The Baroque period was full of drama, emotion, and grandeur, a time when architecture and sculpture acted like a stage for the story between flesh and spirit. This is especially clear in the sacred spaces of 17th-century Europe, where churches became immersive experiences of light, movement, and meaning. At the center of this drama is the female form: sculpted, painted, and built into architecture as both a vessel and a vision, a presence on earth and an ideal from above.

The female body in Baroque sacred art rarely sits quietly. It’s full of meaning, both sensual and spiritual, vulnerable but strong, earthly yet beyond the physical. It holds a paradox: saint and sinner, pleasure and pain, silence and ecstasy.

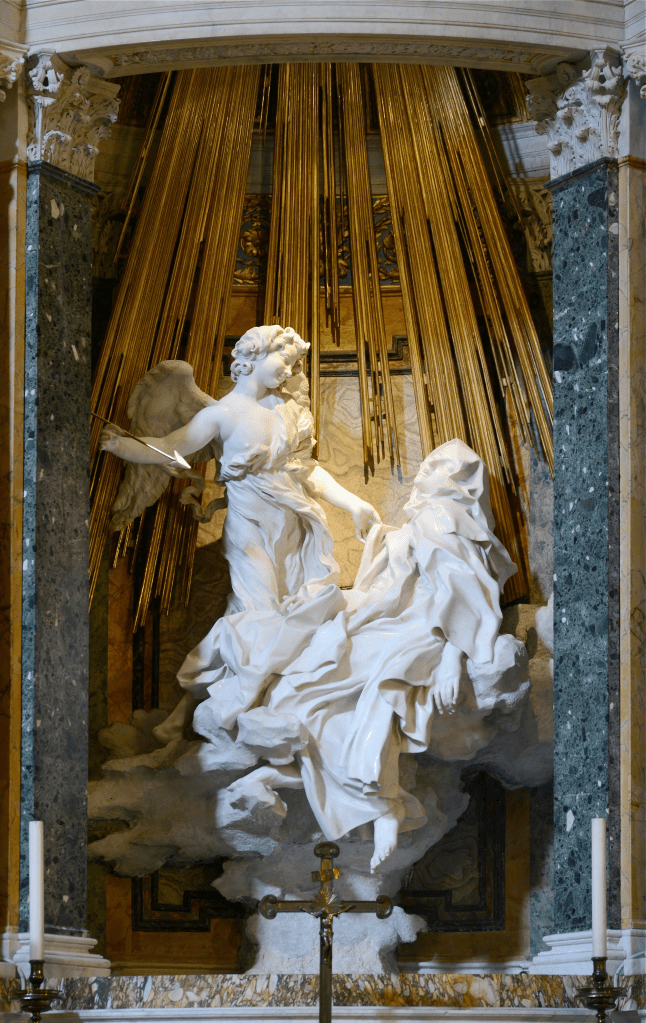

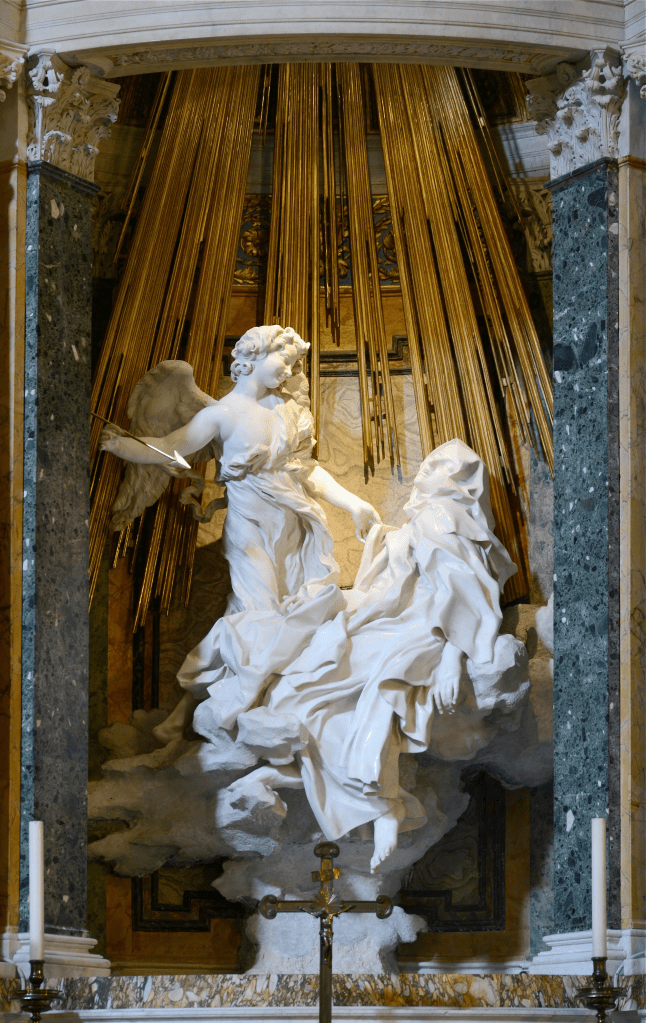

Let’s take Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647–52), for example. This masterpiece perfectly shows the Baroque’s mix of sacred and sensual. Saint Teresa of Ávila is caught in a moment of divine rapture, pierced by an angel’s arrow, an image that blurs the line between spiritual transcendence and physical pleasure. Bernini invites us into a scene where religious devotion feels almost like desire.

