The Arnolfini. Bristol, UK.

The Arnolfini is a progressive interdisciplinary contemporary Art Gallery and space on Bristol harbour-side, established in 1961 by founder Jeremy Rees, who named the gallery after his favourite painting by Jan Van Eyck, the Arnolfini Wedding portrait of 1434. Now a venue of worldwide significance, exhibits may be viewed over three floors. The ground floor also hosts a friendly cafe bar with an interesting menu serving brunch & lunch, and an excellent bookshop, in addition to gallery space.

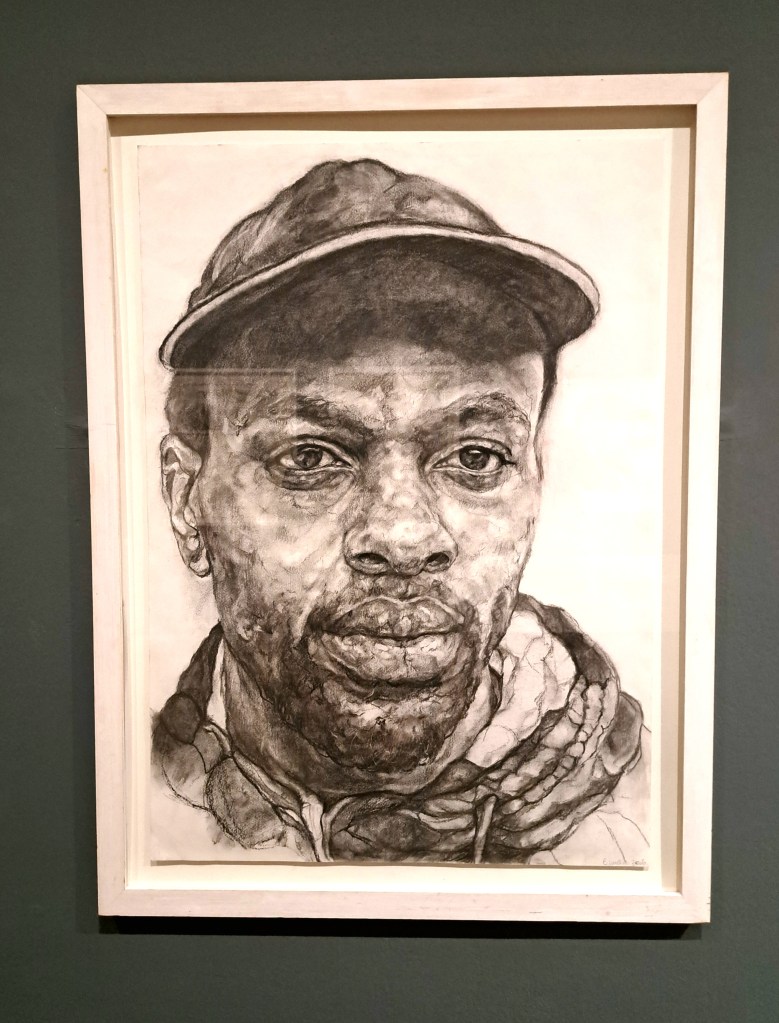

The current exhibition showing Tate Prize nominee Barbara Walker MBE RA, relates to her historical and recent research, the development of associated perceptions and experiences emanating from that research, and her own personal experiences and outrage at points in time, all of which relate to the lives of black individuals and resettled groups, standing alone and within communities. The black subjects are sensitively drawn in graphite and charcoal in traditional style, on large papers, emerging with print processes, and paint on canvas. This is fascinating work following a common thread, where original ideas emanate from an emotional starting point and a willingness to be the visual voice of perceived and very real fear, exclusion and injustice in a black community. These are heartfelt pieces where unspoken realities resulting from a question of colour in society, are ably conveyed though Art.

As a starting point for the embossed series of prints, Vanishing Point, Walker specifically sought and chose paintings by prominent sixteenth and eighteenth century artists to use for this project, where black people were included in these original paintings, but were portrayed as being of lesser importance than their fair-skinned counterparts, and were often observed in the background or in useful service situations in these particular works. Walker has used the templates of these paintings for her inspired photopolymer gravure embossed prints series, where an effective bas-relief printmaking technique leaves only the colourless outline of eliminated white sitters, ghosts if you will, where they were once prominent subjects in these old master paintings, leaving only Walker’s preferred black subjects to feature in the remade pieces. This is done clearly to emphasise a point being made with regard to race and power historically. The result is a predominantly white embossed artwork often with only one or two smaller black figures remaining and re- illustrated by Walker, and, it could be argued that the little that is left, leaves the artwork somewhat out of context, which may be the point. This is a clever much admired conceptual idea, and yet somehow leaves an imbalance of composition to the eye despite its redrawing and the excellence of technical outcomes, again probably intentional.

