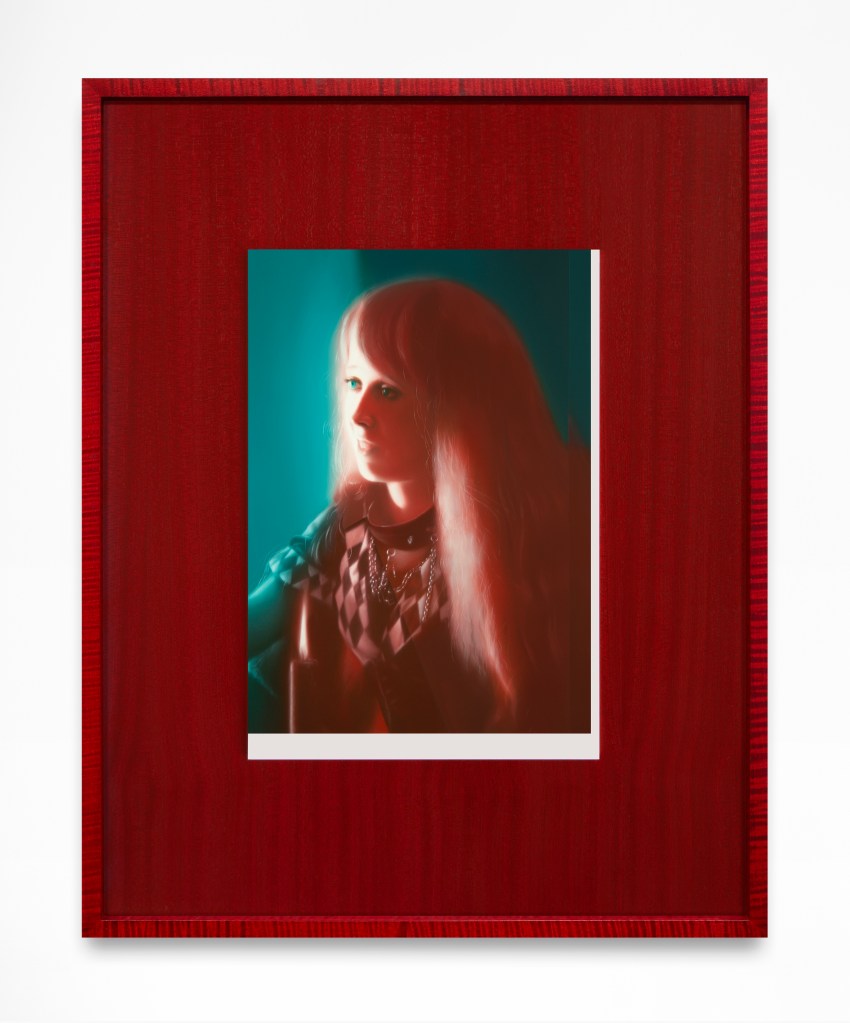

Andrew Sendor is a visual artist who lives and works in New York. Sendor is most recognized for his extraordinary facility in representational painting that serves to illuminate his ongoing engagement with the power of the imagination. The artist introduces us to fictional characters in storylines whose genesis derives from a unique creative process: Sendor scripts, produces, directs, and documents performances recounting the life and times of his eccentric cast.