But beyond this famous work, there are other, less talked about examples that show the subtle ways female bodies appear in Baroque sacred architecture and sculpture.

–The Hidden Women of the Palazzo Barberini: Allegory and Power in Rome In the Palazzo Barberini in Rome, Pietro da Cortona’s frescoed ceiling bursts with Baroque energy. Among gods and symbols, female figures represent ideas like Divine Providence, Justice, and Abundance. Yet these women carry a quiet tension. Their exposed skin and flowing robes show them as powerful but also decorative, caught between being present and being idealized. They symbolize not just virtue, but also the fragile place women held in early modern society: seen but limited to symbolic roles.

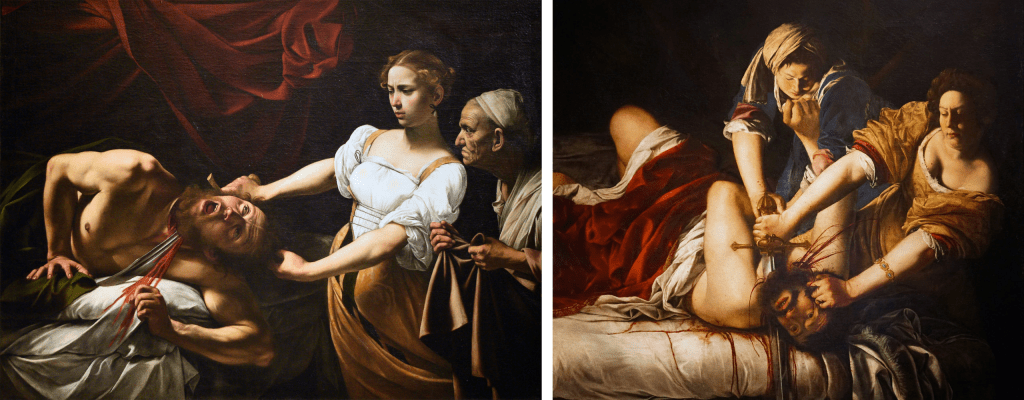

–Artemisia Gentileschi’s Sacred Heroines: Reclaiming the Female Story Artemisia Gentileschi was one of the few well known female painters of the Baroque era. She painted biblical heroines with a raw strength that challenged the typical female images of her time. Her Judith Slaying Holofernes (1614–20) is a violent and gripping portrayal of female power and revenge. Although her work wasn’t architecture, many of her pieces were commissioned for churches, showing women as active agents, not just passive saints.

