The works of the Pre-Raphaelites, drawing inspiration from the artistic masterpieces of ancient masters, are currently showcased in an exhibition in Italy at the Museo Civico in Forlì, available for public until June 30, 2024. This exhibition serves as an inaugural presentation of works by renowned artists such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, as well as iconic figures such as Michelangelo, Botticelli, and Bellini.

Currently, over 300 artworks belonging to the 19th-century British artistic movement known as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood are being exhibited in Forlì, a city located near Bologna in Northern Italy. The formation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood took place clandestinely in London in 1848, initiated by seven men who were students of the Royal Academy and ranged in age from 19 to 23. These individuals were tired and frustrated with the stiff artistic conventions that characterized the Victorian British art scene.

The group consisting of William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, James Collinson, Frederick George Stephens, and Thomas Woolner was motivated by a common goal to rejuvenate English painting, perceived as in decline due to excessively formal and rigorous regulations enforced by the Royal Academy.

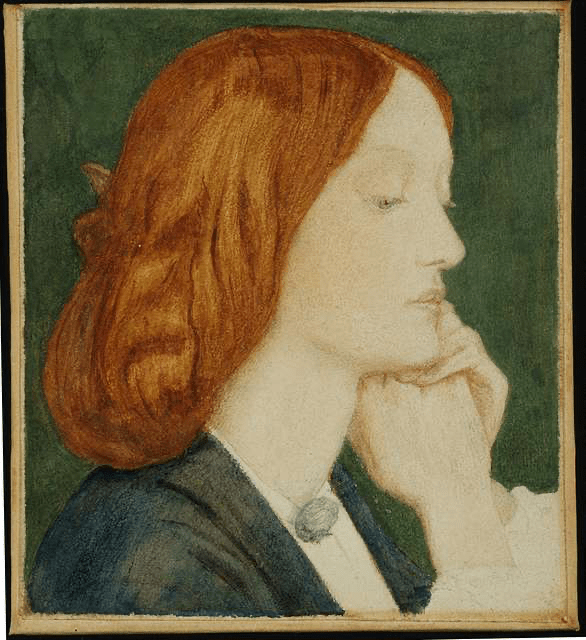

Enchanted by the art of the Pre-Raphaelite era, these artists cultivated a unique and distinctive style characterized by the portrayal of flame-haired women, vibrant colors, and meticulously detailed paintings. Although their works often delved into themes of social and patriotic significance, it was their portrayal of ideal feminine beauty that truly captured attention. This leads us to the intriguing figure of Elizabeth Siddal, one of their most famous muses. Who she really was, and what role did she play in inspiring their artistic creativity?

The remarkable tale of the famed beauty Lizzie Siddal is a narrative filled with wonder and sorrow. It encompasses not only her exceptional physical charm but also tumultuous romantic entanglements, burgeoning artistic talent, and an unforeseen and poignant conclusion, encapsulating the essence of a short yet vivid life led by this muse of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, whose fame endures to this day.

In the winter of 1850, artists Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt were engaged in a joint painting session in their studio when a visit from their acquaintance Walter Howell Deverell brought unexpected news. With palpable enthusiasm, Deverell revealed the discovery of a model of extraordinary beauty, whom he allegedly linked to royalty due to her towering stature. It was through this connection that the enigmatic Elizabeth Siddal was introduced to the world, swiftly transforming into a revered muse, whose legacy is still revered within the esteemed walls of the world’s most renowned museums.

The memory of the artist Walter Deverell, who died prematurely at the age of 27, faded from collective consciousness in contemporary times. However, during its brief existence, he played an active role in the circle of artists and writers revolving around the emerging Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. This secret association, consisting of seven youthful visionaries, was founded in 1848 by the trio of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Holman Hunt, and John Everett Millais, graduates of the esteemed Royal Academy in London. Apart from being a haven for talented individuals, the Pre-Raphaelite movement also embraced models, artists, and literary figures. It is worth noting that among the pioneering members of this fraternity was Elizabeth Siddal, whose trajectory began as a muse before blossoming into a skilled painter and poet.

At the time of her introduction to Deverell, Siddal worked in a milliner’s shop near Leicester Square, located in the bustling heart of London. Enduring arduous hours in inhospitable surroundings, her loved ones worried about her delicate health. It is likely that this concern prompted Siddal’s mother to make the surprising decision to allow her daughter to pursue a career as an artist’s model—a profession deemed scandalous and unworthy of respect in that era. Interestingly, Deverell refrained from directly pleading with Elizabeth’s mother for consent; instead, he requested the intervention of his own respected mother, a figure highly esteemed in their social circle, to negotiate the terms regarding compensation. Ultimately, Mrs. Siddal agreed to the proposed arrangement.

