By Natalia N.

There’s a particular kind of silence that lives in the paintings of Anastasia — a hush between memory and imagination, joy and melancholy. The 23-year-old artist, currently in her fourth year at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków, explores the untranslatable feeling of saudade — a Portuguese word that describes a deep, aching nostalgia for something lost, or maybe something that never fully existed.

With a background in art history and nearly two years spent studying at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence, Anastasia’s work has already been exhibited twice in Italy. Her portraits — often close, blurred, intimate — feel like visual echoes of emotions we’ve all felt but struggle to name.

We sat down to talk about impermanence, the poetry of absence, and why painting is her way of preserving what time always tries to erase.

Anastasia, your paintings seem to exist in this very delicate emotional space. What’s at the heart of your work?

I try to capture saudade. It’s a word that doesn’t translate easily, but it lives in all of us — that longing for moments that passed, or for something that maybe never really happened, but still feels real. It’s a kind of sadness, but also beauty. I paint to hold onto those fleeting emotions — the ones that are already disappearing while we try to remember them.

That’s such a poetic starting point. How do you translate that into your visual language?

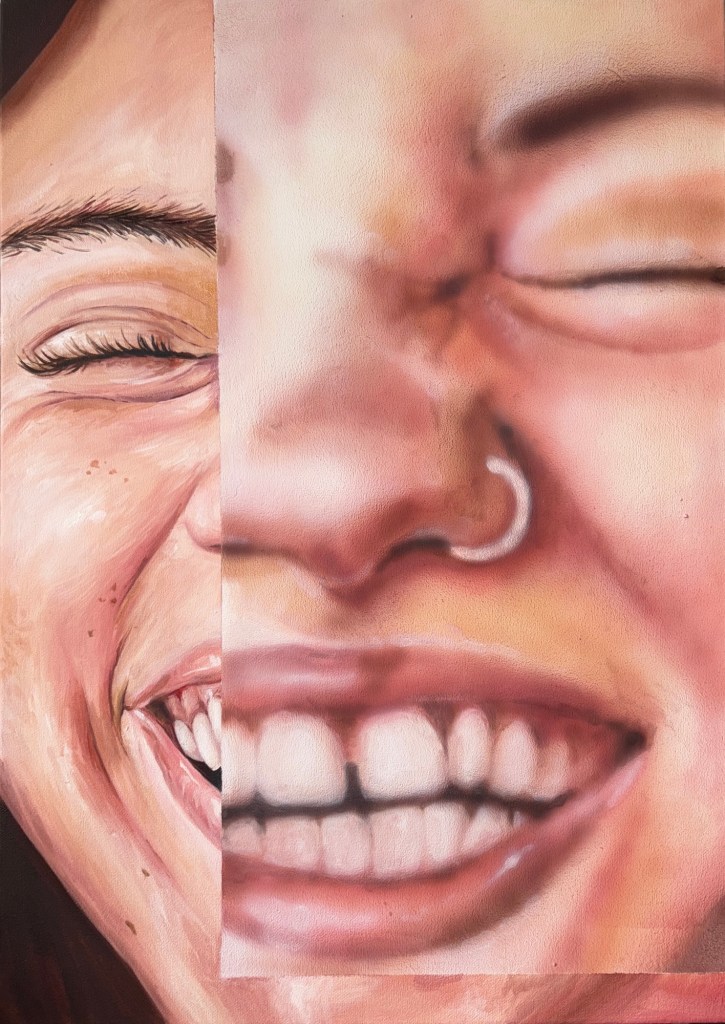

I focus on fragments — a smile, a hand, an eye. I’m interested in those partial memories that stay with us. When we remember people or moments, we don’t remember the whole scene. We remember feelings, colors, small details. I paint in soft tones and blur the contours because I want it to feel like memory: intimate, tender, a bit uncertain.

You studied art history before fully diving into painting. How does that background influence your practice?

It shaped how I think. Art history taught me how artists dealt with emotions centuries ago, how light was used to express vulnerability, or how gesture could carry meaning. But when I paint, I don’t think about theory — I follow a feeling. Painting is more personal for me. It’s not academic. It’s about remembering with the body, not the mind.

You spent almost two years in Florence. What did that experience give you?

It gave me time. Time to observe, to learn, to slow down. I studied at the academy there during Erasmus and held two exhibitions. Being surrounded by that kind of art — by frescoes and marble and old stone — changed how I see the world. It taught me to appreciate silence, texture, light. It made me want to paint not just what I see, but what I miss.

Your portraits feel both deeply personal and universal. Do you work from people you know?

Sometimes. Sometimes it’s people I love, and sometimes it’s just a feeling I project. I don’t always want the face to be recognizable — I want it to be familiar to anyone who looks. Like déjà vu. Like something you once felt but can’t explain.

There’s a strong emotional atmosphere in your work, but it’s never dramatic. Why do you keep things so quiet?

Because I believe that the quietest moments are often the most powerful. A glance, a breath, a gesture. I don’t want to overwhelm the viewer — I want them to lean in. To feel like the painting is whispering something just to them.

What are you working on now? What direction is your art taking?

Right now, I’m working on a series where each painting holds a tension between clarity and blur — one part is sharply defined, almost hyperreal, and the other dissolves into softness, like a fading memory. It’s my way of capturing the fragility of a moment, how something can feel vivid and distant at the same time. This contrast reflects saudade — that longing for something you can almost touch, but it’s slipping away even as you try to hold onto it.

Finally — if someone stands in front of your painting, what do you hope they feel?

I hope they feel something they can’t explain. A memory that isn’t theirs — but somehow is. That quiet ache. That’s enough.

Leave a comment