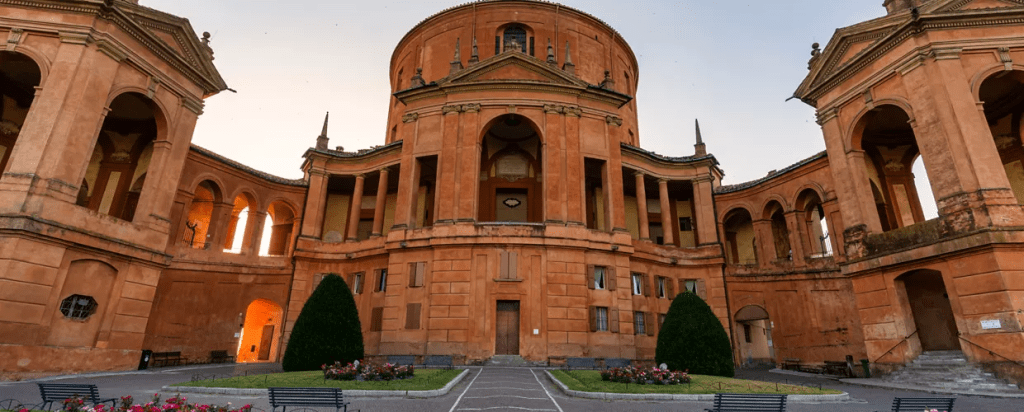

–The Sanctuary of the Madonna di San Luca: A Feminine Presence in Pilgrimage Architecture In Bologna, the Sanctuary of the Madonna di San Luca (finished in 1765) sits atop a hill, reached by a long, winding portico with 666 arches. This architectural wonder ends in a chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary, whose image feels both motherly and regal. The portico itself is said to represent the feminine path of devotion, winding, enduring, and embracing both physical and spiritual journeys. The Virgin Mary here isn’t a still figure; she shapes the space, both as the “Queen of Heaven” and a caring intercessor. The architecture around her becomes a pilgrimage where people physically move through the feminine side of the sacred.

