The “canon of beauty” represents a set of aesthetic standards that dictate which physical attributes are considered attractive and desirable within a specific temporal and spatial context. This canon encompasses particular determinants of beauty, including body shape, proportions, facial features, hairstyles, and even postures and facial expressions. It serves not only as a reflection of aesthetic preferences but also embodies the social values and aspirations that evolve alongside historical periods, cultural contexts, and political and religious influences.

The canon of beauty is intricately linked to the culture of a distinct epoch, functioning as a cultural mirror that reveals the values cherished at a given moment and the prescribed social norms. For example, in ancient Greece, the canon of beauty emphasized harmony and proportions of the human form, embodying Greek ideals of balance and perfection. During the Renaissance, a period marked by a renewed fascination with the human body and nature, beauty was the embodiment of sensual, rounded forms representing fertility and sensuality.

The media and various platforms have also significantly influenced the canon of beauty. A noteworthy example is the 20th century, during which fashion, cinema, and later television and the Internet began to profoundly shape social perceptions of attractiveness. As such, canons of beauty not only indicate aesthetic values but also serve as a medium for expressing aspirations, social belonging, and hierarchical status.

Classical representations of feminine allure, such as the Greek sculpture of Aphrodite and Renaissance portraits of Venus, elevated the female form as a representation of vitality, well-being, and fertility. These ideals have been repeatedly solidified and have significantly influenced society’s perception of beauty over the centuries. Notable examples include various interpretations of Venus, such as the famous “Venus de Milo” and Botticelli’s “Birth of Venus,” which established the archetype of youth and physical perfection.

In this context, Jago’s sculpture “Venus” emerges as a contemporary extension of the traditional canon, challenging the historical perspective of the idealized female form. In contrast to classical portraits, Jago presents a woman whose body lacks smoothness and perfection. Instead, the sculpture celebrates authentic signs of aging, highlighting wrinkles, sagging skin, and other life experiences that embody history, wisdom, and maturity.

This interpretation of beauty is not immediately visible, as it transcends conventional aesthetic norms. While classical standards revered youth, Jago’s sculpture pays homage to maturity, making its aesthetic contribution valuable in itself. Consequently, Jago’s “Venus” advocates for a redefinition of beauty and an expansion of the canon to include elements that have previously been marginalized or overlooked—such as authenticity, transience, and the natural beauty associated with the aging process.

Thus, this sculpture serves not only as a work of art but also as a social statement. Jago illustrates that beauty encompasses not only the visage of youth but also the accumulation of life experiences etched in a more mature face. “What does it mean for a woman to be Venus? If a woman is Venus, she is so forever”—Jago. Therefore, the sculpture symbolizes resistance to contemporary aesthetic standards that often exalt youth and strive to conceal the inevitable signs of aging.

The Canon of Beauty in Antiquity

It is essential to acknowledge initial reflections on the canon as a fluid construct that has continuously been intricately linked to the cultural and ethical frameworks of the period in question. Considering that the canon of beauty encompassed the key attributes of the ideal in a given epoch, it consequently reflected concepts of harmony, perfection, and divine order in ancient times. Divergent interpretations in Egypt, Greece, and Rome made the beauty of the female form a medium for expressing an idealized cosmic order.