Walker’s established drawing skills are without question superb. In the Burdon of Proof series, the sitters are carefully drawn over enlarged magnified documents, emphasising the perceived importance of these official scripts, where the person becomes an integral but lesser part of these compositions, intimating that the document is seen as of greater importance than the person owning it. This original idea portrays a disconcerting injustice in part relating to the recent Windrush scandal and demonstrating another effective conceptual idea from the artist.

All Barbara Walker’s drawings and paintings are of black people past and present, faithfully represented visually as they once lived at a moment in time, and drawings also show us how selected black people appear today, with any white counterparts deliberately eliminated from the scenes or re-translated drawings. Sometimes subjects may have a personal link to the artist, but often a random element is introduced where black strangers from old photographs or articles are chosen at will and placed within a composition for convenience, where actual historical identity is unknown, and, as the exhibition continues in this vein onto the next floor, the concept could begin to feel like obsession, where there seems to be an unnecessary elimination of all white people in all of her works, whitewashed out, where perhaps there wasn’t an imposed prejudice entirely, who knows, or a feeling of lesser rank situation, experienced by all of the black people illustrated in her works, but the concept remains king throughout. There may be some presumption here imposed upon those who can no longer speak for themselves.

It has to be said that Black and white people have not always been so obviously segregated, but today to speak of colour has become a sensitive topic given modern implications of injustice and power policies, but black and white have been living happily side by side in communities in Britain for many years, with equal advantages. The stop and search policy, influential in this exhibition with reference to Walker’s son, has much to answer for in society today. Michael Jackson once said, it doesn’t matter if you’re black or white, which, is surely a good message moving forward. The burden of concept using mechanical exclusion for anyone with a white skin does seem to me to be stretching the point a bit, albeit cleverly, and it could be argued that it has become a slave in itself to a concept, which may only continue bitter separation within communities.

With the Burdon of Proof series, I can see clearly how so much recent injustice has led to these works as a representative statement, especially with the recent mismanagement and misrepresentation of young black men today on our streets, to site the Lawrence crime incident which has prompted concerning situations where mothers’ worry and grieve, and differences become highlighted in a world where justice for all often seems like justice for none. Young white men suffer too, and also seem to be more unrepresented today. The analogy of discrimination becomes in itself discrimination if only seen through a singular life-lens, where healing needs to be viewed through the wider lens of integration and communication. The persistence and insistence of delving into the past, and potentially rewriting narratives, may become the real problem if we are stuck there and cannot move forward together as one.

Walker had said, ‘I always have one foot in history and one foot in contemporary practice. I always go back to history. I look back and re-enact history to go forward.’ It is unclear to me from these works, technically good, as they are, how to see that message in this exhibition.

Inspired concepts and ideas are evident throughout Barbara Walker’s illustrated works, where the use of original and alternative ideas stand proud as evidence of promoting contemporary black practice today, all beautifully illustrated in her established style to convey her messages in new and interesting ways. Although promotion of black art is prevalent in these works, skill and talent are given, accepted and appreciated by all peoples, communities and institutions in Britain today, and it seems somehow these works are already consigned to another recent past and are already history.

Walker is also showing a series of oil paintings on canvas which can be viewed in the second floor gallery. The outstanding piece for me is titled ‘Attitude’ and is an excellent painting of a young girl, where the details are sensitively and beautifully painted by Walker. However, this work seems quite different in style from her additional paintings being shown alongside it in this space.

All these works are scenes and insights into black lives in various every day situations and are painted in strong colour tones, but without the sensitivity of ‘Attitude’. Although good enough works in themselves, they lack any connection to the concepts or ideas which formed the basis of Barbara’s more progressive drawn pieces and original prints, and show a less progressive technical style than seen in her conceptual pieces.

A surprise addition to the exhibits is a complete room which is wallpapered on theme with printed strips, as an expansion and extension to the ideas relating to the black Windrush characters, all printed in blue tones, featuring drawings and recording of faces from Walker’s portfolio surrounding the room in a repeated pattern.