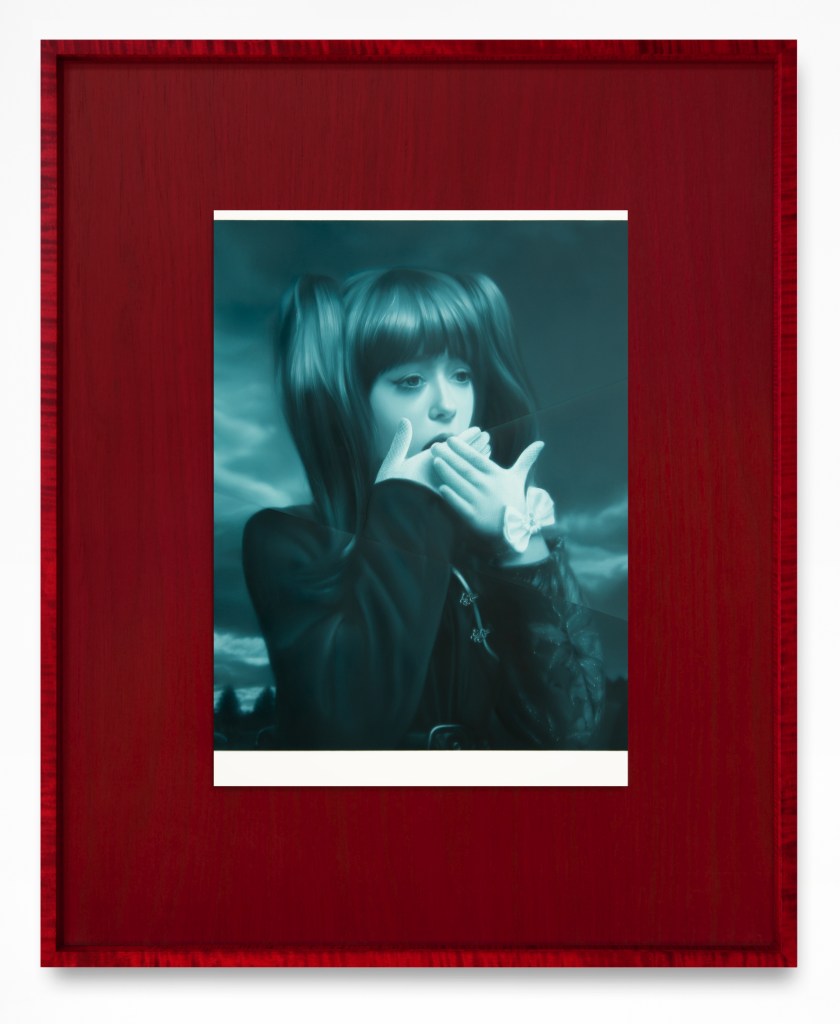

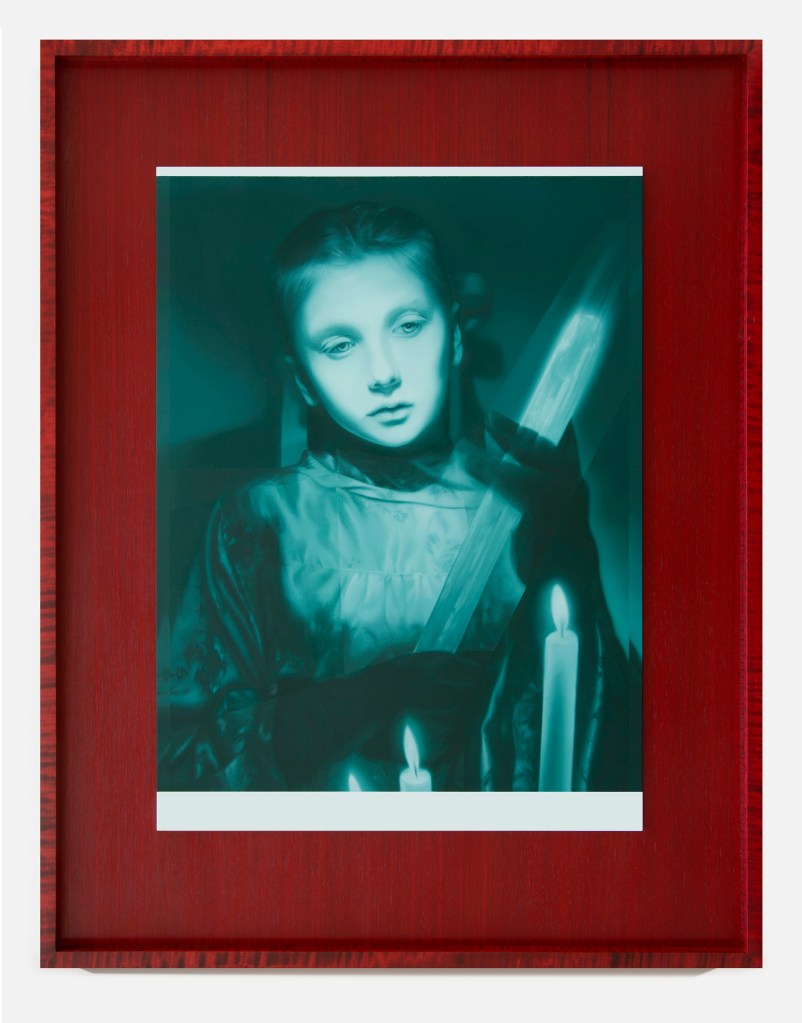

Representing scenes from these psychologically charged, hallucinatory narratives, each meticulously rendered artwork surveys the materiality of images and the interrelated history of photorealism and evolution of photography. Sendor builds monochromatic compositions using acute pictorial focus along with disrupted visual motifs, and situates the works in artist’s frames whose physicality elevates the painted imagery — and which together comprise an idiosyncratic language of painting.

1. Can you share details about your current solo exhibition in Los Angeles at Make Room Gallery?

My current solo exhibition titled Salome & Solvej, Apollo & Farne represents the culmination of one year’s journey into a newly conceived world, captured through a series of artworks that probe the intersections of narrative fiction and the language of painting.

Featured are paintings presented within artist frames, as well as works situated on custom-built wall shelves and pedestals— all within an immersive, site-specific installation. An audio narration streams from strategically positioned speakers, guiding the viewer through key moments within the overarching narrative. This auditory component fosters a multi-sensory experience — replete with content that extends the mystery inherent in the painted imagery. The design of the installation itself is a deliberate effort to poetically replicate the physical sensations and environments found within the narrative. From the placement of the paintings to colors selected for the carpets and painted walls, every element is intended to evoke and enhance the psychological and emotional dimensions of the fictive world.

The narrative upon which the exhibition is built centers on a coming-of-age story featuring Salome, a child prodigy ballet dancer who is thrust into chaos after witnessing a violent confrontation involving her criminal father. Taken in by her loving aunt, Jensyne, in rural Denmark, Salome is given a treehouse — functioning as a sacred space for her trauma recovery. Accepted into a local ballet academy, Salome forges deep bonds with fellow students Solvej, Farne, and Apollo. Disillusioned with the academy’s strict environment, the four friends impulsively decide to run away, embarking on a cycling journey of self-discovery and independence. As they navigate the complexities of the world on their own, they encounter a series of life-changing experiences that challenge their beliefs and illuminate their search for life’s deeper meaning.