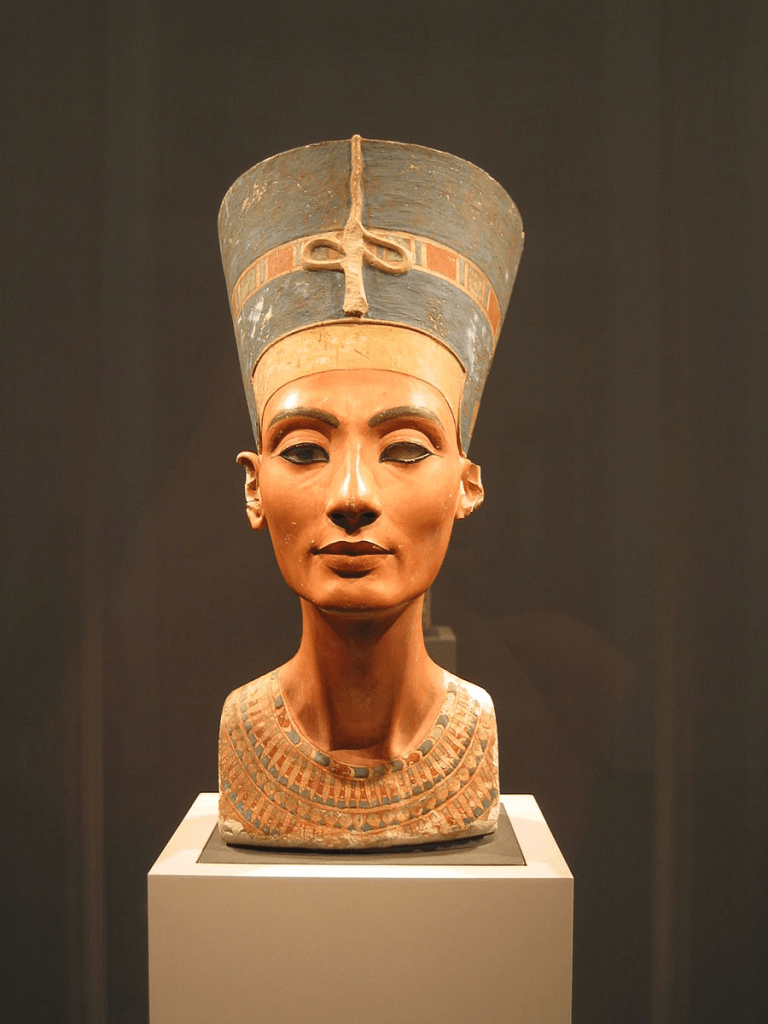

Ancient Egypt – The Canon of Harmony and Perfection

In the artistic expressions of ancient Egypt, the canon of beauty was based on harmony, proportionality, and idealization of form. Representations of Egyptian women depicted their silhouettes in serene, graceful postures, often characterized by impeccably smooth skin, slender waists, and elongated limbs. The bodily form was meant to embody the tranquil rhythm and order that permeated both the cosmos and the religious philosophies of the Egyptians. Egyptian beauty standards, which included slender figures and ideally proportioned faces, were widely standardized, facilitating their replication in various artistic media such as painting and sculpture.

Portraits of women were idealized to symbolize youth and vitality, attributes perceived as emblems of strength and elegance. These principles were intricately linked to beliefs surrounding eternal life, as the Egyptians believed that the soul required a corporeal form for eternity. Consequently, the body was imagined in a symmetrical and timeless manner, devoid of any signs of aging or suffering, and thus meant to signify eternal order.

Greece and Rome — Idealization and the Cult of Symmetry

In ancient Greece, the canon of beauty was cultivated around the principle of kalokagathia—a union of physical charm with moral virtue. The Greek perspective on bodily aesthetics was significantly more dynamic than that of the Egyptians: sculptures portrayed feminine forms in naturalistic, and sometimes overtly sensual, postures, with meticulous attention to anatomical precision. It was commonly believed that both male and female bodies should exhibit perfect proportions, and bodily beauty was regarded in Greece as a close reflection of divinity. Illustrative examples of such representations can be observed in sculptures such as Aphrodite of Cnidus, the first realistic portrayal of a full-scale naked woman, and Venus de Milo, which illustrates classical femininity in a harmonious pose.

The veneration of youth and physical perfection persisted in ancient Rome, though with a greater emphasis on realistic portraits compared to the Greeks. Sculptures from this era reveal figures with pronounced facial features, yet the idealization of youth and vigor remained prevalent. The representation of beauty through symmetry, clear lines, and proportions established a lasting paradigm that has influenced Western ideals of beauty for centuries.

Analysis — Youth and Physical Perfection as Immutable Patterns

In this way, the ancient civilizations of Egypt, Greece, and Rome formulated canons of beauty rooted in youth and idealization of the body, which served as archetypes of physical charm and symbolic manifestations of social and cosmic order. Portraits of youthful and beautifully shaped female bodies expressed a deep admiration for human physicality and its harmonious perfection, making them not only artistic creations but also fundamental elements of aesthetics for millennia to come.

