“We will be understood in 100 years”, Lazar Khidekel once stated, a sentiment that resonates deeply in our current era of artistic expression. This aligns with the theme of the 58th Venice Biennale in 2019, titled “May You Live in Interesting Times,” which emphasizes the cyclical relationship between art and societal upheaval. A century ago, the “Roaring Twenties” emerged as a transformative period in Europe, marked by recovery from World War I, political instability, and a cultural renaissance. Today, we face a similar backdrop of global turmoil, where themes of war, political persecution, and human vulnerability remain ever-present.

Now, we exist in a time that Siegfried Kracauer referred to as a “psychological omnipresent camera“. This concept underscores how modern society witnesses constant observation and documentation of life, with all aspects of existence captured and interpreted through various media. Consequently, the lines between reality and its visual representation become increasingly blurred, creating new opportunities for artistic expression and analysis.

In a world filled with news of conflicts and humanitarian disasters, art once again serves as a crucial tool for understanding and critically examining these tragedies. Artists create dialogues about human suffering, bridging the personal and the social.

Furthermore, as globalization intensifies, issues of cruelty, discrimination, and a lack of empathy toward the “Other” have become more pronounced. These challenges have emerged as central themes in contemporary art, reflecting the complexity of social interactions while highlighting the importance of understanding and compassion. By engaging with these subjects, contemporary artists utilize their creations as platforms for social change, urging society to reflect on its values and relationships with the world around them. Thus, art not only documents reality but also plays an active role in shaping it.

A century ago, Expressionist artists aimed to express their anxieties through their work. Their creations conveyed feelings of despair, inner uncertainty, and a disconnection between the individual and society, with a central focus on human vulnerability amid new political and social challenges. Groups such as “Die Brücke” (The Bridge) and “Der Blaue Reiter” (The Blue Rider) were instrumental in developing this movement.

The artists of “Die Brücke,” including Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fritz Bleyl, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Erich Heckel, drew inspiration from primitivism, post-impressionism, and fauvism, experimenting with various techniques and forms. Their work was infused with social critique, reflecting the revolutionary changes occurring in society.

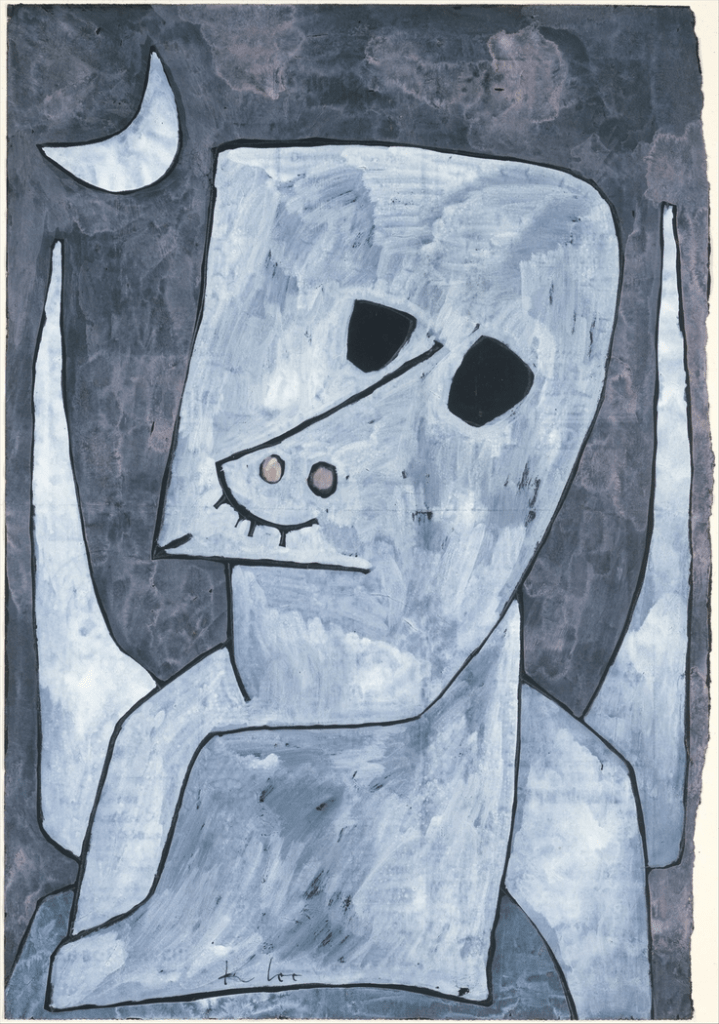

“Der Blaue Reiter,” featuring artists like Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Paul Klee, and Alexej von Jawlensky, concentrated on avant-garde development and abstraction, striving to express inner spiritual experiences and the connection between humanity, nature, and the universe. These movements significantly influenced Expressionism in Europe and the U.S., shaping a new artistic reality that continues to inspire contemporary creators.

Parallel to the Expressionist movement in Germany, modernist trends were emerging in Poland and Ukraine. In 1917-1918, three independent groups formed in Poland: the “Polish Expressionists” (Formists) in Kraków, “Bunt” in Poznań, and “Jung Idysz” in Łódź. Formism, as a movement, combined elements of cubism, futurism, and expressionism, creating a unique synthesis of modernist forms with national and cultural traditions.

