The British Museum, often entangled in debates over its acquisition of artifacts, recently faced a new controversy thanks to the bold actions of Brazilian conceptual artist Ile Sartuzi. Sartuzi, known for his thought-provoking art, replaced a historic British coin with a counterfeit during a visit to the museum, aiming to highlight the institution’s vast collection of foreign artifacts.

The idea came to Sartuzi when he observed a museum volunteer handing out coins for visitors to handle. Artist specifically requested a silver coin from the English Civil War era. Taking advantage of a moment of distraction that the artist forged, he executed the swap, leaving the original coin in the museum’s collection box on his way out.

Sartuzi’s actions, first reported by The Art Newspaper and later detailed in a video created for his master’s degree at Goldsmiths, University of London, have sparked significant discussion. The British Museum expressed its disappointment, noting that the act abused a volunteer-led service designed to help visitors engage with history. They have since indicated their intention to notify the police about the incident.

Amidst this controversy, we sat down with Ilê Sartuzi to delve deeper into his motivations, the message behind his provocative act, and his broader perspective on the ongoing debate about the ownership and ethical stewardship of historical artifacts.

Your work often involves animating objects and infrastructural elements. What inspired you to explore this intersection of technology and theatricality?

Theatricality came slowly growing in the work as I started to notice how the objects were projecting themselves in relation to the viewer. Meaning, theatricality first came as the term is used inside Art History rather than necessarily relating to the dramatic arts. After I became conscious about this – and for a number of other reasons – I created a proper theatrical play with absent actors (without any humans on stage). Technology always came as a tool to get somewhere. I was never interested in technology by itself. It is a mean to get to a certain effect or formal quality. Of course, with the use of more or less technological procedures – and I always insist, oil paint is as much a technology as artificial intelligence – different discussions came to be important for the work. Ideas relating to a speculation of a post-anthropocene scenario, the cyborg or “absence” were significant for those works.

Can you tell us more about your conceptual approach and how you develop the narratives for your installations?

Although much of my work is time-based, I would argue that they don’t follow a traditional narrative. In their movements and choreographies, they tend to repeat actions rather than get somewhere. They never start or they never end, most of the time. It is in this process of performing in the moment – trapped in this loop – that we start to understand the mechanisms and the functioning of each of those systems. As a matter of fact, one thing that could be pointed as a common thread in recent works is that through more or less simple gestures they tend to exhibit the mechanisms that animates these themselves.

Your recent project, Sleight of Hand, at the British Museum is both intriguing and bold. What motivated you to undertake such a daring action, and what do you hope viewers take away from it?

The first time I went to the British Museum was on the 20th of March, 2023. On that day, when I entered Room 68, the money section, I saw a man behind a table showing coins from the collection and telling stories about them. This whole setting and the gestures immediately made me think about street magicians, the tricksters performing the good ol’ “cups and balls” routine. With that image in my head, I knew at that point that I wanted to perform a magic trick and steal the British Museum. Evidently, the whole debate around the contested collection of said museum was in the back of my head. As I developed the concept of the work, it became clear that this simple action is complex and layered and the debate can go to many different directions. The decolonial aspect and the “institutional critique” is one of the most direct things that people read and relate with the work. But there are issues regarding the relation with money, value, circulation; not to mention aspects that are really important for me and relate to my practice: thinking about sleight of hand as a form, misdirection as procedure and stealing as art. The fact that the first image that came to me was relating to these “trickster” figures – The Conjurer painting by Hieronymus Bosch is a good one – also says a bit about where some of the interests were coming from. There is a beauty in the poetics of magic tricks, pickpocketing and similar activities.

How did you prepare for the Sleight of Hand project, and what challenges did you encounter during its execution?