The Middle Ages and Renaissance: Spiritual and Bodily Beauty

As the Roman Empire declined, significant social and religious transformations changed the cultural perception of the human body and ideals of beauty. The subsequent period, known as the Middle Ages, introduced a fundamentally different conception of corporeality and charm—instead of celebrating physical appearance, there was an emphasis on restraint and spirituality, profoundly influencing the beauty ideals of that time.

Middle Ages – Restraint, Modesty, and Spirituality as Ideals of Beauty

In the Middle Ages, physical attractiveness was no longer perceived as the ultimate goal; instead, spiritual values took precedence. The significant influence of Christianity on culture and art led to the exaltation of modesty, humility, and restraint. The female form, once portrayed as perfect and sensual, transformed into a representation of something that should be concealed and regulated to avoid inciting sinful desires. In medieval artistry, portraits of women often featured closed, serene postures and garments that enveloped the body, designed to emphasize their virtues.

The ideal medieval woman was expected to embody holiness and spiritual devotion, with beauty standards rooted in subtle attributes such as a delicate, almost ethereal aesthetic, a fair complexion, and a tranquil gaze. The expression was crafted to convey serenity, often reflecting suffering and renunciation, embodying the religious conception of virtue. Corporeality was seen as a potential source of sin, leading to the suppression of physical beauty and a shift of focus to spiritual ideals.

Renaissance – The Revival of Corporeality, Sensuality, and Ancient Ideals

Around the 15th century, with the advent of the Renaissance, there was a renewed appreciation for corporeality and the aesthetics of the female form, drawing inspiration from classical antiquity. The Renaissance represented a revival of interest in the science, art, and literature of ancient Greece and Rome, resulting in a new perspective on the body as an expression of beauty and perfection. The beauty standards of this period began to favor fuller, more sensual figures, symbolizing fertility and vitality. The female body was depicted as elegant, soft, and sensual, and physicality was once again recognized as an essential aspect of existence.

The epitome of this revival of sensual beauty is the famous painting by Sandro Botticelli, “The Birth of Venus,” which illustrates the goddess of love in all her bodily glory. The Renaissance Venus embodies not only physical beauty but also the essence of femininity. Unlike medieval representations, Renaissance artworks emphasized the naturalness and curves of the body, symbolizing the richness of feminine nature and inner depth.

Contextualization – Evolving Canons of Beauty in Relation to Corporeal and Spiritual Perspectives

The contrasting beauty standards of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance illustrate how different approaches to corporeality and spirituality influenced ideals of beauty. In the Middle Ages, religious focus on modesty, celibacy, and spiritual principles marginalized corporeal beauty in favor of subtle, virtuous characteristics. Conversely, during the Renaissance, the cultural resurgence of connections with antiquity allowed the body to regain its aesthetic significance, and natural beauty was celebrated once more. The interplay between corporeal and spiritual values remained a variable balance, defining the boundaries of beauty standards for each era. These changes emphasize the profound impact of culture on our perception of beauty, adapting it to the prevailing social values and beliefs.

Baroque and Classicism: Opulence vs. Rationalism

The Renaissance developed its appreciation for corporeality, sensuality, and the revival of classical ideals of beauty, evolving into a more complex form during the Baroque period, before returning to a more restrained approach in Classicism. While the Renaissance heralded the celebration of sensual feminine form, the Baroque period initiated this celebration, showcasing the abundance and sensuality of the body in a grand and theatrical manner, while Classicism restored the principles of ancient balance and harmony.

Baroque – Abundance, Corporeality, and the Drama of Form

In the Baroque era, beauty standards transitioned from the harmonious ideals of the Renaissance to a celebration of abundance, richness of form, and the “drama” inherent in corporeality. The aesthetic values of this period favored full, rounded shapes that embodied wealth, fertility, and splendor. Baroque representations of the female figure are vividly illustrated in the works of Peter Paul Rubens, who portrayed women with voluptuous and sensual forms characterized by wide hips, full thighs, and large bosoms. Artworks from this era depicted the body as a source of energy, dynamically engaged in space—a feature that aimed to evoke emotional responses and a sense of movement in Baroque art.