One of the most renowned Formists was Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz also known as Witkacy, whose work played a key role in shaping this movement. Witkacy organized numerous exhibitions and became the chief ideologue of the Formists, gathering around him the avant-garde intelligentsia of the interwar period. As the Polish writer Witold Gombrowicz noted: “There were three of us: Witkiewicz, Bruno Schulz, and I — the three musketeers of the Polish avant-garde of the interwar period”.

Kompozycja fantastyczna, 1920, Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie

Just as Expressionism in the 1920s addressed themes of social critique, war trauma, and alienation, so does contemporary Expressionism, as a continuation of these ideas, focus on the emotional and political landscape. For example, Kateryna Lysovenko, along with many other contemporary artists, continues the tradition of Expressionists, using painting to express deep personal and collective traumas, reflecting on utopias tinged with “Neue Sachlichkeit” (New Objectivity). Sana Shahmuradova Tanska, in imitation of past Expressionists with an emphasis on magical realism and the ritual of retraumatization after experiencing war in Ukraine, said in an interview: “I just started to turn to some very clear direct images, such as the photographs of war crimes. I realize that no matter how hard I try to convey these, I still get some very universal images”. This approach, expressing trauma through visual images, demonstrates that the methods of Expressionism remain relevant in contemporary art.

Let’s also consider several Polish artists who can be linked to this movement: Paweł Śliwiński and Konrad Żukowski. Unfortunately, no contemporary Polish artist can be fully classified as Expressionist, but the influence of the movement is evident. For instance, Paweł Śliwiński associates himself with the “tired of reality” movement, which leans toward the poetics of surrealism. Meanwhile, Konrad Żukowski merges Expressionism with magical realism, frequently incorporating the image of the priest.

Despite the close connections between Polish and Russian artists, Expressionism as an art movement left no significant mark on the territory between them — namely Belarus. However, many artists born in Belarus who found themselves in Paris became part of the École de Paris (School of Paris), where their work can be classified as part of this style. Such artists include Marc Chagall, Chaim Soutine, Ossip Zadkine, Michel Kikoine, and Faïbich-Schraga Zarfin. Interestingly, the trend of collecting works by École de Paris artists was observed in Poland between the 1950s and 1970s, driven by various factors, including cultural and political changes in the country after World War II.

In Belarus itself, Expressionism was represented by only a few figures. One of them was Roman Semashkevich, who, like many cultural figures of his time, was executed in 1937. His works show emotional intensity and experimental approaches to form and colour. Another was Vladimir Kudrevich, who leaned more toward Impressionism than Fauvism or Cubism.

As of 2024, some prominent representatives of Expressionism include Margarita Dyushko, who explores themes of the horrors of everyday life in a Neue Sachlichkeit manner, fully emulating the Expressionists of the 20th century. Irina Kotova, widely known in certain circles, expresses the influence of Expressionism and primitivism in her work. Roman Kaminski, like Konrad Żukowski, blends Expressionism with magical realism. Lastly, there is Anastasia Rydlevskaya, who discusses fears through naïve imagery and, like the Expressionists of the past, uses frank, “direct” images of war and violence to emphasize the impossibility of conveying the full depth of human tragedy.

Thus, Expressionism, as an artistic movement that began more than 100 years ago, continues to influence art today. Its methods and themes remain relevant, as humanity continues to face the same challenges: war trauma, alienation, and the search for meaning in a chaotic world.

Literature sources:

• https://culture.pl/ru/artist/stanislav-ignaciy-vitkevich-vitkaciy

• Kolekcja Fundacji Sztuki Polskiej ING 2000-2020, p. 240

• https://www.culturedmag.com/article/2023/06/28/ukraine-artist-sana-shahmuradova-tanska

Sources of photographs:

- E. Nolde, Slovenians,1911 – private collection. Archive of Illustrations WN PWN SA © Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN

- Paul Klee, Angel Applicant, 1939, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/483181

- Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Self-Portrait with Cat, 1920,https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/304414?position=0

- Kateryna Lysovenko, Dream about saved lives, 2024, https://www.instagram.com/p/C71nY4KthH-/?igsh=Nmg1emdmOWRwczE4

- Sana Shahmuradova Tanska, Scars Came Before Me, from the I Thought They Were Flowers series, 2024,https://www.sanashahmuradovatanska.org/works

- Paweł Śliwiński, Waiter, 2020, https://www.instagram.com/p/CxFmGpIofp7/

- Konrad Żukowski, Untitled, 2024, https://www.instagram.com/p/C3zy7eFIU7q/?igsh=N3czd2ozcnF0c2N4

- Margarita Dyushko, The skill of happiness, 2023, https://www.instagram.com/p/CyOGZb1oDGw/?img_index=1

- Irina Kotova, Hush, 2022 https://www.instagram.com/p/CnPRK3tIqas/?img_index=1

- Roman Kaminski, magic garden, 2024 Раман Каминский | «magic garden» 100×100 cm Oil/canvas 2024 Ucan buy this painting #art #artist #painting #oilpainting #artwork #artlover #artcollector… | Instagram

- Anastasia Rydlevskaya, MANIA, 2024, Anastasia Rydlevskaya | MANIA oil on canvas 120*90 cm 2024#arydlevskaya_oil #art | Instagram

Leave a comment