Have you ever experienced discomfort in large museums when visitors engage in taking photographs of renowned artworks or disrupt the atmosphere by talking loudly to each other? The desire for tranquility and a sense of respect for the artwork becomes palpable within you. You yearn to observe the piece in silence, allowing yourself to shape your own thoughts and impressions without the influence and interpretations provided in museum guides. Unfortunately, this desired introspective experience remains elusive as the only way to perceive the artwork is through the expansive display of a tablet screen used to capture the image of the nearby graphic.

Certainly, we are familiar with ancient churches where loud speaking is strictly prohibited, and in some cases, even taking photos is not allowed. These sacred temples, although major tourist attractions, maintain a peaceful atmosphere; security guards equipped with noisy walkie-talkies stationed at the entrance carefully regulate the number of visitors to preserve the sanctity of the environment and ensure that our breaths do not diminish the precious air inside. This protocol is particularly evident in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome at the peak of the season. However, as the calendar approaches the transition from November to December, when airfares to Rome drop, and the charming Christmas market in Piazza Navona comes alive, one can experience the basilica in close solitude. It is during these quieter moments that one can truly appreciate the magnificent artwork housed in the basilica, a masterpiece that in itself justifies a visit to the eternal city of Rome.

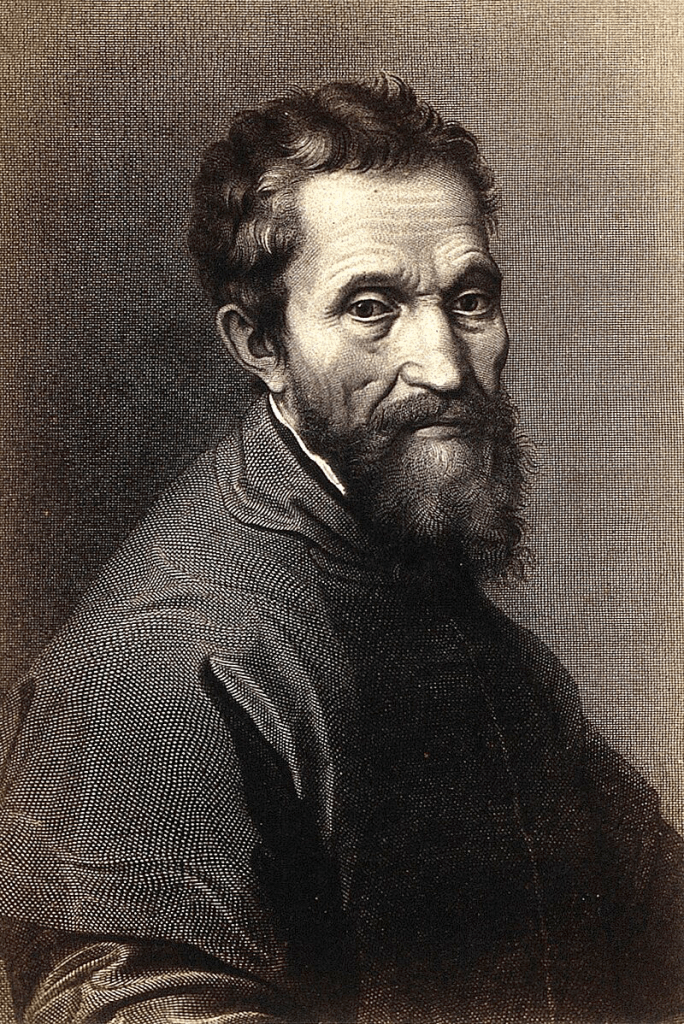

Michelangelo’s masterpiece, Pietà, is a work that evokes a profound sense of peace and contemplation, compelling viewers to pay attention to the Divine. The commission of this famous sculpture, known as the Marble Pietà, depicting the Virgin Mary cradling the lifeless body of Christ, was bestowed upon Michelangelo by the esteemed French Cardinal Jean Bilhères while the artist resided in Rome. This exquisite piece was intended for Santa Petronella and designed to adorn the tomb of the cardinal. Demonstrating unwavering dedication to his craft, Michelangelo personally travelled to the Carrara quarries to hand-select the finest block of marble, fully aware that this work would serve as his pathway to lasting renown in the art world. The arduous process of transporting this massive marble block from Carrara to Rome was a labor-intensive endeavor that lasted nine months, underscoring the meticulous planning and sheer determination that characterized Michelangelo’s approach to his artistic endeavors. This journey from quarry to final destination not only symbolizes the physical labor associated with sculpting a masterpiece but also encapsulates the spiritual and emotional weight imbued in the Pietà, a testament to Michelangelo’s unparalleled skills and artistic vision. Completing this monumental sculpture marked a significant milestone in Michelangelo’s career, cementing his reputation as one of the most revered artists of the Renaissance era and securing his legacy for future generations. Thus, the Pietà stands as a testament to Michelangelo’s genius and serves as a timeless embodiment of beauty, grace, and spiritual contemplation for all who behold its transcendent presence.

