In anime, healing is rarely shown as heroic. It’s slow. Sometimes ugly. And almost never linear. While Western media often resolves trauma with a “lesson learned” or a victory montage, anime tends to sit inside the wound. It doesn’t look away. It lets the silence speak.

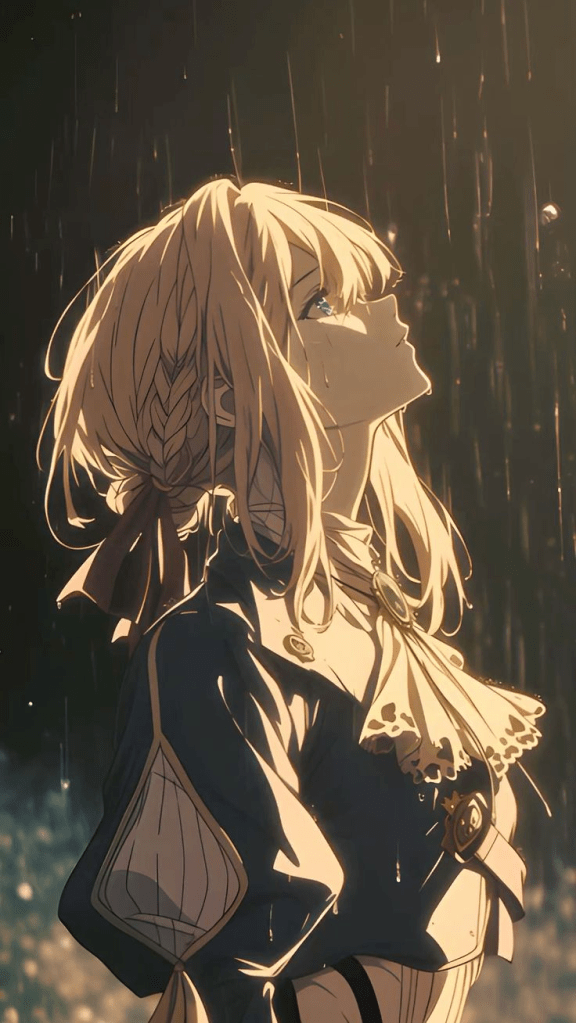

Let’s take a character like Violet Evergarden. When the war ends, Violet is left behind, a child soldier without a purpose, an identity, or even the emotional language to understand what’s happened to her. She isn’t angry. She isn’t broken in obvious ways. She is… empty. Violet’s trauma is not just a reaction to violence, but to being instrumentalized. She was turned into a tool, then expected to live as a person again. And how do you live when you’ve only ever been told to survive? The show refuses to rush her. Violet’s journey toward healing is tender, episodic, and full of setbacks. She becomes an “Auto Memory Doll,” writing letters for others, absorbing their pain, slowly learning how to articulate her own. The pain doesn’t disappear, it’s transformed into empathy. The war took everything from her, but she starts giving others what she never received: Understanding. This kind of healing, delicate, nonlinear, rooted in relationships is echoed across anime.

The Weight of Silence: BoJack Horseman and Self-Destructive Cycles Although not an anime, BoJack Horseman belongs in this conversation. It mirrors the psychological maturity of anime like Welcome to the NHK or March Comes in Like a Lion, by giving us a deeply flawed protagonist navigating a world he can’t emotionally regulate. BoJack isn’t an evil person. But he is a harmful one. He’s someone who, due to unresolved childhood abuse, abandonment, and the pressures of fame, performs self-hatred until it becomes reality. He ruins relationships before they can ruin him. He seeks love in places where he only feels control. What BoJack shows painfully is that trauma doesn’t just hurt. It teaches and it wires you. It builds patterns that look like logic, survival and healing, if it ever comes, doesn’t arrive with a redemptive arc. Sometimes, it just means learning to sit still without hurting someone. BoJack’s pain doesn’t vanish. But his moments of clarity, his attempts to be still, to apologize, to tell the truth feel more valuable than any miracle fix. Healing, in this sense, is honest struggle. Not success.

When Silence Is Louder Than Screaming: March Comes in Like a Lion Rei Kiriyama is one of anime’s most quietly devastating portraits of depression. A professional shogi player by the age of 17, he is emotionally numb, socially anxious, and chronically self-loathing. The trauma here isn’t war or violence, it’s isolation, the slow erosion of self-worth under expectation and loss. The brilliance of March Comes in Like a Lion is how it visualizes the internal. Rei’s depression is expressed through gray watercolor floods, rooms that shrink, sound that disappears. But it’s also treated with patience. There’s no “cure.” Instead, Rei is surrounded by the Kawamoto sisters, by a mentor, by shogi rivals. No one saves him. But they give him reasons to remain. It’s this kind of subtle emotional realism that sets anime apart. Trauma isn’t glamorized, instead it’s contextualized, named, and lived with. Characters are allowed to be weak and we’re allowed to love them not despite their pain, but with it.