Initially, Lizzie Siddal began her career as a part-time model; nevertheless, after being introduced by Deverell as Viola in Twelfth Night, a nod to Shakespeare’s renowned work, she then sat for Holman Hunt on two separate occasions. The first instance occurred when she modeled for Rossetti in 1850, during the creation of one of his lesser-known works, Rossovestita. The enigmatic Dante Gabriel Rossetti not only meticulously sketched and painted Lizzie but also encouraged her to nurture her own artistic talents. What began as a mere artist-muse acquaintance gradually evolved into an intensely passionate and tumultuous relationship that lasted almost a decade. According to their benefactor, John Ruskin, Rossetti immortalized Siddal countless times throughout their shared lives.

In the modern era, Elizabeth Siddal’s slender figure, the emotional features of her face, and her shining copper locks are widely perceived as symbols of beauty; however, in the 1850s, slimness was not considered a charming trait. In fact, red hair was once described by some as “social suicide.” Through the efforts of this model and the recognition garnered by the artworks in which she was depicted, Lizzie played a crucial role in transforming the public perception of prevailing beauty standards at the time.

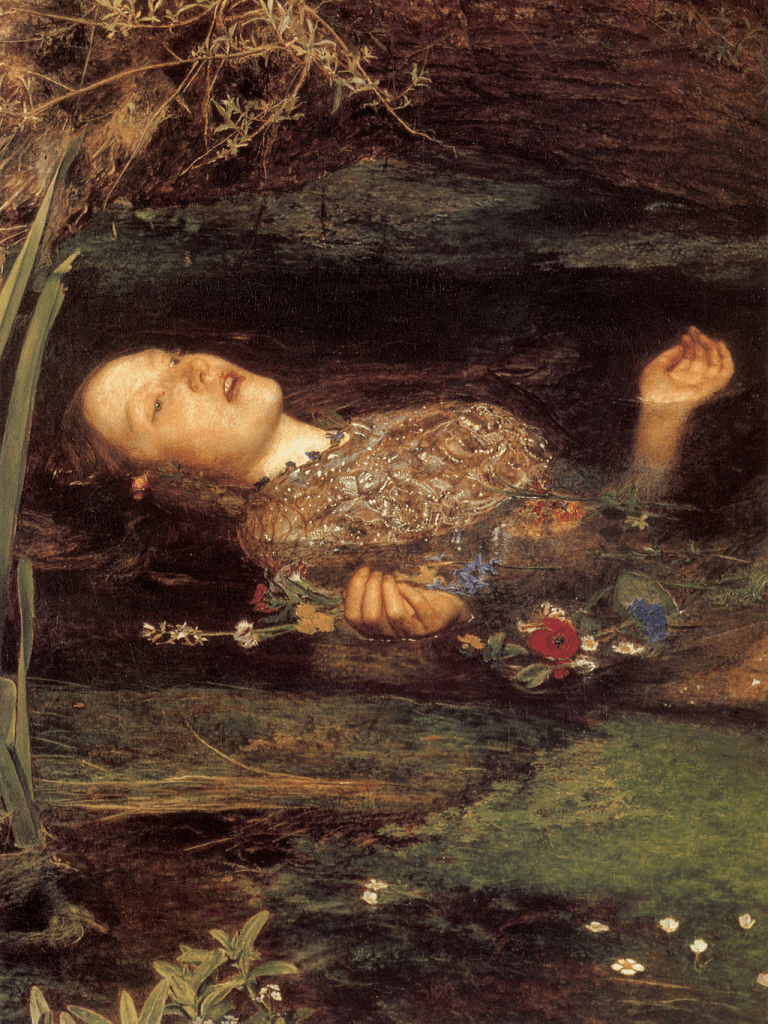

In a short span of time, Lizzie amassed sufficient earnings to bid farewell to her previous occupation in the dairy. After her famous portrayal as the muse of Millais’s iconic Ophelia, her visage became unmistakable. Siddal’s reputation soared to such heights that many artists sought to immortalize her likeness on their own canvases. Nevertheless, Rossetti posed a significant obstacle to the burgeoning modeling career, as his possessive nature led him to insist that she exclusively model for him. The romantic saga of Siddal and Rossetti bore the semblance of a melodramatic plotline, neither of them being simple life partners. Siddal struggled with laudanum addiction, while Rossetti proved to be an unfaithful companion. After several tumultuous years together, they eventually exchanged vows in May 1860 at St. Clement’s Church in the seaside town of Hastings, without the presence of family or friends, only a handful of witnesses they met in Hastings.

After years of hiding her artistic talent in the shadows and receiving guidance from Rossetti, Siddal embarked on her artistic journey in 1854, marking the beginning of a significant chapter in her life. Despite harsh criticism from art critics regarding her paintings, Siddal, a determined young woman, was just beginning to explore the intricate world of art, diligently creating her own creative space. Meanwhile, male artists from her social circle honed their skills for many years under the tutelage of esteemed experts. Siddal’s remarkable and rapid progress caught the attention of Ruskin, who early on recognized her potential and bestowed upon her the rare title of “genius.” In a generous gesture, Ruskin offered her a yearly stipend of £150 to support Siddal in her artistic endeavors and development.

