosions ensued, resulting in the tragic loss of forty-five Norwegian lives, seventy-five German casualties, and injuries sustained by a staggering 400 individuals. The catastrophic chain of events began at 14:45 and culminated in a massive explosion at 16:30, leaving a lasting impact on the Oslo society grappled for the first time with the destructive consequences of war, confronting arbitrary power and the sobering realities synonymous with conflict.

It is in the context of this significant and awe-inspiring explosion that we observe a circular formation of bright yellow light, clearly visible in the background of the artwork Explosion, which, if not for the explicit title attributed to the piece, would likely be instinctively associated with the radiant glare of the sun. The force and magnitude of the explosion were so intense that they reportedly shattered windows in majority of structures in Oslo, including some in the painter’s residence. Reflecting on the event, the artist’s biographer wrote a profound statement, noting that although the damage was confined to a few windows on the second floor, one could imagine Munch perceiving in his life’s work a vulnerability, symbolically embodied in Ekely, akin to the delicate structure of cards susceptible to being swept away by external forces at any given moment. The impact of the explosion extended beyond merely shattering windows in the artist’s home but also expanded into a grand spectacle of illumination cast upon the sky. This unexpected event piqued Munch’s curiosity, prompting him to venture outside and capture this mesmerizing phenomenon on canvas, despite the unfavorable weather conditions of that fateful winter day, characterized by an undesirable mix of snow gradually turning into hail. Recounting the observations of the artist’s sister, Inger, it appears that Edvard Munch spent many hours observing the horizon and meticulously painting a vivid representation of the Explosion. Against the advice of his hostess, Liv Berg, to seek shelter in the basement, Munch remained steadfast in his artistic pursuits, unaware of the tragic fate awaiting him as a result of his involvement in this particular painting.

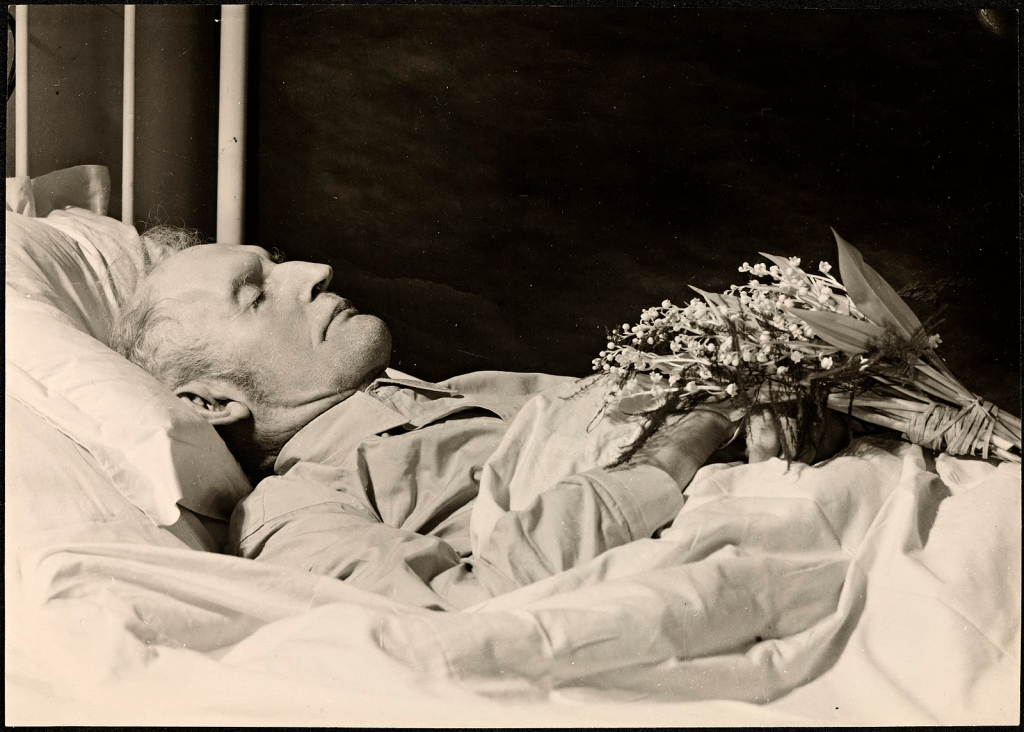

Improperly dressed, the individual succumbed to a cold (as indicated by some reports citing bronchitis or pneumonia) due to exposure to the elements, resulting in his unfortunate death on January 23, 1944 – just thirty-five days after the onset of symptoms. This outcome, though tragic, can be attributed to various factors. Primarily, it is worth noting the advanced age of the artist at the time, which may have made him more susceptible to such ailments. Additionally, the deceased had a history of health issues dating back to his early years. Breakdowns such as bronchitis and rheumatic fever plagued him even in his childhood, posing a serious threat to his well-being and necessitating home schooling. Furthermore, at the age of fifty-five, Munch was afflicted with the Spanish flu, further exposing his already fragile health. Despite illness, the artist continued his work, creating a series of artworks, including paintings, sketches, and lithographs, depicting his physical condition during this challenging period.

Munch’s biographer emphasized that on December 14, just two days after celebrating his 80th birthday, the renowned artist was still in “exceptionally good spirits,” preparing to compose responses to the multitude of congratulatory telegrams that poured in. This task was expected to occupy a significant portion of his time, possibly lasting for several months. However, in a rather unexpected turn of events, just two days after the unfortunate explosion that occurred on board of the Selma ship, the painter’s behavior seemed to undergo a drastic transformation. The vitality and vigor that previously radiated from him appeared to diminish in a subtle, fading glow. Fatigue took its toll on him to the extent that he expressed his weariness, stating, “This war is lasting too long.”

Analyzing the artwork titled Explosion, one can discern the presence of three distinct planes within the composition. The initial plane presents somewhat unclear objects that seem to evoke a sense of familiarity with the artist’s garden furniture, with a recognizable white bench placed on the left side of the canvas. This recognition is facilitated by drawing parallels with other works by Munch, such as Explosion and Landscape with Garden Bench in Ekely from 1942 or the piece titled Gazebo in Autumn, which is believed to be created between 1926-1930.

From a technical and stylistic standpoint, Explosion embodies the quintessence of Edvard Munch’s artistic style. The work is characterized by bold and vibrant brushstrokes, exuding an expressive yet somewhat hasty quality, further reinforcing the impression of its origin. The composition of the work appears cohesive yet dynamic, effectively capturing the essence of the titular explosion at its peak, imbuing the entire piece with a sense of frozen time, akin to a shutter or freeze-frame. These associations are not entirely unfounded, considering Munch’s deep-rooted fascination with the fields of photography and film, which he often utilized as mediums for documenting the bustling life in Oslo and various other Norwegian urban centers.

The color palette employed in the artwork, characterized by almost monochromatic dominance of blue, serves as a dual purpose of emphasizing the depiction of the evening hour and the surrounding darkness, starkly juxtaposed with the nearby explosion occurring just a few kilometers away. Furthermore, it can be interpreted as a manifestation of the profound sense of sadness that permeated the artist’s emotions during the creative process. Considering that Edvard Munch, first encountered such a closeup with the ravages of war, it undoubtedly was a deeply tragic and shocking experience for him. The explosion depicted in the artwork holds significance today as one of the last works that the artist managed to complete before his ultimate demise.