Striking portrayals of the female form served as a medium of expression, showcasing richness and sensuality. Female beauty was not just “present” in art; it occupied a central place, captivating the viewer’s gaze and eliciting emotional reactions that embodied the theatrical aesthetics of the Baroque. During this period, the female body became a powerful symbol of vitality, eroticism, and expression, and art sought to emphasize these traits in an almost exaggerated manner.

Classicism – Harmony, Simplicity, and Restraint

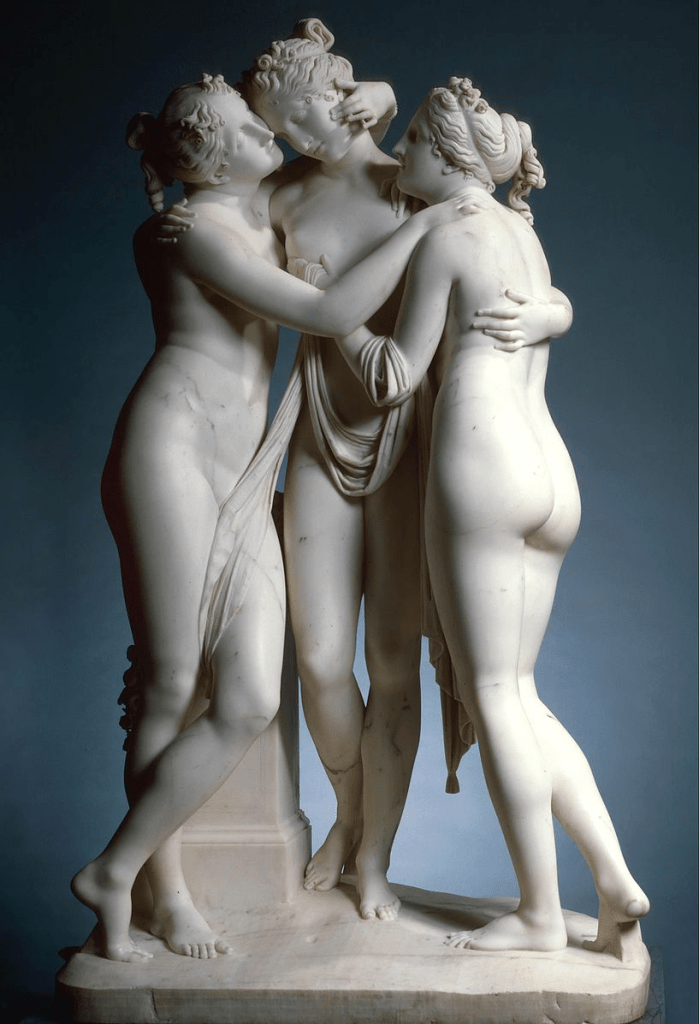

Following the fervent expression of the Baroque, Classicism restored ideals of beauty reflecting ancient harmony and rationality. This period brought a renewed appreciation for simplicity, proportionality, and clear contours of the body, directly relating to ancient paradigms, such as the ideal of symmetry. The female form was represented in a more subdued manner, emphasizing elegance over abundance. Representations aimed for balance, where beauty was conceived as a synthesis of physical proportionality and spiritual harmony.

Examples of the classical view of beauty are visible in the sculptures of Antonio Canova, which depict women with slender, graceful silhouettes, subtly highlighting anatomical details. In contrast to the Baroque, Classicism conceptualized beauty as an inwardly serene and universal trait meant to reflect the values of rationalism, order, and tranquility characteristic of that epoch.

The Contrast Between Baroque and Classicism – Different Approaches to the Female Body

The dichotomy between the expressive, Baroque standard of beauty and the restrained Classicism perfectly illustrates the evolution of ideals of beauty concerning corporeality and aesthetic form. The Baroque celebrated emotionality, richness, and sensuality, where ample female forms became symbols of vitality and eroticism. Conversely, Classicism returned to a more understated concept of beauty, drawing from the ancient ideal of balance, symbolizing the pacification of emotions and an emphasis on spiritual equilibrium.

XIX and XX Centuries: New Media, New Canons

Classicism and Baroque represent divergent methodologies regarding corporeality and aesthetics—ranging from the dramatic abundance of forms to the elegance of restrained harmony. However, the 19th century witnessed the emergence of powerful cultural movements that fundamentally changed our perception of the body and notions of beauty. The evolution of Romanticism, along with the advent of photography and cinema, combined with the influence of women’s emancipation, facilitated the emergence of new paradigms of beauty that began to gain significance at the turn of the century.

