Over the past four years, Turkey’s digital art scene has undergone a significant transformation, gaining widespread visibility amid the pandemic. This newfound interest has culminated in a renaissance of sorts, bringing both excitement and concern, as the surge in popularity risks overshadowing the rich history of digital art in Turkey.

It is important to recognize that this bloom in activity has been largely facilitated by support from governmental bodies, the Istanbul municipality, and private enterprises, despite their often contentious relationships towards each other. While the increase of attention and investment in digital art may seem like a positive development, there is a chance that it could devolve into a superficial spectacle, devoid of critical discourse.

In recent times, numerous exhibitions have emerged mostly across Istanbul, each heralded as a pioneering event. These gatherings attract large crowds eager to capture selfies amidst the showcased digital artworks. The promotional efforts surrounding these exhibitions imply a novelty to digital art in Turkey, overlooking longstanding explorations of digital mediums and significant contributions to the global digital art landscape made by Turkish artists. Therefore, a brief historical recap of Turkey’s digital art scene is warranted to provide context and foster informed discussion within the current enthusiasm.

Digital art in Turkey experienced a delayed but significant emergence, despite its inception in the West several decades prior. While the inaugural exhibition, Computer Art: The Works of the Ars Intermedia Group took place in 1975 at Istanbul Technical University’s Faculty of Architecture, it wasn’t until the late 2000s that digital art gained substantial visibility across the art scene. This lag of forty years was mitigated by the concerted efforts of individual artists, collectives, and academics.

Noteworthy among these pioneers are Teoman Madra, Hamdi Telli, and Nil Yalter, who spearheaded digital art as the first national practitioners, alongside architect Ilhan Mimaroğlu and composer Bülent Arel. Their pioneering contributions laid the foundation for subsequent advancements in the field. Further enriching the landscape were figures like Genco Gülan, Orhan Cem Çetin, Server Demirtaş, and Murat Germen, who made significant strides in digital art during its nascent stages in Turkey.

Through their dedicated endeavors, these artists and intellectuals played pivotal roles in bridging the temporal gap between the inception of digital art in the West and its flourishing in Turkey, thereby catalyzing its growth and integration within the country’s artistic milieu.

Beral Madra is widely acknowledged as a pioneering figure, notably as the first curator to embrace digital artworks in the early 1990s. However, preceding her efforts, several seminal initiatives laid the groundwork for the development of Turkish Digital Art. Projects such as Nomad, Web Bienal, Techne, and the Amber Festival, in which I later had the privilege to contribute my own works and research, played pivotal roles in this trajectory.

Of these initiatives, the Amber Network Festival stands out as the sole project to persist into the present day, a testament to its enduring impact and relevance. Led by its co- creator, Ekmel Ertan, the festival continues to serve as a vital platform for the promotion and advancement of digital arts within Turkey and beyond.

Since the early 2000s, significant advancements in the field of digital art have been attributed to the establishment of dedicated visual communication design departments within prominent universities. Istanbul Bilgi University’s Visual Communication Design (VCD) department, in particular, has emerged as a prominent influencer through its pioneering initiatives, notably its annual Track exhibitions. These platforms have served as catalysts for innovation by fostering interdisciplinary dialogue within the field.

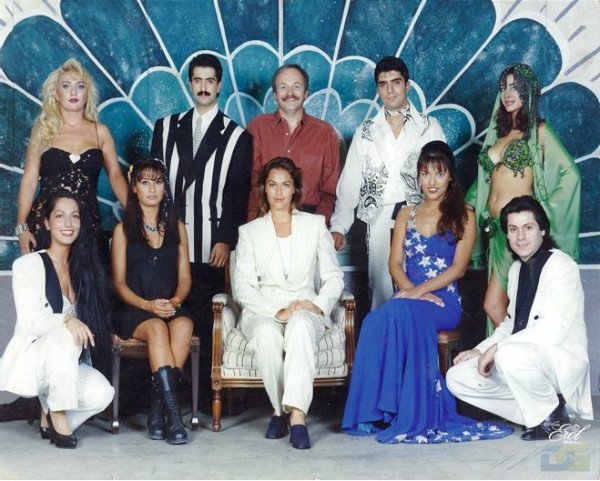

It is important to note that the 1990s were marked by widespread televised propaganda, with media literacy remaining largely inaccessible to the general population. Setting aside the consideration of digital media as an art form, Turkish cinema had already fostered mythologies that reshaped perceptions of artistic identity. The emergence of meticulously groomed pop stars and television celebrities led to their classification as ‘’artists’’ blurring the traditional boundaries of the term. This phenomenon predated the extensive influence of social media, highlighting a significant shift towards ambiguity in defining artistic roles long before the digital era’s mass-scale impact.

