The presence of women in art has been shaped for centuries in response to social, religious, and cultural norms, often dictated by patriarchal systems. Women in art have not merely been depicted as individuals but rather as symbols of broader ideas—ranging from the sacred to the sinister, from nurturing figures to forces of destruction. Female archetypes such as goddesses, witches, and revolutionaries reflect the evolving perceptions of women’s roles in society, their relationships with men, and their own identities.

Throughout the history, artistic representations have transcended the mere physical portrayal of women, instead presenting them as beings of immense power—both creative and destructive. These archetypes are deeply embedded in cultural traditions, and their presence in art serves as a commentary on how society has viewed and continues to view women. From the Madonna to the femme fatale, from mythological goddesses to modern feminist icons, these depictions have conveyed values, norms, and fears regarding the female nature.

Woman as an Ideal

For centuries, particularly in ancient and Renaissance art, women symbolized ideal beauty, desire, and sanctified bodies. In ancient Egypt, Isis was portrayed as a guardian and a mother, while in Greece, Aphrodite personified sensuality. During the Renaissance, women became objects of artistic admiration—Raphael’s Sistine Madonna and Titian’s Madonna and Child emphasized both their spiritual purity and physical beauty. Michelangelo’s The Creation of Eve and Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus idealized women, making them the focal point of artistic fascination while simultaneously subjecting them to the male gaze. Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa presented an enigmatic female image that continues to captivate researchers and audiences alike. Similarly, Botticelli’s Primavera depicted an allegorical vision of femininity, full of delicacy and harmony, aligning with Renaissance ideals of beauty and perfection.

Woman as a Threat

Conversely, women have also been portrayed as a danger—often associated with sensuality, chaos, and destruction. The femme fatale archetype emerged in 19th-century literature and art as a symbol of the mysterious and seductive woman whose power and sexuality lead men to destruction. Gustav Klimt’s Judith I presents a woman with an uncontrollable force. Another archetype is the witch—depicted as a threat to social order, the outcast of culture. Francisco Goya’s Witches’ Sabbath illustrates demonic gatherings, reflecting fears of female independence and mystery. Salome, portrayed in Caravaggio’s and Gustave Moreau’s Salome with the Head of John the Baptist, became an icon of seductive female power, merging beauty with destruction. Edvard Munch’s Vampire similarly depicts a woman as a demonic force, draining a man’s energy.

Such portrayals reflect deep-seated societal fears surrounding female independence, sexuality, and authority. In patriarchal societies, women who defied conventions were often demonized—as temptresses, witches, or femmes fatales. These images were not only meant to provoke fascination but also to serve as warnings: a woman who possesses power and control over her own body and fate could become a threat to the established order.

Over time, however, the concept of woman as a danger has been reinterpreted—shifting from demonic force to a symbol of emancipation and defiance against constraints. Contemporary art frequently challenges earlier narratives, portraying women not as destructive forces but as individuals reclaiming control over their image and story. This process of redefinition highlights the changing societal expectations of women and their evolving role in visual culture.