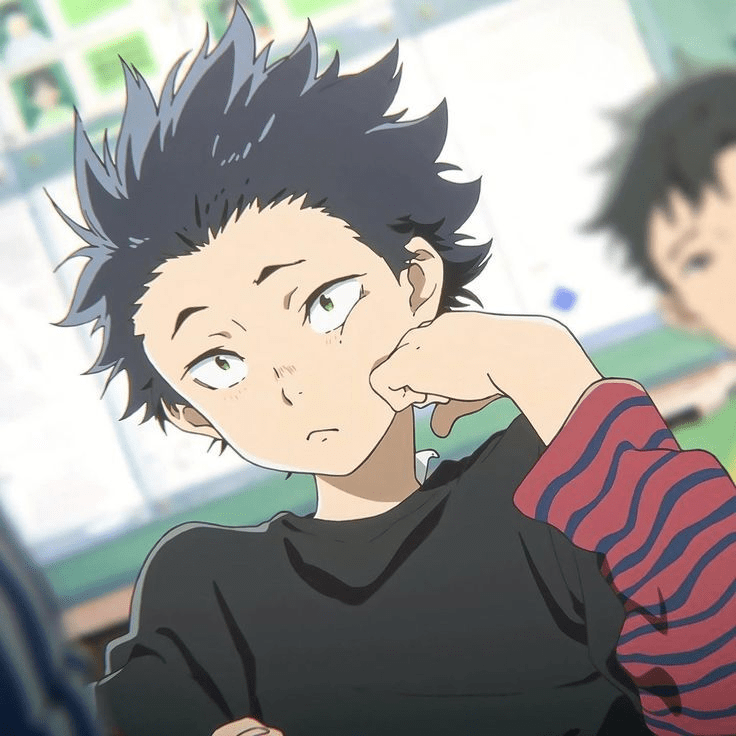

Memory, Shame, and Forgiveness: A Silent Voice Shoya Ishida begins his story with suicide on his mind. Years after bullying a deaf girl, Shoko Nishimiya, he is isolated, hated, and unable to forgive himself. A Silent Voice is not about excusing him. It’s about what it means to live with guilt. How shame calcifies. How self-punishment feels safer than change. Healing, in this film, comes from awkwardness, missteps, and vulnerability. Shoya doesn’t become a hero. He becomes reachable. He learns how to look people in the eye. How to listen. How to want to live again. And perhaps that’s the ultimate theme in all these stories:

Healing isn’t forgetting. It’s learning how to live alongside your scars.

Revenge and Justice in Anime – When Righteousness Turns to Ruin Revenge is never simple in anime. It is a fire that burns twice: once through the world, and once through the person who seeks it. It’s also where morality becomes slippery. Who is right? Who gets to punish? And what does justice look like when it’s soaked in blood?