During the 2000s, media art or digital art faced challenges in gaining broad recognition in the public intellect. Unfortunately, this led to the art scene missing out on a rich discourse present in Western countries, where video art, expanded cinema, light and sound art, as well as other forms of media or digital art, were deeply integrated into critical dialogue.

Despite the oversight of media art (notably excluding Ura Gallery’s Nam June Paik exhibition), the latter half of the decade witnessed a significant leap for New Media Art. During this period, this ‘’new’’ field began to gain prominence, visibility, and critical acclaim within the art scene. Artists such as Burak Arıkan, Ali Mirhabi, Osman Koç, Ozan Türkkan, Pınar Yoldaş, Memo Akten and curators such as Başak Şenova, Ceren & Irmak Arkman were increasingly becoming familiar names in the art world.

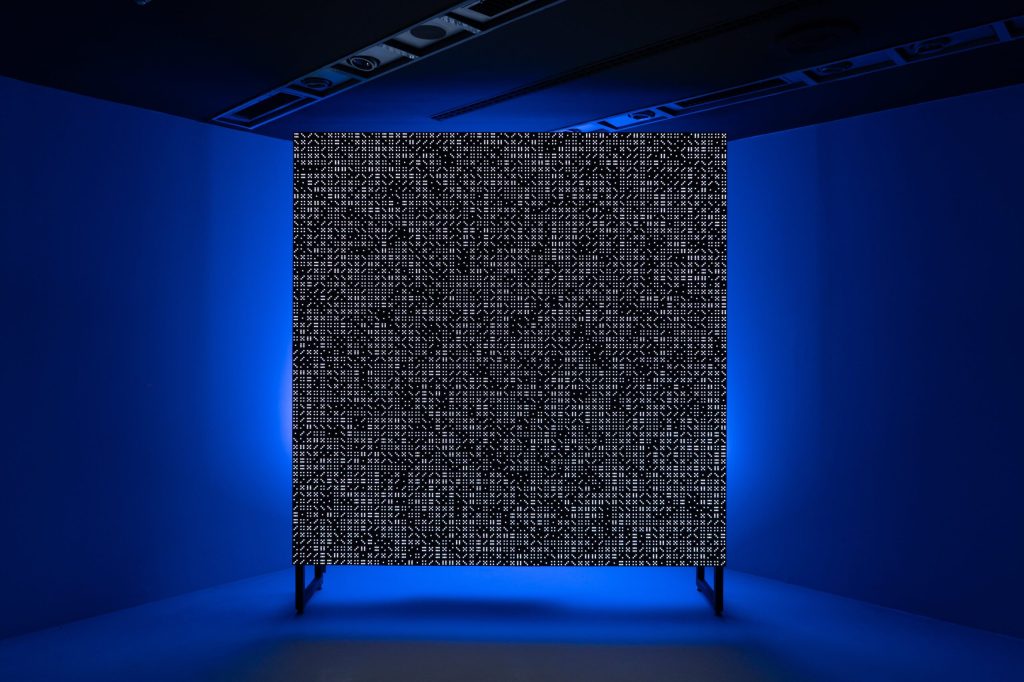

Around the same period, notable artists have ventured into establishing their creative brands, exploring the intersection of art, design and technology. Candaş Şişman collaborated with Deniz Kader to co-create Nohlab, while Refik Anadol partnered with Maurizio Braggiotti and Efe Mert Kaya to found Antilop. Additionally, Erdem Dilbaz pioneered the collective initiative Nerdworking, introducing the concept of ‘’producing for digital arts’’. While the latter three groups primarily explored a combination of video projection, sound art, and performance, the integration of Artificial Intelligence had yet to become prevalent in the field. The works produced were nothing close to a mere visual spectacle and despite their abilities to put masses in awe, they strongly suggested critical elements to wonder upon.