From Passive Muses to Active Heroines and Creators

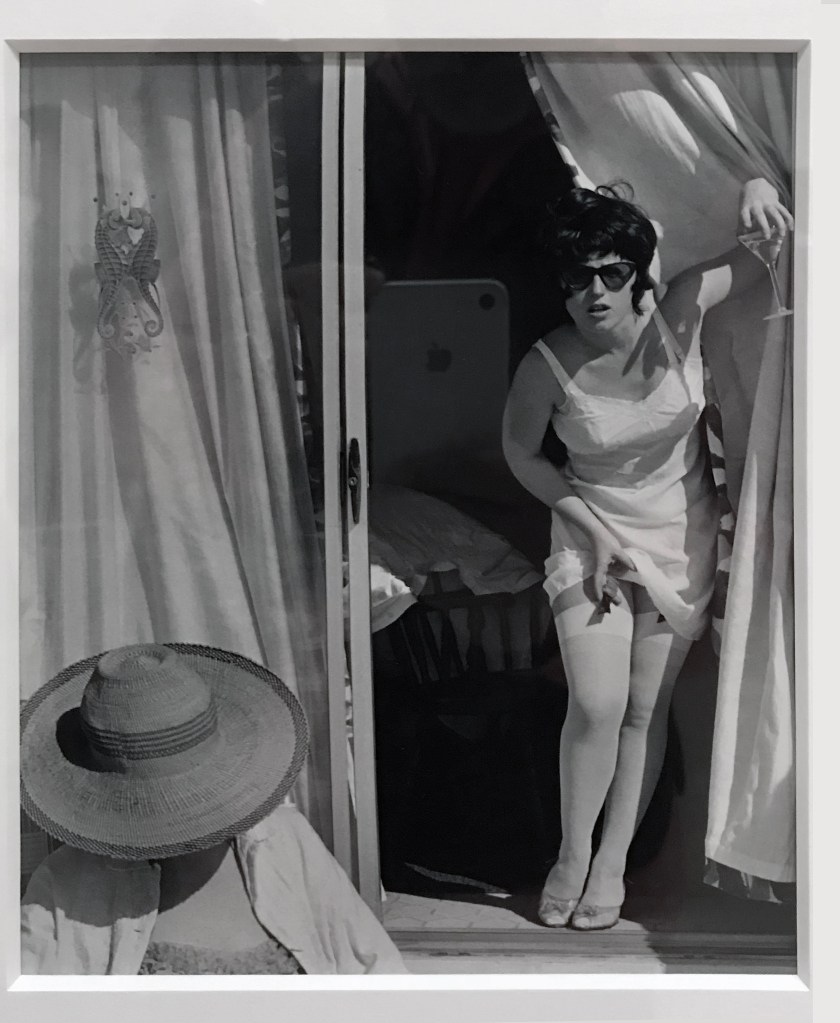

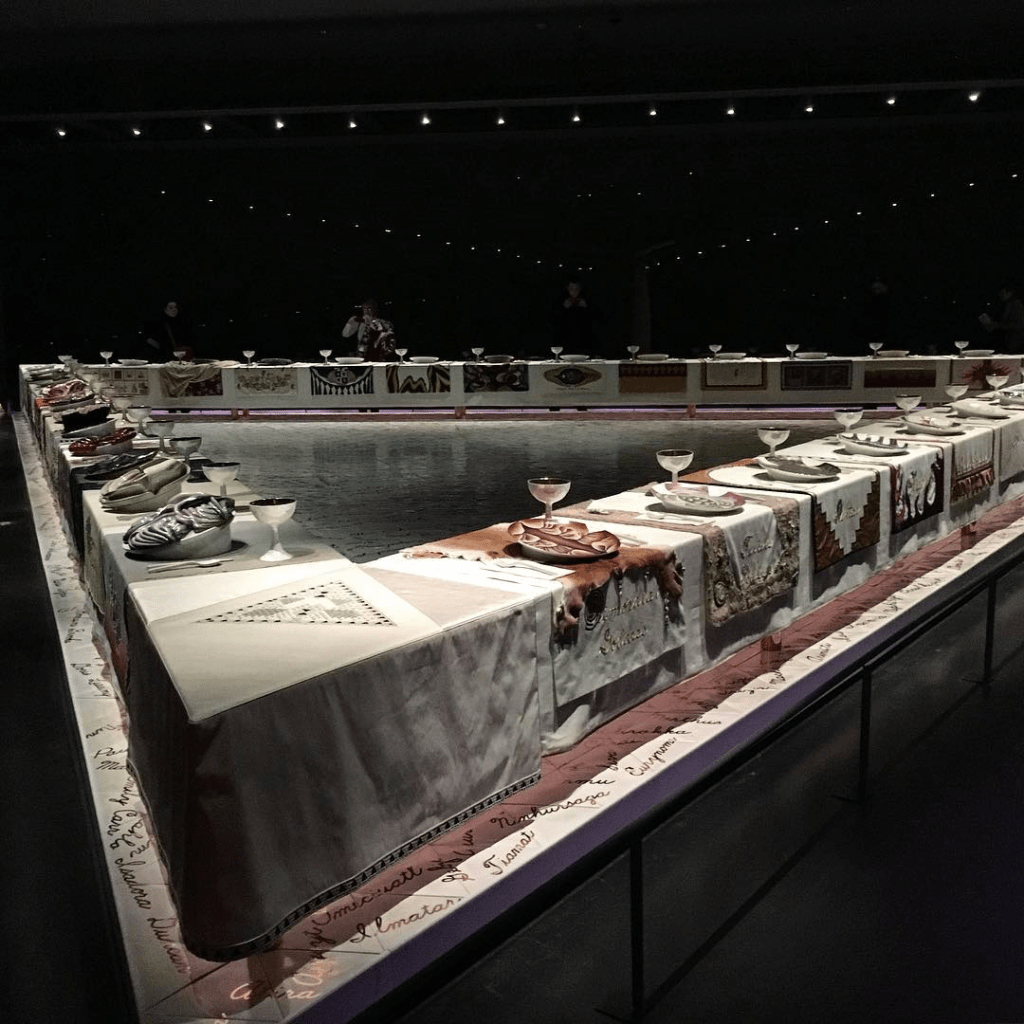

As the 20th century progressed, traditional archetypes began to break down. In modern art, women are depicted not just as objects but as subjects—creators, revolutionaries, heroines of their own stories. Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits, Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills, and Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party reinterpret women’s historical roles in art, shifting them from passive objects of desire to active participants in shaping cultural narratives.

With the growing emancipation of women, their status in society changed, and so did their representation in art. Women began to take control of their own images, deconstructing established norms and creating works on their own terms. Their art often draws from personal experiences but also addresses broader social issues—from women’s rights to resistance against patriarchy and stereotypes. They are no longer merely passive inspirations for male artists but active shapers of new aesthetics and narratives.

At the same time, their role in art is not limited to feminist themes—women artists experiment with form, style, and content, redefining what was traditionally considered “women’s art.” Thus, they are no longer just icons or archetypes but active participants in cultural narratives that they themselves create, transitioning from passive muses to conscious authors of their own stories.

The Evolution of Femininity in Art

The depiction of femininity in art has undergone a long and complex transformation—from passive muses, through idealized beauties, to women demonized as threats to social order. However, the key moment in this evolution was the shift from object to subject—from women depicted in art to women creating art. Contemporary female artists have not only reclaimed their space in the art world but have also actively shaped it, redefining the boundaries of what can be an artistic theme, narrative, and message.

Thanks to the courage of creators who, across different eras, broke conventions and fought for a place in the artistic world, women today can freely explore their identities, experiences, and emotions. Art has become a space for dialogue and a struggle for equality, as well as a means of reclaiming a history that has long silenced their voices. The work of contemporary female artists often serves as a manifesto of emancipation, while the female body—so long controlled by societal norms and beauty standards—is now an artistic expression, a tool of rebellion, and a symbol of strength.

Women’s role in art is no longer limited to inspiration or symbolism—they create, organize, curate, run galleries and museums, influence artistic movements, and define new spaces for creative expression. Art history, long written from a male perspective, is slowly changing, recognizing the contributions and influence of female creators on global cultural heritage.

Ultimately, art—one of the most powerful tools for expressing human sensitivity and awareness—becomes a space where women can tell their own stories anew—without restrictions, without censorship, without imposed roles. Today’s female artists continue the long tradition of their predecessors while simultaneously shaping their own vision of the world—one in which women are no longer just myths, icons, or threats but full-fledged participants and creators of culture. In this way, art not only documents the changing roles of women but also serves as a tool for their emancipation, giving voice to those who were silenced for centuries.

Leave a comment