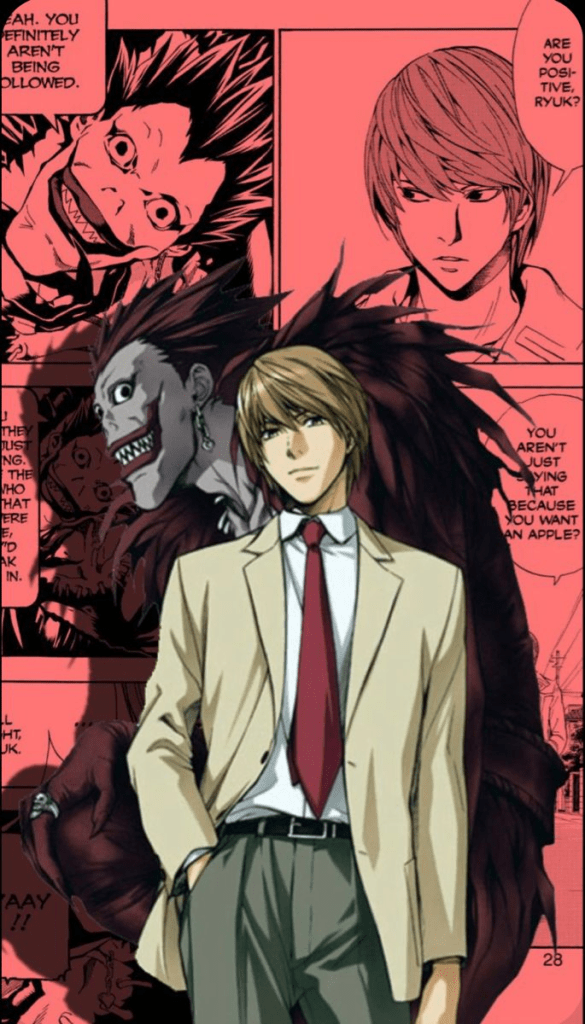

Light Yagami: When Justice Becomes Godhood In Death Note, Light Yagami begins with one intention: to rid the world of criminals. His weapon is a notebook that kills anyone whose name is written in it. On paper, he’s the angel of judgment. In practice, he’s a teenager with a superiority complex and no checks on his power. As the series unfolds, Light convinces himself that he is justice. But what he becomes is a symbol of tyranny. Every time he kills, his ability to justify expands. He starts murdering innocents. Anyone who threatens him is “evil.” Anyone who doubts him is “in the way.” The brilliance of Death Note is how it frames revenge as a moral addiction. Once Light tastes control, he can’t stop. By the end, he’s not a revolutionary but he’s a dictator dressed in divine language.