It’s crucial to acknowledge that fifteen to twenty years ago, the interpretation of these works differed significantly, with the concepts of ‘’digital canvases’’ and ‘’image-spaces’’ carrying significant weight. The convergence of physical and digital realms prompted profound questioning and exploration, challenging conventional understandings of art and perception. Indeed, these mediums represented both extensions and revivals of older art forms and experiential designs, reminiscent of early 19th-century panoramas and dioramas. They amalgamated various elements of experience design, drawing upon concepts from architecture, cinema, painting, and light art. It represented a synthesis of diverse creative expressions, offering a renewed exploration of the intersection between physical and non-physical realms.

In the absence of a widespread craze for virtual spaces, a landscape of unexplored territories unfolded, offering fertile ground for discovery. At the forefront of this exhilarating exploration were numerous Turkish digital artists, leading innovation and pushing boundaries within the evolving digital landscape. By the start of the 2010s, the digital art scene had reached a point of full bloom and autonomy, flourishing independently. However, galleries, museums, and art institutions within the country began showing a hesitant and gradual interest in embracing this burgeoning movement. As major digital art festivals thrived in European countries, Turkish digital artists garnered significant recognition, earning numerous major art prizes. Despite the excitement surrounding these achievements, there was a prevailing sense of despair as much of this success went unnoticed within their homeland.

Thanks to the dedicated efforts of independent practitioners, the years 2010 and 2011 marked significant milestones where digital art finally gained visibility in Turkey. While the Pera Museum hosted the ‘’Japanese Media Arts Festival’’ in 2010 and Borusan presented ‘’Matter-Light’’ in 2010 and 2011, these events did not fully represent the Turkish Media Art scene. However, a notable exhibition that deserves recognition is Lalin Akalan’s ‘’Affective State’’ held in the historic Tophane-İ Amire quarters during the Istanbul Biennial in 2011. As the first exhibition of its kind, it comprehensively explored immersive art and showcased emerging digital artists of the time, including myself.

With perseverance, the field of media art had finally emerged into prominence. While there was a noticeable trend towards video mapping, artists continued to demonstrate a diverse range of creativity and expression, showcasing the breadth of possibilities within the discipline. The reality is that gatekeepers often lacked the necessary knowledge to accurately label or distinguish between the diverse forms of media art. For instance, in 2011, one of my 16mm films was showcased on Turkey’s first online art platform. Despite my insistence, the work was mistakenly categorized as video art. This period resonates with Brancusi’s Bird in Flight case, where US officials struggled to categorize the piece as art, leading to a court case questioning its artistic merit. Similarly, today’s inquiry shifts from ‘’what is art?’’ to ‘’what is new?’’, reflecting the evolving nature of creative expression and the challenge of defining innovation in contemporary art.

The prevailing uncertainty surrounding digital art catalyzed the emergence of a vibrant and authentic chapter around 2014. During this time, artists, feeling misunderstood within conventional art circles, embarked on creating independent art initiatives. These endeavors aimed to cultivate fresh dialogues and explorations, marking an exciting and transformative chapter in the evolution of digital art in Turkey. Prizmaspace was my co-contribution to this field; a space dedicated to expanded cinema. Seyhan Musaoğlu’s Space Debris specialized in sound and performance, while the newly established collective art initiative Decol predominantly focused on immersive experiences. Together, these diverse initiatives along with others enriched the artistic discourse and offered unique platforms for experimentation and expression within the digital art scene.

During this period, prior to the pervasive influence of social media, digital artists experienced a golden age of creativity and innovation. Against the backdrop of recent mass protests, young artists felt a surge of hope and inspiration. Thriving in underground circles, akin to a lotus flower emerging from mud, digital art blossomed. Despite facing limited resources, it flourished in its most refined state, embodying the essence of artistic creativity.

