The exhibition Sztuczne Zestawienie Rzeczy Ważnych by Marina Dysh.lova opened on March 14 at the Art Space B383 in Warsaw. As the curator and direct creator of this exhibition, I want to share with you the deeper context behind the show and some of the hidden meanings within it—not only through my perspective, but also through the lens of the artist herself. I’ll aim to approach this critically and reflect on the exhibition in a way that highlights its key points, and include some of the artist’s responses in quotes.

The exhibition was an experiment for me—something that, like a sponge, absorbed everything that is typically expected of a “trendy” exhibition. It includes ecological issues, personal memories from 2015–2021, the time when I used to visit the NCCA (National Center for Contemporary Art) in Minsk. And in the midst of all this, one painting faced an unfortunate fate. But let’s take things one step at a time.

“The project Sztuczne zestawienie rzeczy ważnych is an attempt to grasp a paradox: in searching for the answer to ‘What is Paradise?’, a person deforms everything they touch— be it morality, social norms, or ecology.”

(From a conversation with the artist)

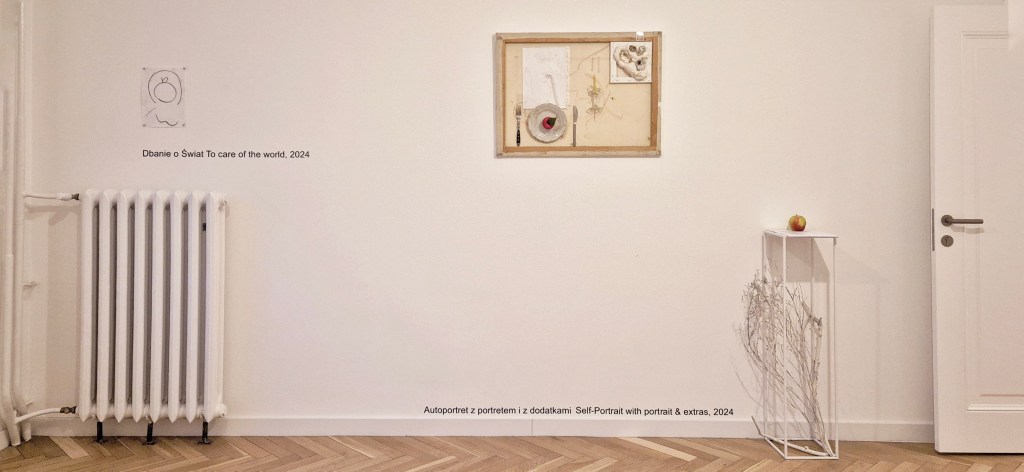

As described in the curatorial text, the main space at Art Space B383 was created in collaboration with Hashtag Lab, a space dedicated to contemporary music. It was my responsibility as a curator to blend these two contexts together. The exhibition itself contains 12 works across two rooms, presenting a dialogue of sorts about dodecaphony in modern music, expressed through visual art.

“The only thing I want to recreate, to find, to glimpse even briefly, is what life must have been like at the very beginning. What did the first humans do? How did their days unfold? What size were the tigers? How did birds sing in that distant time? I want to recreate only the form, to express my feelings about it, to immerse the viewer in contemplation, and perhaps intensify the images of that once pristine reality.”

(Dysh.lova)

Dysh.lova’s interpretation of Paradise is bold and packed with meaning. She doesn’t approach it as a utopia, but as a conceptual space where opposites, like life and death, good and evil, light and darkness, coexist in tension.

“I see humans in Paradise as the first force to create life on Earth—comparable to the life we know today: day and night, light and darkness, good and evil. A symbiosis of polarities. If we rely on biblical accounts, one of the few sources about the origins of life, we might view Eve’s bite of the apple differently. She brought pain, fear, and suffering into what was once a perfect haven—and in doing so, made it more valuable. Can we destroy something we’ve never seen? Can we restore something we’ve never ruined?”

(Dysh.lova)

Her use of materials underscores the same duality. She works with everyday objects in a similar way to Władysław Hasior, but in addition to traditional mediums like painting, Dysh.lova incorporates construction foam, a delicate and volatile medium that demands more attention than oil or acrylic.

“I’ve worked with graphics, sculpture, painting, and directing. But none of those disciplines gave me as many tools to convey the powerful, childlike curiosity I feel inside. The process of creating a piece—whether it’s assembling the materials or ‘giving birth’ to it—usually takes no more than an hour. Working with construction foam involves an active interaction with the material—it dries quickly, takes shape unpredictably, and needs special care. I love the alchemy of it—running around the canvas, searching for the right color, picking the perfect plate or spoon. It’s like recreating Paradise in laboratory conditions—artificially, by touch.”

(Dysh.lova)

Personally, I tend to avoid popular themes when curating exhibitions. Maybe that’s why I’m still seen as something of an underground curator. However, when the idea of integrating ecology into this exhibition was proposed, I initially resisted. But after some reflection, I decided to embrace it. This contradiction became part of the exhibition itself.

If I were to describe the exhibition in a single phrase, it might be: the search for harmony in chaos —attempting to build a new paradise while destroying life around us. The works seemed to embody that conflict, creating a unique visual tension.

And then came the Easter eggs.

In my search for inspiration to frame Marina’s assemblages, I recalled my visits to the National Center for Contemporary Art in Minsk, where I once saw a phrase written above eye level in the corridor of their Nekrasova branch: “A mistake was made.”

No one knows where this phrase came from—it probably remained after a past exhibition. But anyone who’s visited this space remembers it. I decided to leave a similar trace of my own cultural code in the exhibition. Not everyone will understand it, but that’s part of the point. The phrase was placed on one of the walls at the Warsaw venue, intentionally hidden and enigmatic.

The phrase, “A mistake was made,” is paired with a misspelled painting title written in Polish. This was not an accident. The mistake is part of the message—conveying not just error, but a critique of “brandiness,” a commentary on the imperfection of language itself.

When curating the show, I selected not only assemblages, but also a painting and drawings. But one particular foam piece gained a second life in the process.

“I treat what’s already realized with extreme care—it’s a tender story woven from deep personal experiences and themes that truly matter to me. My special love is for the painting Portret Ewy, czyli druga strona bycia Ewą z Raju. It’s about the unconditional, all encompassing love of a mother—love so powerful you would feel it even from thousands of kilometers away. It’s about learning how to live this life, because we’re all here for the first time. And that love was already here before us. Now the painting has changed—not in its physical form, but in the meanings it conveys. It’s gained more value, like day and night; light and darkness; good and evil.”

(Dysh.lova)

In reflecting on this exhibition, I realize it couldn’t exist without this layered conversation: artificiality and memory, myth and material, mistake and care. This text, in many ways, is my own response and intervention within that ongoing conversation—a metatext, for a metaparadise.

Leave a comment