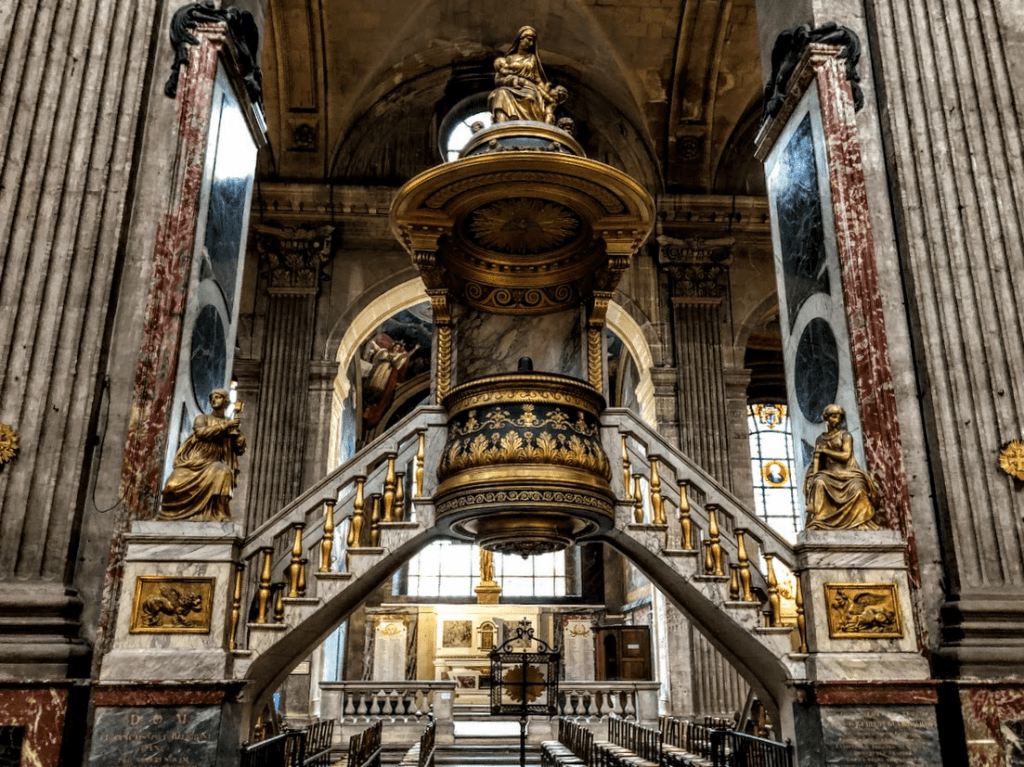

–The Caryatids of Église Saint-Sulpice: Women as Pillars of Faith Caryatids, sculpted female figures that support architectural elements, have roots in ancient Greece but were revived with Baroque flair in European churches. At Église Saint-Sulpice in Paris, female caryatids literally hold up balconies and galleries. They are both strong and decorative, silent but essential. These figures become a powerful metaphor for women’s place in society, clearly important and holding everything up, but often without a voice or real control over the space they support.

Sacred Sound and Sculpted Strength: The Great Organ of Saint‑Sulpice

An 18th‑century masterpiece by Clicquot and Cavaillé‑Coll, blending music, myth, and Baroque presence.

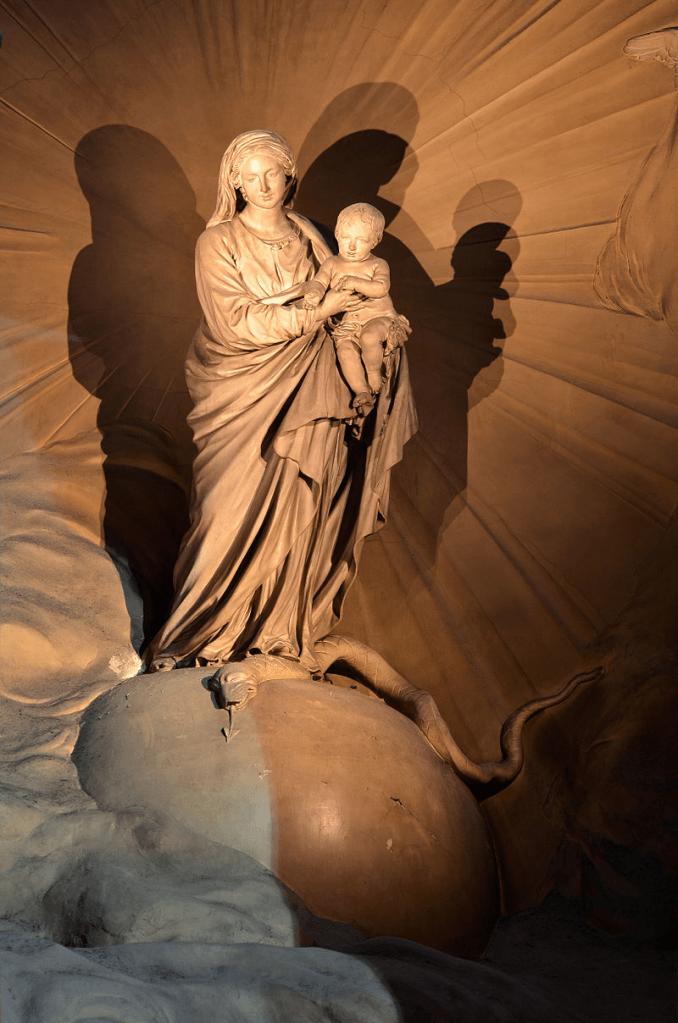

The Virgin stands strong, trampling evil under her feet,Baroque motherhood as power, protection, and presence.