Around the same time, curators Derya Yücel and Ebru Yetişkin made impactful digital art exhibitions and significant contributions within the field. Meanwhile, I had the opportunity to participate in Istanbul’s inaugural Light Festival. Artists such as Can Büyükberber, Ayşe Gül Süter, Selçuk Artut, Büşra Tunç, Erdal İnci, and Nihat Karakaşlı were emerging as notable figures in the field. It is worth noting the significant contributions of academician Bager Akbay, who has been actively involved in the field, earning prominence within the scene. Additionally during the same period, the media art section Plugin was established at the renowned art fair Contemporary Istanbul, while Şekerbank inaugurated Açıkekran, a space dedicated to media art.

Towards the end of the 2010s, preceding the pandemic, the field of digital art reached a significant milestone, establishing itself firmly within the art world. Exhibitions showcasing digital art were on the rise in popularity, almost overshadowing other forms and asserting their dominance in the art scene. Zorlu Performance Center was launched, with curator Lalin Akalan organizing several impactful Media Art exhibitions under her brand Digilogue. Concurrently, Akalan curated the annual program for the then newly established Sonar Istanbul. Bilsart, despite ethical concerns surrounding its owner’s treatment of female artists, established itself as a leading venue for showcasing video art. Meanwhile, Turkey’s inaugural Digital Art Festival was curated by Seyhan Musaoğlu.

Around this period, beginning with X Media Art Museum curated by Esra Özkan, experience design with strong entertainment elements began to be classified as New Media Art. This trend gave rise to the emergence of ‘’museums for the arts without artists’’, featuring productions centered around figures like Leonardo da Vinci and Nikola Tesla.

Around this juncture, these creations marked a pivotal shift, as New Media Art became largely synonymous with this particular strand, embodying a distinct mindset, production structure, and perspective. This evolution would eventually pave the way for the emergence of NFT artists. Consequently, traditional Media Art became overshadowed, as New Media Art embraced a singular yet paradoxical vision.

At the end of the decade, amid the pandemic, online selling platforms emerged but proved ineffective. However, digital art, being the most accessible to produce and share, experienced an even greater surge in popularity. The widespread digitization prompted both new and established artists to pivot towards digital mediums, leading to the emergence of new talent in the post-COVID art scene. Artists such as Ecem Dilan Köse, Yağmur Uyanık, Ahmet Rüstem Ekici, Hakan Sorar, and the artist duo Ha:ar gained increased recognition. The duo also initiated PikselArt, a platform dedicated to the production, exhibition, and support of new media art.

During the same period, Istanbul The Lights festival, co-produced with support from the Istanbul Municipality – in which I participated – was launched in parallel to the Contemporary Istanbul art fair, which itself was cancelled that year due to restrictions concerning the pandemic. It is worth noting that despite the genuine enthusiasm of its curators, the project suffered from a lack of organization and realistic budgeting. Though I had previously participated in ‘’Turkey’s first Light Festival’’, this event was again marketed as such. In subsequent years, a third festival proposal from the municipality, although canceled, offered me a commission. I declined due to their continued insistence on branding it as yet another ‘’Turkey’s First Light Festival’’.

During the pandemic, Akbank Sanat, a prominent art institution, launched the Digital Art Now series, where I participated. Under the guidance of curator Zeynep Arınç, the series promoted national digital artists through short videos on YouTube and later as a physical exhibition. While the ‘’new media art’’ aesthetic was prominent in their selection, it is crucial for me to acknowledge Akbank Sanat’s support for diversity in media art, as it has later supported me for a major expanded cinema exhibition I had the chance to showcase in its premises. During the same period, Senkron was initiated as a collaborative effort to organize synchronized video art exhibitions across diverse art institutions and organizations. I also had the chance to participate in this initiative with a solo screening.

Navigating the complex aftermath of the pandemic, art also found itself employed to bolster the reputation of various entities, including institutional, governmental, and commercial bodies. In some instances, this emphasis on promotional value diminished its critical potential. However, with forward-thinking vision and openness, rare opportunities arose for those seeking to diversify the discourse and enrich the field with a variety of perspectives and dialogues.