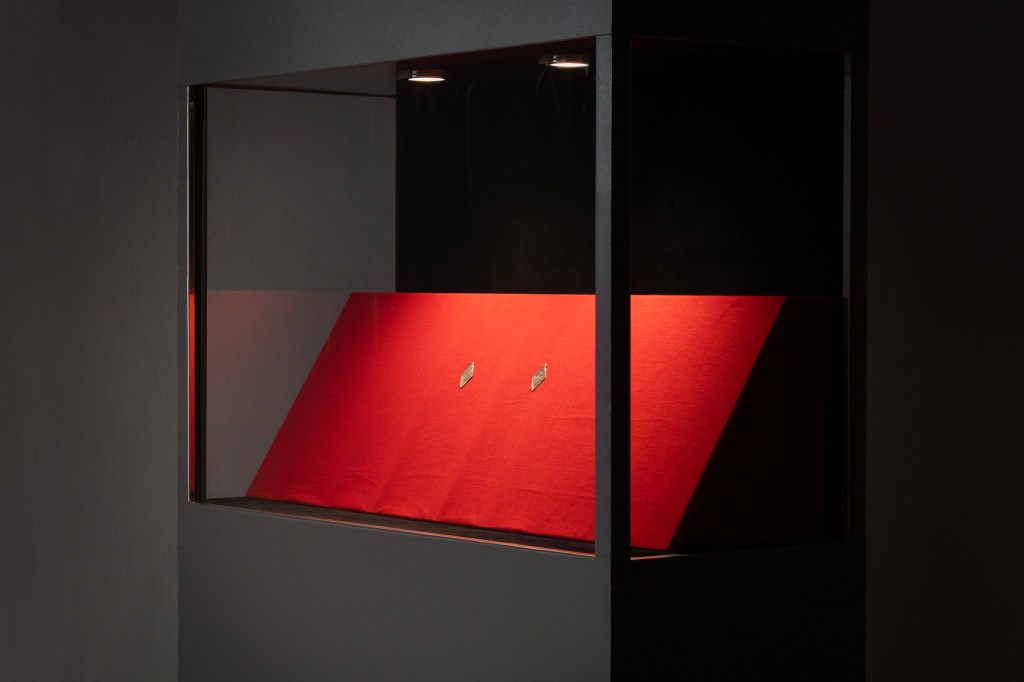

It was more than a year preparing for this project, and I went more than twenty times to the British Museum during this period. The preparation involved different things: from finding information and floorplans from the local council, to understanding security and the way the Museum works. I had to map the timetable of the volunteers because each one would show different coins and I needed to know when my target coin would be available (meaning I spent countless hours inside that museum waiting for the shifts). I had to create a perfect replica of the coin to exchange for the original one. There’s all the conceptual research and writing that comes backing up the project. I discussed with close peers and had legal advice with a specialist lawyer. Writing a script of the action, thinking about how to shoot the documentation, gathering my crew, rehearsing before in a different place with replicas of the furniture of the space so we get a spatial dimension of how to move; it was really a thorough process of preparation for this heist. throughout the whole time I was afraid that they would cancel the program or stop showing the coin at some point, change for different coins or something that would make the plan impossible to go through (this was intensified during the period that the news from the other stealing came and the change of directors of the Museum, I was already working on this).

The use of mechanical movements and repetitive actions in your work often leads to a unique form of storytelling. Can you elaborate on the significance of repetition and the absence of catharsis in your installations?

Repetition is a dramaturgical strategy that can be used in different ways. In art, it has a specific quality because time-based works usually have to repeat themselves during the opening times of the exhibition. In other words, they are trapped in a loop. If we take into consideration this aspect of the loop, this tireless repetition soon starts to sound a bit crazy and brings formal qualities that points to (or comes from) mechanical and industrial movement, or a dumb character, or pointless conversations. Repetition could be an emphasizes on something. An idea that is stuck in someone’s head. For me, Samuel Beckett was one of the best to ever do it and probably the best example is Waiting for Godot. In my exhibitions – that are usually populated with time-based works and a loose sense of narrative – the repetition is choreographed in an orchestration of objects that are performing for no one except for themselves.

Your research involves misdirection and sleight of hand, akin to magic tricks. How do these elements enhance the narrative and conceptual depth of your artworks?