In 1496, the narrative begins as follows. It was a period when Michelangelo departed from Florence, a time marked by immense religious and political upheavals. It was an era dominated by the presence of the monk Savonarola, the expulsion of the Medici from the city, and widespread displays of excessive pride and admiration for oneself. First traveled to Bologna and then to Venice, the artist crafted a sculpture of Cupid infused with the essence of ancient art. A wealthy merchant, well-connected in Rome, conceived the idea of creating a fake artwork to deceive antiquity enthusiasts in the Papal City. The statue of Cupid was secretly buried, then artificially aged, and ultimately presented to Cardinal Riario, a renowned connoisseur of ancient artworks. Although the ruse was eventually uncovered during the transaction, Michelangelo’s exceptional talents did not go unnoticed, prompting the cardinal to invite the artist to relocate to Rome.

French Cardinal Jean Bilhères, who served as the ambassador of the King of France to the Apostolic see, had the opportunity to witness the exceptional talent of the young artist Michelangelo. Impressed by his skills, Cardinal Bilhères commissioned him to create a magnificent funerary sculpture group. A formal agreement specifying payment of 450 gold ducats was drawn up, a document that has survived to this day. The agreement stipulated that the sculpture would be the most exquisite marble graphic in Rome, surpassing all others, and that no contemporary artist could execute it more masterfully. Meticulous work on the sculpture lasted over a year, beginning with Michelangelo’s year-long carving process, followed by several months dedicated to polishing the marble to perfection. The masterpiece known as the Pietà was ultimately completed in 1499 when the artist was only 24 years old. Unfortunately, Cardinal Bilhères passed away before the sculpture was finished, and Pope Alexander VI took possession of the Pietà. Initially displayed in Santa Petronella near the cardinal’s tomb, the sculpture was later moved to a chapel in the basilica just before the year 1519. This relocation placed the Pietà in its rightful place at the heart of the basilica, where all visitors to the holy grounds could admire it.

Mary is depicted seated on a large rock representing Calvary, with Jesus taken down from the cross resting on her lap. Her right hand provides support to her son, while her left hand is extended in a gesture of presentation. Mary’s visage is portrayed as youthful, feminine, and serene. Critics during Michelangelo’s time did not accept the youthful appearance of Madonna, but the artist defended his choice, arguing that purity brings a sense of freshness and vitality. A veil gracefully drapes her head, accentuating her beauty, while the intricately sculpted marble allows Mary’s face to stand out against the dark background. The purity of white marble further emphasizes the clarity of the sculpture.

In Mary’s depiction, the physical features often associated with Michelangelo’s works are absent because the entire figure is surrounded by flowing drapery. It conceals any fleshiness one might expect in the portrayal. Mary’s hands are depicted in symbolic gestures symbolizing the deep connection between her and her deceased son. Through these gestures, the unity of their bodies is suggested, with Mary’s right hand supporting the body of Christ. Christ himself is depicted in a state of nudity, with only a narrow loincloth covering his loins. His slender form is delicately sculpted, with slender legs, bowed head, and right hand gracefully resting on his mother’s garment. The attention to detail in the anatomy of the figures reflects a deep understanding and skill in sculpting techniques.