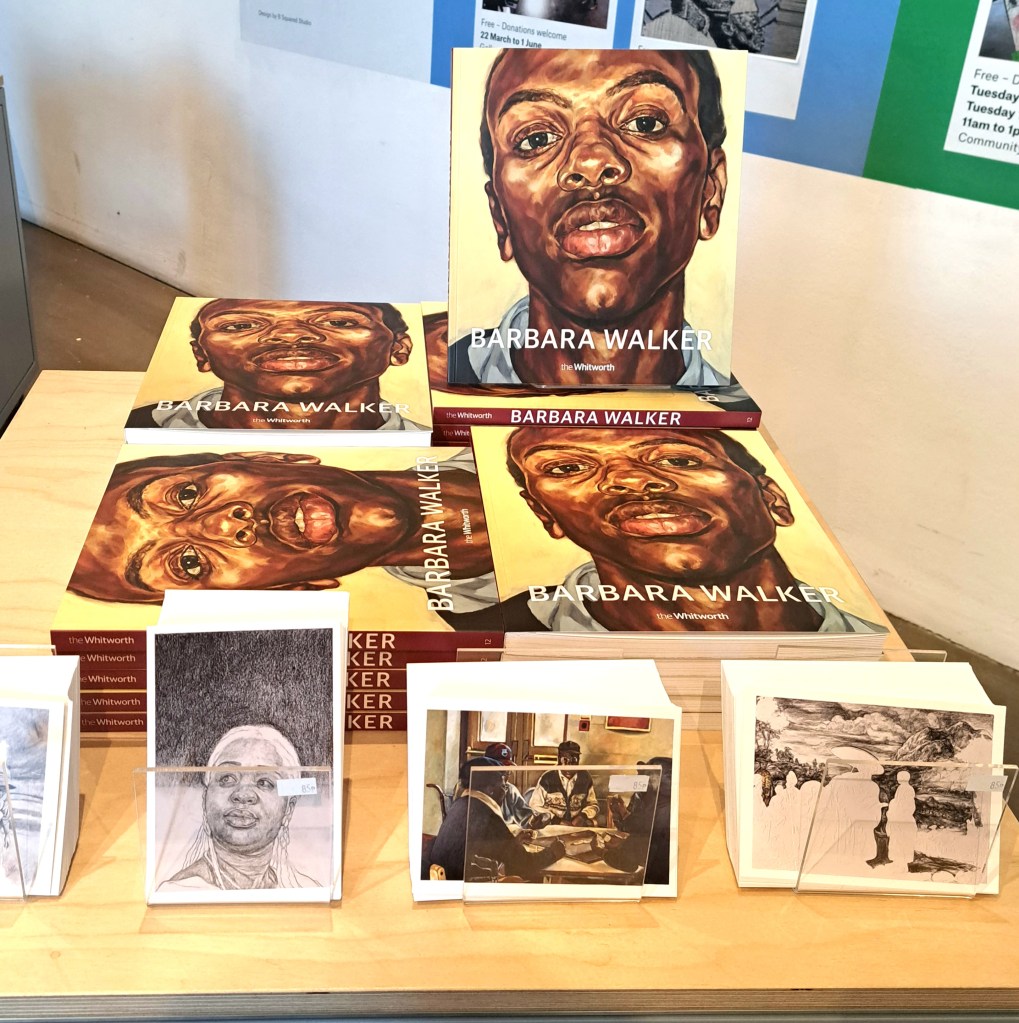

The Barbara Walker Exhibition runs from 8th March until 25th May 2025 and is a must see for the excellence of technique in bas-relief print, charcoal and graphite, with use of original conception.

The exhibition was organised by the Whitworth, University of Manchester & the Arnolfini. Initiated by Leanne Green & curated by Poppy Bowers & Hannah Vollam. Works from public and private lenders & support from The Cristea Roberts Gallery, The Jamaican Society, Manchester, The Black South West Network, The University of West of England, Ashley Clinton Barker Mill Trust & Arts Council England

Available in the Arnolfini bookshop is the notable book, ‘The Time is Always now; Artists reframe the black figure’, by Ekow Eshun, which includes images from Barbara Walker’s works and numerous other artists at the forefront of Black Art Practice, and includes ‘VOICES’, Reflections on black bodies and lives, by authors, poets and Scholars’.

A Review by Deanna de Roche 2025

Leave a comment