2. Your work is known for its intricate storylines and fictional characters. Can you share your process of developing these narratives?

Central to each body of work is a fictional narrative I write that serves as the underlying conceptual framework. The narrative is not merely a backdrop but a dynamic force that propels the creation of the imagery in the paintings. It all begins with “sudden visions” that arise internally. When I envision a character or a group of characters in a specific setting, I start writing about this interior, often fantastical vision. The writing process continues as the narrative organically unfolds, with characters navigating their way through existential adventures — moving from crisis to hope to enlightenment.

3. How do you script, produce, direct, and document the performances that serve as the basis for your paintings?

Once the narrative has taken form, I orchestrate a series of performative events with actors and performance artists who embody the characters within the story. These live performances are more than mere enactments; they are transformative acts that bring the fictional world to life, allowing me to capture its essence in a tangible form.

These performances take place in both indoor and outdoor settings, with the location depending on the content of the narrative. In previous bodies of work, performative events have transpired in rural New Mexico, Northwestern Spain, and upstate New York. Interior scenes are often shot in my Brooklyn studio, which features three rooms, one of which is dedicated to performances and serves as a constantly evolving stage set.

The performances are documented with video and photos, which ultimately function as source material for the painted imagery. The shift from performance to painting involves translating the ephemeral nature of live action into the permanence of painted imagery — a slow process that evolves over time.