Despite the successful establishment of a digital art scene through collaborative efforts of artists, curators, academics, initiatives, and at last institutions, Turkey faced significant challenges such as major uprisings, rapid political shifts, a military coup attempt, and subsequent natural disasters. Frustrated by the lack of support prior to the pandemic, many independent practitioners chose to relocate abroad, maintaining a diminished presence in their homeland while garnering increased international recognition.

It is evident that the digital art field, initially shaped and guided by academicians and their students until the late 2000s, has since experienced a shift in dynamics. The prevailing atmosphere has been somewhat partially inherited by a further fatigued academic community, occasionally exhibiting weariness and disdain towards newcomers and even their peers. Academic vanity persists to this day, contributing to the ongoing challenge of fostering a genuine dialogue and cohesive community within the field. Despite numerous attempts, the creation of such a community has proven to be challenging.

A significant factor contributing to the regression of the field, alongside its expansion in certain aspects, is the approach of major companies towards digital art. Collaboration with advertising agencies often revolves around metrics like an artist’s Instagram followers and anticipated likes on Instagram posts. This approach fosters the creation of ‘’instagrammable’’ art, emphasizing superficial qualities like beauty and novelty, promising an exclusive experience. However, art cannot be reduced to the latest trend or a form of personal growth therapy. It should confront and engage with the complexities of existence, rather than serving as a mere escape. Today, more than ever, there is a pervasive sense of concealment, where what is visible obscures deeper truths. Ticketed “art” events often mask the labor involved in art, or worse, undermine it. Perhaps a reinterpretation of Magritte’s famous quote—‘’everything we see hides another thing’’— aptly captures the current state of affairs.

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly transformed our lives, reshaping not only how we create art but also how we sustain ourselves through it. It ushered in novel forms of communication and prompted fresh perspectives on artistic expression. Like indigenous inhabitants caught off guard by an unexpected snow avalanche, many found themselves displaced from the art industry post-pandemic, while newcomers swiftly established themselves. This shift prompted artists to confront a critical dilemma: Will you compromise artistic integrity for commercial gain? Despite ongoing uncertainties surrounding NFTs and the evolving intersection of experience design and art, the digital art landscape has shifted away from questioning technology and instead embraced its uncritical acceptance. In this context, how can digital artists navigate the pursuit of financial success while maintaining genuine authenticity in their work?

In Turkey, artists typically navigate three distinct avenues for sustaining their artistic careers, each marked by its unique gatekeeping mechanisms. ‘’Serious Artists’’ find their work showcased in prestigious biennales, museums, and galleries. However, over the past two decades, this sphere has remained remarkably stagnant, with mostly same artists and curators dominating the scene. Space for digital artists remains limited. Another path lies in becoming an ‘’Art Fair Artist’’, where works must possess Instagram- friendly appeal, offering easily digestible entertainment for a broad audience and tailored for domestic consumption with the intention to adorn living room walls as decorative pieces. The third avenue is that of ‘’The Commission Artist’’, where established recognition, preferably international, is essential for securing commissions from institutions, brands, or companies. However, this route risks reducing art to mere design, devoid of critical engagement. Unlike in Western cultures, these paths rarely intersect in Turkey, highlighting the absence of a cohesive framework that integrates these diverse approaches. Unfortunately, a fourth option has yet to emerge to address this gap.

Government funding or municipal support could have served as a crucial fourth avenue for artists, as it forms the foundation of artistic growth in many countries. Despite significant expansion of opportunities for digital art over the past five years, it is evident that this support primarily served as a vehicle for political agendas.

Upon the conclusion of the initial COVID-19 confinement measures, digital art in Turkey assumed a pivotal role, not only as a mode of creative expression but also as a tool for mass promotion. Positioned as a conduit for showcasing cutting-edge innovation, it was harnessed by political entities to project an image of progress and access to the latest advancements.

The long awaited iconic culture center AKM’s re-opening after its renovation was inaugurated by the state and presented with a digital art festival as its highlight. Amidst the prevalent narrative of embracing cutting-edge technology within the diplomatic sphere, artists found themselves increasingly entangled in the political discourse. This trend reflected a broader phenomenon wherein creative practitioners took discernible positions within the socio-political landscape, navigating the intricate interplay between artistic innovation and ideological alignments.