The 19th Century—Romantic Expression of Emotion and Individualism

In the context of Romanticism, the female body was presented in a deeply emotional and individualistic manner, resonating with the characteristics of the era and reflecting the spiritual and emotional essence of femininity. Artistic expressions of Romanticism often showcased female silhouettes characterized by delicate contours, infused with a sense of unease or melancholy, with beauty manifesting through subtle complexities and often ethereal presence. This concept of beauty was meant to be personal and distinctive, aligned with the unique character of the individual, standing in stark contrast to the universal standards of harmony and restraint prevailing in Classicism.

The Turn of the 19th and 20th Centuries—The Influence of New Media on the Canon of Beauty

As the 19th century came to a close, innovative media such as photography and film fundamentally transformed perceptions of beauty. For the first time, human bodies and faces were captured en masse, leading to a tangible, everyday aesthetic of beauty. Greater emphasis was placed on outward appearance in public life, with images of models and actresses establishing a new standard of beauty. Particularly in the 1920s, a trend towards a slender silhouette prevailed, largely reflecting a new ideal of femininity that was more dynamic, liberated, and adaptable to change. The concept of the body became increasingly plastic, adjusting to shifting trends.

This era also marked the beginning of a fashion revolution, coinciding with the growing influence of popular culture. Fashion began not only to dictate concepts of the ideal body but also to reflect social transformations, such as the advancement of women’s rights. Over time, the body evolved beyond mere aesthetic representation to become a symbol of social change—women gradually abandoned corsets, adopted shorter dresses, and the image of women became more active and independent.

Contemporary and Alternative Canons—Diversity and Authenticity

In the second half of the 20th century and the early 21st century, the canon of beauty increasingly shaped by global media and strong social movements emerged. Initially, an athletic and slender silhouette was celebrated, resonating with the pace of modern life, while media—including television, magazines, and the internet—propagating the exceptional ideal of slimness. However, as time went on, alternative beauty standards began to emerge, challenging existing paradigms. Social movements, such as “body positivity,” redefined beauty by emphasizing the importance of authenticity and diversity.

In contemporary society, the canon of beauty is more inclusive than ever before. Through campaigns promoting body acceptance and inclusion, countless shapes, skin tones, sizes, and distinctive features are celebrated. The internet and social media have facilitated the dissemination of concepts related to authenticity and self-expression, and contemporary movements emphasize values such as mental health, self-acceptance, and respect for individual differences.

Consequently, the contemporary canon of beauty differs from one-dimensional standards, transforming into more accessible and flexible frameworks. It is evident how contemporary media and social movements are reshaping standards of beauty, supporting diversity and authenticity in stark contrast to historical paradigms that adhered to rigid and restrictive norms.

Contemporary Society and the Alternative Canon: Diversity and Authenticity

Contemporary social movements and media have disrupted traditional uniform standards of beauty, promoting diversity and authenticity. Initiatives such as “body positivity” have supported a wide range of body types, marking a crucial advancement in the fight against restrictive norms. Nevertheless, despite the growing acceptance of various body shapes and individual aesthetic features, a deeply rooted cultural fixation on youth and ideal proportions persists. In this context, Jago’s work “Venus” serves not only as an artistic commentary but also as a significant contribution to the redefinition of beauty.

Jago’s “Venus”—The Beauty of Transience and Maturity

The sculpture “Venus” by Italian artist Jago boldly challenges prevailing standards of beauty by depicting an older woman whose body reflects the passage of time. “Venus” stands out as a distinctive piece because it undermines the conventional image of Venus as a youthful, idealized goddess embodying physical perfection. Instead, the artist chooses a mature female form adorned with the natural markers of aging—wrinkles, sagging skin, and signs of time—which are elevated as integral elements of her beauty.

Jago’s “Venus” responds to contemporary standards of beauty that, while increasingly inclusive, still rarely celebrate the aesthetics of aging. This sculpture, depicting the body of a mature woman with deep respect and artistic sensitivity, conveys to the audience the inevitability of transience, which Jago presents as a value in itself rather than something to be “corrected” or hidden. This perspective is revolutionary, as it avoids imposing an image of beauty based on eternal youth, instead encouraging us to embrace and honor maturity as an equally significant aspect of beauty.