4. How do you see the relationship between photorealism and the evolution of photography reflected in your work?

Great question — I am glad you raised this important topic. For the last decade, I’ve been thinking hard about how the distribution and consumption of images occur in today’s society compared to the era before digital photography. If we rewind further, a pivotal moment in the history of image creation is the mid-19th century. As the science of photography evolved from the early Daguerreotypes in the 1840s, critics contrasted painting’s overt subjectivity with the accuracy and speed of the camera. This debate has persisted for decades in various forms. Fast- forward to the 1990s, when digital cameras became more common, prompting a reevaluation of

the strained relationship between painting and photography. Once upon a time, printed photographs were seen as objective reflections of reality—documents captured with the clinical precision of a machine. The great media philosopher Vilém Flusser wrote in the early 1980s, ‘Cameras are programmed purely for the transmission of information,’ and he also argued that their inherent mechanism of distribution characterizes the meaning of the information conveyed in the photograph. This notion prevailed until the analog format was largely replaced by digital. With the rise of graphics-editing software, manipulating photos became quick and accessible, contributing to an environment saturated with images disseminated on tablets, smartphones, and social media. This shift creates a peculiar situation where images feel unstable.

As I create my painted images, I envision them in a transitory state. My painted surfaces are fractured, skewed, asymmetric, and distorted—slipping within their own compositions.

5. Your work often features monochromatic compositions and disrupted visual motifs. What draws you to these particular techniques and themes?

During the winter of 2010, I had the good fortune to see an exhibition titled Jan van Eyck: Grissailles at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museo Nacional in Madrid, Spain, where I was living for one year. Jan van Eyck is a painter I hold in very high regard, along with other early Netherlandish painters, for his remarkably refined skill in pictorial illusionism and his innovative methodologies in oil painting, which set a new path forward for realism. At that time, I was completely enamored by Van Eyck’s grisaille painting titled The Annunciation Diptych (ca. 1433-35). The way Van Eyck transposed light into paint and advanced mimetic representation to the point where a fabric is so convincing it takes on a new character—sliding into a type of alternate reality—captivated me. Achieving these qualities with a reductive palette of black, white, and gray was something I wanted to pursue.

Artist Laurie Simmons once said that she’s always trying to clear away what exists between herself and the subject. I felt that by reducing my palette to black, white, and gray, I could do just that. I continued making paintings in this limited palette for six years before transitioning to blue monochrome, which I continue to explore.

6. Your exhibitions have spanned many prestigious venues worldwide. How do you prepare for a solo exhibition, and what have been some of your most memorable moments?

Since 2015, each of my solo exhibitions has been centered around a single fictional narrative and the characters featured within it. Typically, the early stages revolve around becoming familiar with the story and the psychology of the characters, which leads to the performances and eventual source material for the paintings. Then, I begin to envision how this can be transposed into the form of an exhibition in a public setting.

My work has been exhibited in galleries and museums in North America, Europe, and Asia, and I feel extremely fortunate for numerous memorable moments.

In late 2015, The Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum at MSU mounted a solo exhibition of my work titled Andrew Sendor: Paintings, Drawings, and a Film. The museum, designed by Zaha Hadid, features no right angles within the interior gallery spaces. It was gratifying to see my work situated in such an important public space with exquisite architecture.

On the ground floor, both small and large-scale paintings and works on paper were exhibited. In the museum’s New Media Gallery, my short film titled FENOMENO (2015, HD video,13:44 minutes) was projected at a width of 16 feet in a fully darkened space. It was a productive and inspiring experience working closely with the museum Director, Michael Rush, and curator Caitlín Doherty.

7. In addition to your exhibitions, your works are part of significant public and private collections. How do you feel about your art being included in these collections?

It is a wonderful honor when private collectors and museum directors connect with my work on a deep level and express a desire to make an acquisition. I appreciate everyone who has supported my artistic vision over the years. A couple of highlights include two works on paper being included in the permanent collection of The Morgan Library & Museum in New York, a venerable public institution that is celebrating its 100th anniversary. Featured in their vast collection are Renaissance manuscripts, Old Master drawings and prints, literary and historical manuscripts, and Modern and Contemporary Art. Regarding institutions focused on contemporary art, Hall Art Foundation, MOCA Jacksonville, and The Rubell Museum in Miami, Florida each own several of my works.

8. What are some of the biggest challenges you have faced in your artistic career, and how have you overcome them?

Willem de Kooning once said, “There are no vacations in painting.” I absolutely agree with this; it’s the relentless nature of being an artist that can be challenging. I have discovered that acceptance can offer a path to inner peace.

9. Can you describe your journey as an artist? What inspired you to pursue a career of a visual artist?

I began to take drawing seriously when I was 13 years old, and I remember telling myself that I wanted to make art forever.

Leave a comment