The decisions made by both the government and its political opponents, particularly the municipality of Istanbul, have been criticized for lacking strategic vision, leading to a notable regression in the digital art field. Despite appearing progressive, these initiatives have primarily focused on captivating audiences rather than fostering substantive development.

The municipality of Istanbul’s efforts to promote the field, such as the establishment of new digital art museums curated by organizations like Ars Electronica, have drawn criticism for providing limited opportunities for Turkish digital artists and curators. Similarly, the introduction of a digital experience museum, while initially promising, has fallen short in its context. Despite its name and description suggesting an emphasis on artistic and design-specific experiences, it predominantly features works produced by agencies, rather than highlighting individual artists or designers.

In contrast, the Open Call for young media artists stands out as a more promising avenue of support. This initiative offers an inclusive platform for emerging talents to showcase their work, potentially contributing to the advancement and diversification of the digital art landscape in Turkey.

Despite the considerable dedication and talent exhibited by numerous artists and curators within the digital art sphere, many have struggled to secure the necessary support for their endeavors. While opportunities for assistance have seemingly become more available, in practice, this support often fails to materialize, leaving individuals in the field facing significant challenges. Consequently, a substantial portion of the artists and curators mentioned earlier in this discourse have been compelled to either transition away from their artistic pursuits or face significant constraints within their practice.

Moreover, the absence of robust critical discourse within the general public further exacerbates the challenges faced by the digital art community. As a result, art continues to be perceived as enigmatic and inaccessible to many, perpetuating a sense of mystique surrounding the field. Additionally, the politicization of art has led to the polarization of artists and institutions, with individuals aligning themselves with particular political factions and harboring prejudice against institutions supported by opposing parties. This divisive atmosphere underscores the broader societal impact of political influence on cultural expression, highlighting the need for greater understanding and support of the arts in Turkey.

The perception of an artist within the Turkish public consciousness starkly contrasts with that in other global art centers like London. While individuals like UK based artist Jesse Darling, celebrated for their unconventional identities, receive acclaim and recognition internationally, the prevailing image of an artist in Turkey often evokes that of a traditionalist, perhaps an older male figure known for meticulous realism, such as painting seascapes adorned with fish—a stereotype that persists despite the evolving landscape of contemporary art.

Furthermore, critical thinking within Turkey’s cultural sphere has been hindered by the prevalence of platforms like EkşiSözlük, which translates to ‘’Bitter Dictionary’’ in English. This online forum, dating back to the early 2000s, has emerged as a significant platform for information exchange. However, its utility is tempered by the presence of biased perspectives, often driven by frustration and negativity rather than objective analysis. This mode of critical engagement has inadvertently shaped aspects of our cultural discourse, influencing perceptions and attitudes in ways that may not always promote balanced or constructive dialogues.

Throughout this complex and evolving process, it is important to recognize the contributions of artist Kerem Ozan Bayraktar, who is engaged in rigorous critical exploration within the field. Curatorial efforts led by Ceren and Irmak Arkman at Kalyon Kültür have provided valuable platforms for introducing fresh discourses into the digital art sphere. Additionally, the artist duo Ha:ar established the digital art fair, Noise Fair, with the support of the Istanbul Municipality. While the fair showcased a diverse array of national and international media art, some may argue that it did not fully represent the breadth and depth of Turkey’s national artistic scene. Nevertheless, it is essential to acknowledge the positive intention behind such initiatives, as they play a vital role in promoting digital art within the local context and fostering dialogue within the artistic community.

Despite these commendable endeavors, the emergence of ‘’New Media Art’’ has ushered in a popularization of the field, often simply emphasizing the incorporation of the latest technological innovations. It is increasingly evident that influencers play a significant role in shaping the guest list at exhibition openings. Moreover, projects seeking support from major stakeholders must appeal to a broad audience and captivate the masses. As a result, mesmerization has become a central element in the creative pursuits of digital artists.

A striking example of this trend is demonstrated by the Turkish art duo Ouchhh, who garnered significant attention for sending the first NFT artwork to the moon. Concurrently, the Turkish government’s sponsorship of a non-astronaut to embark on a space mission with SpaceX occurred. These endeavors, marked by their ambitious scale and assertive execution, underscore a prevailing paradigm where commercial priorities frequently take precedence over cultural and scientific pursuits.