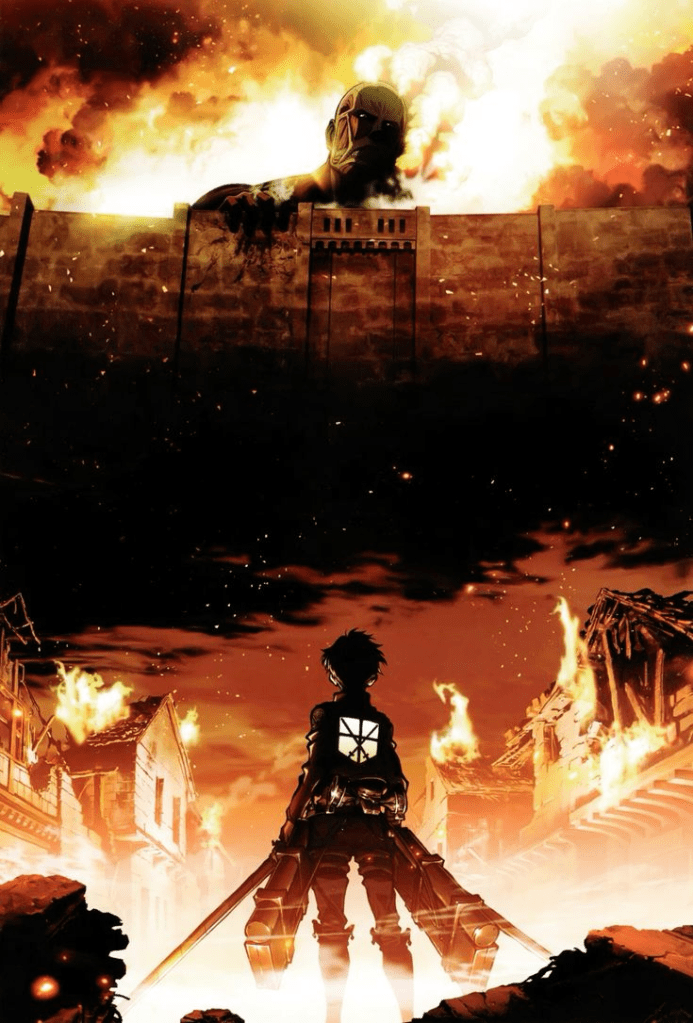

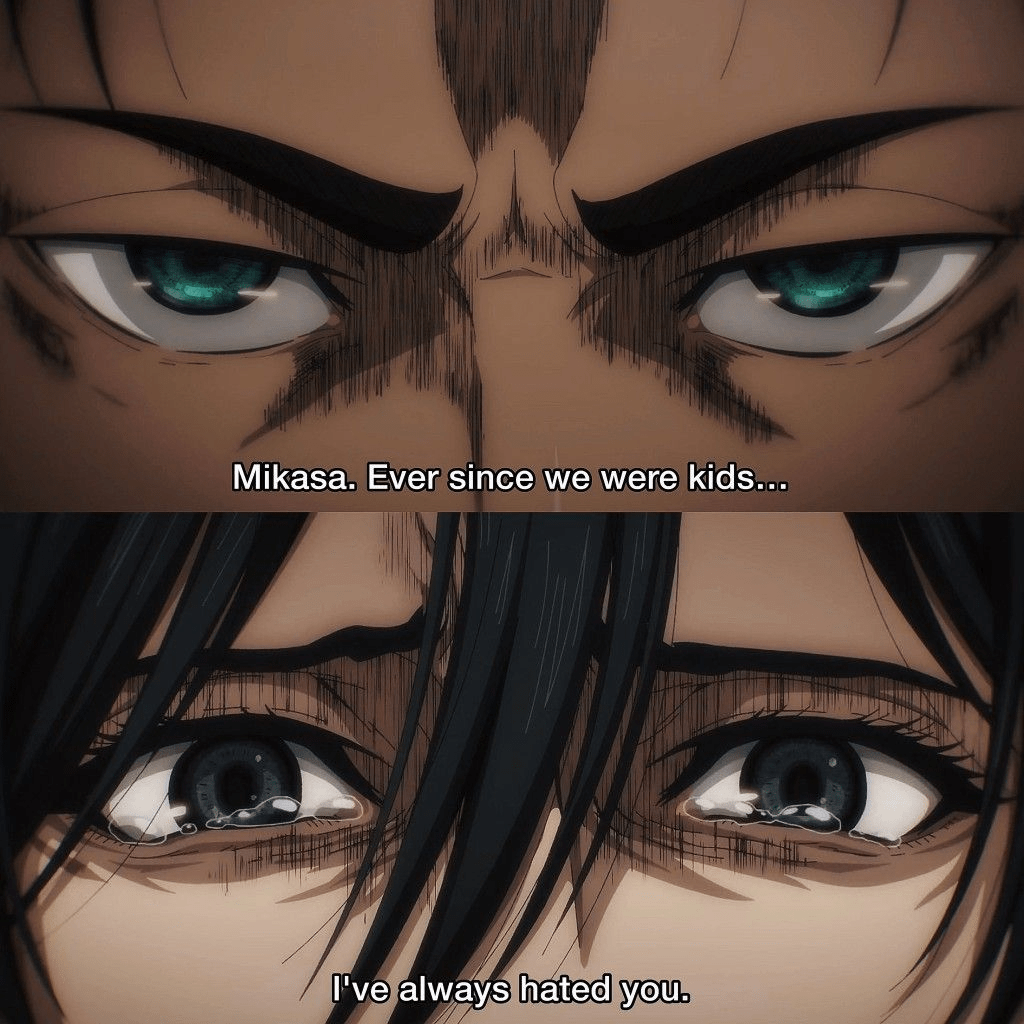

Eren Yeager: A Hero Who Becomes the Threat In the final season of Attack on Titan, Eren Yeager completes a devastating arc. Once the victim of a genocidal war, he becomes the executioner. Believing that annihilating his enemies is the only way to free his people, he plans to wipe out most of the world. The show doesn’t glamorize this. It confronts it. Eren’s “justice” is genocide. His desire for freedom makes everyone else a cage. His old friends aren’t allies anymore but obstacles. The power of Attack on Titan lies in its moral ambiguity. Eren has a point but his solution is inhuman. It asks the viewer: when revenge becomes collective, is there any self left to save?

Johan Liebert: The Monster You Might Understand In Monster, Johan is not an avenger. He’s the embodiment of what happens when someone decides that life is meaningless. After surviving childhood abuse, institutional cruelty, and human experimentation, Johan doesn’t seek revenge he seeks erasure. His goal isn’t to be remembered, but to show that no one matters. Anyway Johan is not a cartoon villain. He’s calm, charismatic, and deeply damaged. The series doesn’t ask us to forgive him, it asks us to look at what created him. And that’s where anime diverges from simple “justice” narratives, it’s not about who deserves what, it’s all about showing what people become after justice fails them.

Hyakkimaru: What Does It Cost to Take Back What Was Stolen? In Dororo, Hyakkimaru is a boy whose body was sacrificed to demons by his father. Eyes, limbs, even his voice all taken. As he slays each demon and regains a piece of himself, we expect a triumphant arc. But Dororo is too honest for that. The more Hyakkimaru kills, the more animalistic he becomes. His revenge restores him physically, but damages him emotionally. In the end, he must ask: Is reclaiming your body worth losing your soul? It’s a profound metaphor. Sometimes revenge makes us whole. But sometimes, it makes us someone else entirely.

Leave a comment