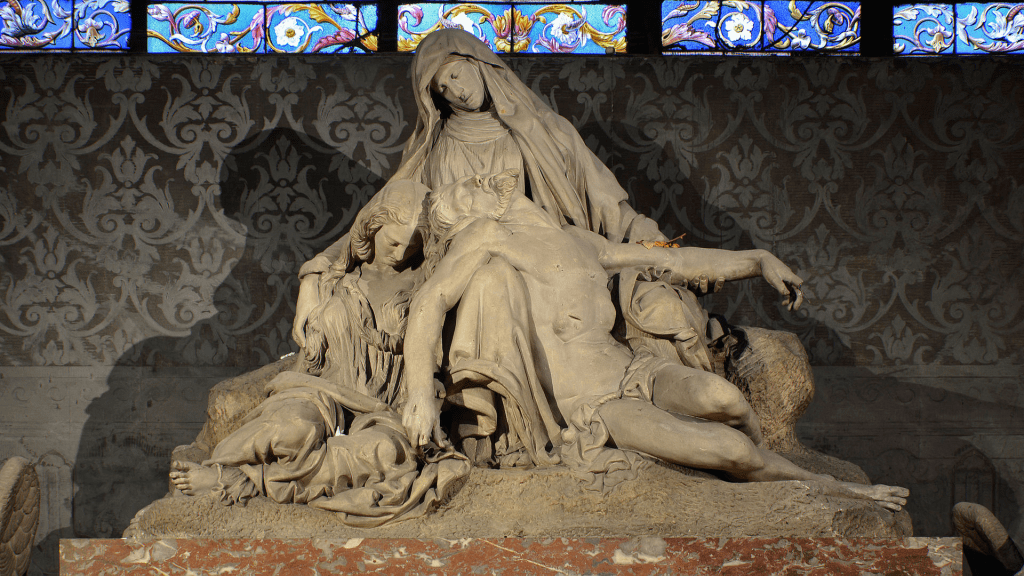

Grief Carved in Stone: The Baroque Pietà at Saint-Sulpice

More than sorrow, this sculpture embodies feminine strength in grief, a powerful spiritual and emotional presence in the church’s sacred space.

–The Baroque Virgin and the Question of Desire This tension between what’s visible and what’s hidden, between power and silence, mirrors the Baroque fascination with flesh and spirit. Female saints and the Virgin Mary are sculpted with flowing drapes that reveal soft curves beneath, faces caught between calm and intensity. Their bodies are admired but also symbols of divine grace, beautiful and holy at once, reminding us that womanhood is both earthly and beyond.

–Reclaiming Flesh in Facade Baroque sacred spaces give us a theatrical, often contradictory picture of women: exalted but contained, desired but controlled, silent but commanding. They hold the body as a place for spiritual experience — but also as a facade made for others to look at. Still, within these limits, the female form shows its complexity, as flesh, spirit, and power. Through architecture, sculpture, and painting, women in Baroque sacred art remind us that gender, faith, and desire are never simple or fixed. It’s a conversation that’s still going on. While the Baroque era wrapped women in layers of sacred symbolism, often controlling, idealizing, and confining, the centuries since have brought big changes. Today, women refuse to be silent muses or quiet pillars of faith. They’re taking back their bodies, desires, and stories with fierce clarity and creativity. From artists and architects to writers and activists, women are breaking free from the facades placed on them, demanding space not just to be seen, but to be heard, felt, and celebrated in all their complexity. The sacred and sensual don’t oppose each other anymore. They come together in the powerful stories women now tell for themselves. As times change, so does the architecture of identity, no longer a prison of expectations but a living, growing structure built by women’s own hands. Flesh is no longer a fragile facade, but a foundation of power, presence, and unapologetic truth.