How Does Jago’s “Venus” Comment on Our Obsession with Youth and Physical Perfection?

In an era dominated by social media, where filters and retouching are commonplace, the sculpture “Venus” serves as a significant counterpoint. Jago challenges our fascination with eternal youth and ideals of physical perfection, illustrating that beauty can also reside in transience and maturity, in attributes that reflect authentic existence. “Venus” unequivocally conveys that the body and its physical form are mutable and natural, and that within these transformations lies both aesthetic and emotional depth. This interpretation of beauty fosters a broader perspective, in which body acceptance—at various stages of life—emerges as the ultimate expression of self-acceptance and authenticity.

Why is This Sculpture Groundbreaking for the Contemporary Audience?

Jago’s sculpture “Venus” is groundbreaking because it confronts the viewer with a concept of beauty that encompasses maturity and transience, concepts that are rarely represented in visual culture. In stark contrast to traditional beauty standards that prioritized youth, proportional perfection, and symmetry, “Venus” introduces a fresh aesthetic—emphasizing that beauty can be vibrant and unique even in later stages of life.

This alternative view of female corporeality provides contemporary audiences with new opportunities for interpretation and experience of aesthetics. In times when social media exerts immense pressure to maintain a youthful appearance, Jago’s “Venus” encourages us to reflect on our relationships with our own bodies and to appreciate every phase of our lives, even those that are typically not considered “ideal.” This work symbolizes progress toward acceptance that transcends established beauty norms, nurturing authenticity, diversity, and a comprehensive appreciation of the significance of every stage of life.

Summary of the Evolution of the Canon of Beauty

Over the centuries, the canon of beauty has undergone profound transformation. From the idealized and harmonious forms of ancient Egypt and Greece, through the dramatic and sensual representations of the Baroque, to the balanced idealizations of Classicism, each style reflected the aesthetic and cultural values of its time. Subsequently, Romanticism and modern media introduced innovative, emotionally rich, and diverse interpretations of beauty that gained popularity in the 19th and 20th centuries. Ultimately, in the 21st century, movements like “body positivity” have led to the perception of beauty through the lens of diversity and authenticity, highlighting changes in our understanding and acceptance of the body at various stages of life.

Are We on the Path to Accepting True Diversity?

Looking to the future, it seems that we are moving towards the acceptance of true diversity in the canon of beauty, despite the need for further progress. On one hand, the growing acceptance of diverse body shapes, skin tones, and individual characteristics in media is encouraging. Body acceptance movements that challenge traditional paradigms of beauty are gaining momentum, and emerging generations recognize the importance of authenticity and diversity. However, the persistent proliferation of idealized images in media—often reinforced by retouching and filters—poses a challenge to this journey.

Promoting acceptance of all body types, including those that exhibit maturity, wrinkles, and natural features, is crucial in striving for a more inclusive canon of beauty. Jago’s sculpture “Venus” seamlessly fits into this trend, facilitating discussions about aging, a topic often overlooked in conventional media.

Conclusions on the Impact of Works like Jago’s “Venus” on Contemporary Perceptions of Beauty and Self-Acceptance

Works like Jago’s “Venus” significantly shape contemporary perceptions of beauty and self-acceptance. By depicting beauty in a mature form, this sculpture competes with dominant concepts of beauty. In a cultural landscape often focused on youth and perfection, “Venus” emerges as a symbol of transformation, prompting reflection on the essence of self-acceptance and the belief that our bodies can embody beauty regardless of age and appearance.

Jago illustrates that beauty is neither static nor limited to restrictive definitions; it is a dynamic concept that evolves with us and our experiences. Such works inspire us to broaden our perspectives and embrace a more inclusive definition of beauty that celebrates diversity, authenticity, and the intrinsic value of every stage of life. Ultimately, their impact extends beyond the realm of art into the fabric of social culture, potentially catalyzing lasting changes in how we perceive one another and how we respect diversity in its countless forms. And considering that Venus represents femininity, let us celebrate this beauty in all its manifestations.

Leave a comment