Interestingly, during this period, Siddal earned a modest £24 per year, devoting herself full-time to a prestigious hat shop. In a pivotal moment for female artists, Siddal became the only woman to exhibit her works at the prestigious Pre-Raphaelite exhibition in London in 1857. Subsequently, grappling with worsening health conditions and strained relationships within her circle, Siddal made the difficult decision to part ways with the financial support of her patron. Under the influence of Rossetti and Ruskin, Siddal found herself restricted in various aspects of her life, fostering a desire for liberation.

Using her savings, Siddal arranged a retreat to Matlock Spa in Derbyshire accompanied by one of her sisters. Instead of returning to the bustling streets of London, she chose to go to Sheffield, her father’s birthplace, seeking solace in the presence of extended family. After these events, Siddal decided to reside in a hostel and enroll in the esteemed Sheffield School of Art, embracing ambitions of becoming an independent and successful artist.

Rossetti maintained regular communication with Lizzie, making periodic visits to see her. However, his interactions with friends from London soon revealed his involvement in numerous romantic relationships with other women, ultimately leading to the end of their relationship in mid-1858. A veil of secrecy shrouds many events that unfolded in Elizabeth Siddal’s life in the ensuing years. In the spring of 1860, Lizzie’s health began to deteriorate, and news of her poor condition reached her former beloved, prompting him to return to provide support during her difficult time. Subsequently, after Elizabeth’s recovery, their bond was strengthened by their marriage ceremony at St. Clement’s Church.

Before long, Lizzie realized she was expecting a child. The thought of becoming a mother brought her immense joy. Unfortunately, her happiness was short-lived as she struggled with the unfortunate consequences of her laudanum addiction. It was around May 1861 when Siddal faced the agonizing pain of delivering a stillborn daughter. The weight of this loss plunged Elizabeth into deep despair, from which she never truly emerged. Thus, the already tense structure of their marital relationship faced additional strain due to the challenges they encountered, and once again, suspicions of Rossetti’s infidelity plagued her thoughts.

Trapped in times when addiction was shrouded in taboo, and understanding of postpartum depression was elusive, Siddal was left to grapple with an unrelenting cycle of illness, addiction, and sorrow following the tragic death of her child. Despite relentless efforts to channel her inner turmoil into creative endeavors, a battle she was denied by many women of her time, Lizzie found herself ensnared in the grip of addiction, a battle she ultimately tragically succumbed to.

On the evening of February 10, 1862, as Rossetti went to an evening class at the Working Men’s College, he came across Lizzie peacefully resting in bed, having just taken her daily dose of laudanum. Upon his return, he discovered that the bottle of medicine had been emptied, and Lizzie was in such a deep slumber that all his attempts to awaken her were in vain. Instead of leaving without a word, Siddal decided to leave a poignant farewell letter for her husband, which he, upon the advice of a trusted friend, chose to consign to the flames. This act, in hindsight, spared the woman from posthumous stigmatization as a suicide, a stigma that would have precluded a Christian burial. The weight of the tragedy never truly left Dante Gabriel Rossetti, as he carried immense guilt over the loss of his wife to suicide, a remorse that haunted him for the rest of his days. The artist grappled with persistent insomnia and recurring bouts of depression.

Nevertheless, Lizzie’s narrative did not end with her untimely death. Instead, several years after her passing, an extraordinary story began to unfold, casting her as a revered Gothic icon. The genesis of this story traces back to Rossetti’s poignant gesture after his beloved’s death when he placed in her coffin the only existing copy of verses he had written. These verses, surrounded by her famed chestnut locks, remained in his thoughts for many years, compelling him to eventually seek their retrieval for publication seven years later.

In great secrecy one autumn night in 1869, Siddal’s coffin was exhumed from its resting place in London’s Highgate Cemetery. Rossetti, whom some acquaintances considered mad, did not appear during the entire affair. The exhumation was overseen by the artist’s friend, Charles Augustus Howell. With no lights in the cemetery, a large fire was lit. Howell later told Rossetti that upon opening the coffin, he beheld Elizabeth’s body immaculate and beautifully preserved. She was not a skeleton, he falsely claimed; she remained as beautiful as in life, and her hair had grown to fill the coffin with a gleaming coppery light that shone in the firelight. In Howell’s gloriously fabricated fiction emerged the myth of the enduring beauty of the original supermodel, even in death, a myth that ensured that to this day, many people around the world believe Siddal remained undead, which, of course, from a biological standpoint, is utterly impossible. While cellular growth does not occur after death, nonetheless, the propagated tale enriched Lizzie’s legend and continues to pique the interest of Pre-Raphaelite enthusiasts and Lizzie Siddal admirers.

Elizabeth Siddal passed away at the age of 32, but her extraordinary legacy is evident to this day. The recovered poetry of her husband was published with great acclaim—although the story of its origins was carefully guarded.

Leave a comment