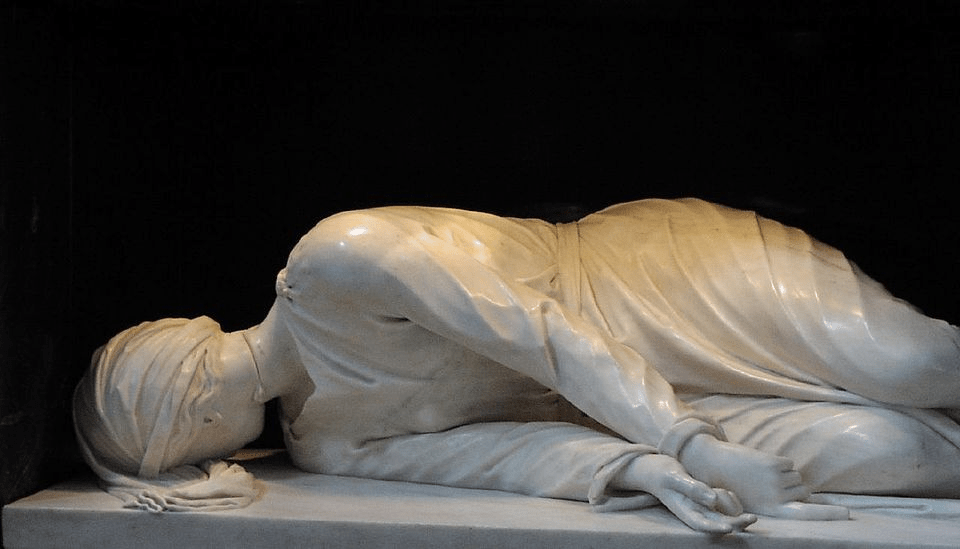

–Saint Cecilia in Trastevere: When Death Becomes Devotion In the Church of Santa Cecilia in Rome, Stefano Maderno’s sculpture of the saint’s body is startlingly realistic. She lies on her side, not idealized or triumphant, but soft, human, and vulnerable. Her neck bears the mark of martyrdom, and her dress clings to her body in a way that is both respectful and subtly sensual.

Saint Cecilia in Eternal Repose

Stefano Maderno’s sculpture shows the saint’s body as it was said to be found: incorrupt, serene, and turned away. Death becomes devotion in marble.

The softness of marble folds echoes the saint’s quiet dignity. Even in death, she resists collapse—clothed in faith and strength.

This isn’t a dramatic display of ecstasy or spiritual power. It’s quiet, still, and in that stillness, we’re forced to confront a difficult truth: Cecilia’s suffering is made beautiful. Her death becomes devotional and her body becomes a symbol of piety, not because of what she did, but because of what was done to her.

–The Cornaro Chapel: Who Is Watching Whom? In Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, Teresa is caught in a moment of divine rapture, her body arching, her face overcome, pierced by an angel’s golden spear. The image is famous for its erotic undertones, often interpreted as a merging of physical pleasure and spiritual experience.

But something else is happening around her. On the sides of the chapel, life-sized sculptures of male patrons (the Cornaro family) are built into marble balconies, watching the scene. These spectators are carved into the architecture itself. Their presence reminds us that Teresa’s body, her experience, her vision, is not entirely her own. It’s something to be viewed. Displayed. Validated through male eyes. Even in a moment of supposed spiritual freedom, she’s surrounded by a structure that controls how she is seen.

Bernini’s theatrical masterpiece stages not only Teresa’s divine rapture, but also the spectators, the Cornaro family—frozen in carved balconies, as if witnessing the sacred and the sensual collide.

–The Virgin of El Panecillo: Motion and Majesty In Quito, Ecuador, a massive statue of the Virgin Mary stands atop El Panecillo hill. Unlike many European representations of Mary as still and passive, this Virgin moves. She’s stepping forward, with wings outstretched and a serpent crushed beneath her feet.

This is not a quiet, decorative Madonna. She’s active and powerful. And she looks directly at the city below, not with softness, but with purpose.