In Christ’s portrayal, it is worth noting the position of His arm where it rests on His mother. The portrait presents an extremely realistic quality, skillfully blending the woman’s graceful fingers with the relaxed muscles of her son’s arm. Christ’s overall posture gives the impression of a figure who has just breathed his last, creating a poignant and emotional scene. Although there is noticeable distortion of proportions between the two figures, the artist approached the subject with great sensitivity and attention to detail. Mary’s slender frame is hidden beneath richly adorned clothing, adding a sense of modesty and reverence to the composition. The treatment by the artist of the signs of crucifixion and the wounds on Christ’s side is done with a delicate touch, emphasizing the seriousness and significance of these details in the artworks. The juxtaposition of tender maternal support and deep suffering of Christ evokes in the viewer a profound sense of empathy and contemplation. This image encourages viewers to reflect on the deep bond between mother and son, as well as on the sacrificial nature of Christ’s ultimate act of Love and Redemption. Overall, the work conveys a powerful message of faith, compassion, and the enduring legacy of Christ’s sacrifice.

Michelangelo meticulously attended to every intricate detail present in his masterpieces, from the sinews in Christ’s limbs to a careful gaze upon Mary. With precision, one can observe faint nail marks, graceful drapery of fabrics, and even a glimpse of Mary’s delicate foot emerging from beneath her garment. Furthermore, the meticulousness of the artist’s work is evident in the subtle imprints of Mary’s fingers adorning the inner palms, showcasing truly extraordinary levels of realism. Additionally, through skillful manipulation of depth in sculpting and expert polishing of marble, Michelangelo demonstrated a profound understanding of how light and shadow interact to breathe life into his sculptures.

The Pietà, Michelangelo’s sculpture, is created on a relatively small scale, with figures slightly smaller than life-size, yet effectively conveys a sense of monumentality in the scene. This effect is achieved through meticulous deep carving, assembly of elements, and careful polishing of marble. Michelangelo exhibited an exceptional level of skill in polishing Christ’s face, giving it an ethereal quality that seems almost weightless and timeless. Among Michelangelo’s works, the Pietà stands out as the only sculpture bearing his signature, discreetly placed on the fold of Mary’s garment at chest level (“MICHAELA [N] GELUS BONAROTUS FLORENTIN [US] FACIEBA [T]”). The intricacy and artistry of this masterpiece are a testament to Michelangelo’s unparalleled talent and knowledge in sculpture, making the Pietà a significant and iconic work in the history of art. This sculpture not only showcases the technical mastery of its creator but also conveys deep emotions and spirituality, capturing the essence of the subject with timeless elegance that continues to awe and inspire viewers worldwide.

A few days after the sculpture was publicly revealed, rumors began circulating that the work had been created by Cristoforo Solari. In response to these speculations, Michelangelo clandestinely inscribed his signature on the wing of Mary under cover of night. This act of secretly signing his works proved to be a unique event in Michelangelo’s artistic career, as he never repeated this action on any of his subsequent works.

In May 1972, the famous Pietà sculpture suffered significant damage at the hands of Laszlo Toth, an Australian geologist from Hungary. Toth wielded a hammer, repeatedly striking the masterpiece brutally, causing the left arm of Mary to break off up to the elbow, fracturing the nose, and causing serious damage to the delicate marble features. Shouting, “I am Jesus Christ!” during the destructive act, Toth shocked and horrified onlookers. Following meticulous reconstruction using a replica at the Church of Our Lady of Sorrows in Poznan, the Pietà was delicately restored and relocated to the Chapel of the Holy Cross to the right of the entrance of St. Peter’s Basilica, now secured with bulletproof glass to prevent future harm.

Leave a comment