In societies such as ours, there is a prevalent inclination towards seeking validation from abroad, particularly in Europe or the United States, as a measure of an individual’s achievement. It was not until the mid-2010s that many dedicated digital artists amassed adequate experience and recognition internationally, allowing them to finally receive acclaim from their own communities. However, it’s noteworthy that in countries such as ours, social media presence and follower count also influence an artist’s selection for support.

In today’s artistic landscape, artists are increasingly required to embody diverse roles, encompassing academia, influence, and entrepreneurship. The necessity arises from the reality that supporters must be actively courted, as acknowledgment and patronage are often not forthcoming without proactive efforts. Consequently, artists find value in cultivating either fame or academic credibility, both of which hold sway in attracting supporters. Given the prevailing lack of vision, expertise, and critical understanding, collaborating with reputable academicians or influential figures within the field emerges as a prudent strategy.

In our society, where individuals are frequently left undereducated, there’s a prevalent belief in the superiority of academics, though it’s intertwined with complex. This has resulted in the mystic idealization of ‘’the teacher’’ where the authority of educators is rarely questioned. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that the proliferation of universities has not necessarily equated to an improvement in educational quality. Turkey continues to rank unfavorably in national education metrics, reflecting systemic shortcomings in the educational system.

A similar trend is evident in the frequent inauguration of new museums and art spaces. However, the increasing prevalence of the term ‘’digital art’’ paradoxically leads to its diminished significance over time. Despite the growing number of venues, there is a notable decline in the diversity of digital art representations, raising concerns about the loss of variety within the artistic field.

In regards to my own artistic endeavors, I have noted an intriguing observation regarding my video artworks, which are now perceived as ‘’not new enough’’ yet still encounter difficulties in being displayed properly. During my recent participation in an exhibition curated with the support of a prominent holding company, I was disappointed to find that my four-channel video installation was not properly showcased. Regrettably, three out of the four screens were not working and as indicated by images shared on social media, left unrepaired. The curator expressed discontent with the insufficient technical support available. Nevertheless, it was evident that in the event of a malfunction with their telephone screen, they would promptly arrange for repairs to be carried out. This observation highlights the notable difficulties that media artists still encounter when seeking to exhibit their work effectively.

As we conclude with a sense of disappointment, it is apparent that certain names of artists, curators, or institutions may have been inadvertently overlooked in my list. Contemporary discourse surrounding the history of art has increasingly been influenced by adept communicators and skilled tradesmen, a trend that has persisted over time.

Presently, the art world is experiencing a notable increase in digital art museums, exhibitions, and events, indicating a significant shift in cultural engagement. However, in the midst of this abundance, questions emerge about the critical aspects of these entities.

The advent of digital art has undeniably opened new avenues for artistic expression, inviting viewers to engage with innovative forms and mediums. Yet, the seemingly safe and mesmerizing nature of digital art may belie deeper complexities. While digital platforms offer accessibility and interactivity, they also raise concerns regarding the durability and authenticity of artistic expression in an increasingly digitized world.

Moreover, the novelty of digital art must be scrutinized within the broader context of artistic evolution. While technological advancements have undoubtedly expanded the creative toolbox, novelty alone does not necessarily equate to artistic significance. Rather, the true impact of digital art lies in its ability to challenge established norms, provoke critical discourse, and resonate with audiences on a profound level.

In this dynamic landscape, the role of political and popular demands cannot be overlooked. As societal values and cultural preferences shape artistic production and consumption, digital art finds itself situated within a nexus of intersecting influences. Consequently, the contemporary digital art scene becomes a reflection of broader socio- political currents, where issues of identity, representation, and power dynamics intersect with artistic practice.

In navigating these complexities, it becomes imperative for scholars, curators, and art practitioners to adopt a nuanced approach to the study and appreciation of digital art in Turkey. By critically examining its socio-cultural implications, interrogating its aesthetic conventions, and foregrounding its transformative potential, we can hopefully come closer to uncovering the true depth and significance of digital art within the Turkish contemporary art scene.

Leave a comment