This image is important because it breaks from the usual visual language of feminine sacredness. She’s not there just to be loved or obeyed, she protects, acts, and leads. It shows that sacred femininity can be forceful, political, and present in the world—not just a symbol of inner purity.

At her feet lies the defeated serpent, an echo of Revelation’s Woman of the Apocalypse. This detail emphasizes Mary’s role as conqueror of darkness and spiritual protector.

–The Veiled Christ: What Is Revealed Through Covering Although not a female figure, The Veiled Christ by Giuseppe Sanmartino offers something important to the conversation about how sacred bodies are shown. The sculpture depicts the dead Christ covered by a thin marble veil that clings to his body. The folds of the cloth are so finely carved that they reveal every contour of his flesh.

Seen from above, the sculpture’s contours and shroud harmonize into a chiaroscuro symphony, light sculpted in marble.

This technique, showing the body through layers was common in Baroque sculpture, especially with female saints and the Virgin Mary. Their bodies were “covered,” but the folds of the fabric often made their shapes more visible and idealized. In many cases, modesty becomes just another form of exposure. The body is shown, but always through the lens of male craftsmanship, male vision, male control. What is hidden is not really hidden. It’s framed as something sacred, but also something to be admired aesthetically.

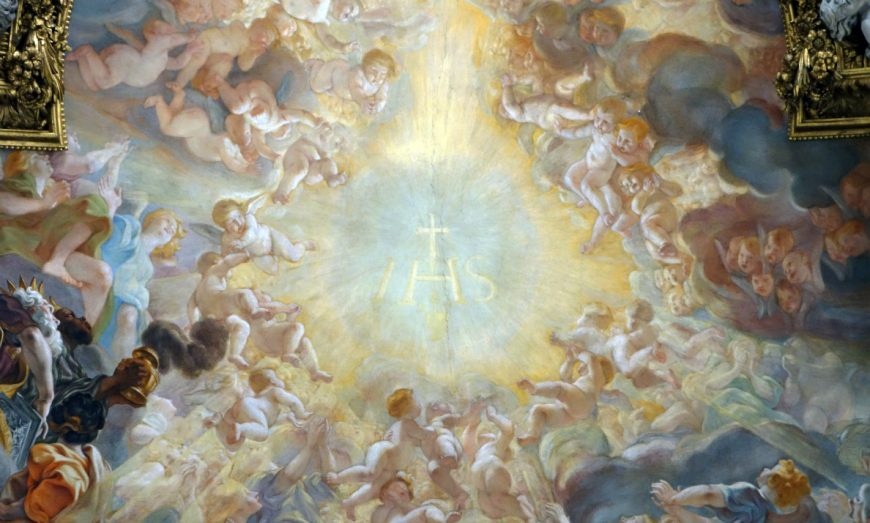

–The Ceiling of Il Gesù: Women on the Edge of Glory In Rome’s Church of Il Gesù, the ceiling fresco by Gaulli shows souls ascending to heaven and falling into hell. It’s chaotic, powerful, and full of movement. Among the saved are several women, anonymous, half clothed, their faces tilted upward in awe.

Illusion of Heaven: Fresco Meets Sculpture Gaulli’s genius merges stucco angels with painted ones, breaking the frame so that stone and paint vanish into a single celestial vista.

They’re part of the divine story, but they’re not the protagonists. They don’t speak or act. They just rise. Their presence matters but it also reminds us of a recurring theme: women as symbols of purity, redemption, or sin, rather than as individuals with agency. The Baroque used the female body to represent ideas, often without giving the women themselves a place to act or speak from.

Foreshortened Women on the Brink

Anonymous female saints and souls hover at the threshold, half-clothed, uplifted, poised between earth and heaven in furious foreshortening.

Ascending and the Damned Falling Divine figures rise toward salvation while anguished souls tumble from grace, a Baroque theater of salvation and judgment.

Leave a comment