Those procedures, I must say, are things that I’m interested now and I’m still in the process of understanding and unfolding the potential of these tricks into an art practice. I enjoy how unconventional it is to bridge these gestures into the contemporary art world and I’m intrigued to see how these things, as form, can continue to enhance narrative and conceptual depth in the works. A magic routine is, as other theatrical forms, a great way of delivering a story and – this is probably one of its best qualities – manipulating people’s regime of attention and expectation.

With a background in both São Paulo and London, how do the cultural and artistic environments of these cities influence your work?

I’ve always been resistant to directly attach my work to a specific environment. It seems hard to relate my work to what a lot of people imagine is the idea of “Brazilianness”. I always thought that the research was in dialogue with a more complex set of references not delimitated by geographical or political boundaries and that was one of the reasons to explore other places. Of course, these two cities have amazingly vibrant art scenes with its own particularities that inevitably impacts the work, but I would still try to resist pointing to specific elements.

What role do you believe art should play in commenting on and interacting with institutional infrastructures?

This (and all the others) question is quite complex and I’ll try to simplify my answer for the sake of this interview. I do advocate for a certain autonomy of art as defended by Theodor Adorno. Meaning, I believe that the political power of art is in it’s form rather than solely in the contents. Faced with an engagement that is based on a set of established forms – an “accommodation to the world” in order to convey its messages – I’d rather bet on the “shock of the unintelligible”. That is to say, it is common that in order to comment on specific subjects, people have to use a quite direct and clear language/form because the important thing is the message. That is quite the opposite of what I believe is the power of art, exploring form. To go back to Samuel Beckett, thought a reading by the French philosopher Alain Badiou, the author writing about “Worstward Ho!” says that “If there is no adequacy, if the saying is not prescribed by “what is said,” but governed only by saying, then ill saying is the free essence of saying or the affirmation of the prescriptive autonomy of saying.”.

That interpretation resonates in Adorno’s writing, in which this “ill saying” is the resistance though forms that were not previously accepted by the world’s order. The work of art has no final purpose, because it is an end in itself. Some may say that is a position that alienates artistic production, but we must have in mind that “there is no material content, no formal category of an artistic creation, however mysteriously changed and unknown to itself, which did not originated from the empirical reality from which it breaks free.”

It is evident that there is a number of other attitudes outside the artistic field; concrete confrontations that must be carried out as an individual living in a society and thus inevitably responsible for the struggles of the political field. But that also does not mean that “autonomous art” does not have its political impact, quite the opposite: what is at stake is the way we view this engagement, which sometimes simplifies the political spectrum. “Bad politics becomes bad art, and vice versa”.

Not to contradict myself, but I believe that Sleight of Hand, in its complexity, manages to be poignant in both form – and because of that – in the relevant debates that it raises. It is not being verbally direct, after all, it’s only a small gesture. In the simplicity of this gesture, in the form of the sleight of hand, it contains a critical mass to fuel heated discussions around institutional infrastructures.

Can you share any upcoming projects or exhibitions you are excited about?

I’m preparing a solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in São Paulo for 2025 where I’m going to show, among other things, Sleight of Hand for the first time in Brazil. I’m also preparing a new set of works for the show that I’m really excited about.

Lastly, what advice would you give to emerging artists who are interested in blending technology, performance, and traditional art forms?

At some point I understood that the categorization of the practice into these boxes is irrelevant. Although I use all these things, I repudiate the binomials of “Art and Technology” or “Art and Politics” for reasons I expressed before. I would say that the art practice not necessarily have to follow these paths, and you can find interesting things in the grey zones between those limits. I would say that you can be an art nerd interested in specific aspects of drawing in Florentine renaissance and be messing around with a technological and experimental theatre, or stealing a museum. This is kind of ridiculous to say and not really helpful, but there is no recipe for building your body of work. Sometimes you will be doing things that you’re still not sure how they relate directly, but again, you don’t need to understand everything while you’re making.

Leave a comment