Pliny the Elder, in his famous work Natural History, vividly described the renowned sculpture known as Laocoön. Pliny’s detailed work of literature had been the sole source of knowledge about this masterpiece for centuries, as its whereabouts remained a mystery. The ancient sculpture was unexpectedly unearthed during excavation works in a vineyard on the Esquiline Hill, amidst the ruins of the Baths of Titus on January 14, 1506. At the time of its discovery, the sculpture was fragmented, with some parts missing, but the recovered elements allowed witnesses such as Michelangelo and the Florentine architect Giuliano da Sangallo to confirm them as the renowned Laocoön Group, previously known only from ancient texts.

The journey of this masterpiece continued when Pope Julius II acquired the sculpture in the summer of 1506, making it a valuable addition to the Papal Collection of antiquities. The missing elements were then meticulously restored, Laocoön’s arm was reconstructed with a powerful upward gesture, and the younger son’s arm was depicted in an equally emotional pose. The figure of the elder son, once detached from the composition, was relocated parallel to others.

These renovations, now considered inaccurate, survived until the post-World War II era, significantly influencing the interpretation of the sculpture. From the 16th to the mid-20th century observers encountered falsely reconstructed Laocoön Group, where both Laocoön and his younger son had their arms dramatically raised.

During Napoleonic Wars, numerous works of art, including the Laocoön Group, were transported to Paris. Interestingly, modern weapon additions were left in Rome. After Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo and the subsequent repatriation of looted artworks in 1816, the Laocoön Group was returned to the Eternal City. Here, Antonio Canova, an eminent sculptor of the time, reintroduced the arms previously removed from the sculpture.

A significant breakthrough occurred in 1906 when the German archaeologist Ludwig Pollak stumbled upon the original arm of Laocoön, that was considered as lost. This discovery, located near the initial discovery site on the Esquiline, depicted an arm with a distinct posture compared to the Renaissance reconstruction. However, it took another fifty years to reattach the original arm to the rest of the sculpture. The divergent positions of both the original and reconstructed arms serve as a poignant reminder of the challenges associated with the restoration of ancient sculptures, highlighting the errors that may arise in such endeavors.

Throughout the modern era, the dominant method employed for conserving ancient artifacts was known as “restauro integrativo,” which involved reconstruction by adding missing elements, a practice exemplified by the restoration of the Laocoön Group. During the Renaissance period, it was common to join preserved fragments of ancient artworks that had been fragmented. The rediscovery of ancient sculptures, fragmented by the passage of time and neglect, was met with a desire to restore their original form, a sentiment prevailing until the 19th century when discussions regarding the appropriateness of such interventions began.

In the Renaissance era, conservators perceived Laocoön’s figure as a significant central element harmonizing movements and representing the pinnacle of composition, evident in the dynamic portrayal of the figures. Therefore, the reconstruction carried out in the 16th century reflects how conservation efforts mirrored the artistic preferences of that time.

The positioning of the arms by the contemporary sculptor reflects the mindset influenced by Renaissance ideologies. Ancient observers interpreted Laocoön’s posture as an acceptance of fate, emphasized by a sense of excessive restraint. The concept of bent arms conveyed a sense of emotional restraint in artworks. Conversely, outstretched arms symbolized aspirations for freedom and determination, characteristic traits of the Renaissance era, which championed individualism and unwavering resolve. While ancient craftsmen emphasized downfall and the inevitable nature of fate, Renaissance philosophy celebrated human resilience and resistance to circumstances, embodying the portrayal of outstretched arms.

The current configuration of the group is designed in a way that allows for a sequential and chronological interpretation of a series of events unfolding in three distinct acts – starting from the right side, where the elder son is cruelly attacked by threatening serpents. The positioning of the figures in the composition suggests a narrative in which the young man still holds a glimmer of hope for escape, presenting his persona as an embodiment of the developing drama, which is only in its initial stage. Through the image of Laocoön, we witness a poignant depiction of an unyielding and desperate struggle against inexorable forces of destiny — among the culmination of tension, the Trojan priest attempts to fend off the impending doom, culminating in the final, dramatic attempt to extricate himself from the serpentine entanglement. The composition reaches its resolution with the representation of the younger son, who seems resigned to his fate, relinquishing all resistance, succumbing to the encroaching shadows of death, overcome by the relentless hand of destiny. In this somber spectacle death reaffirms its undeniable sovereignty over the unfolding narrative.

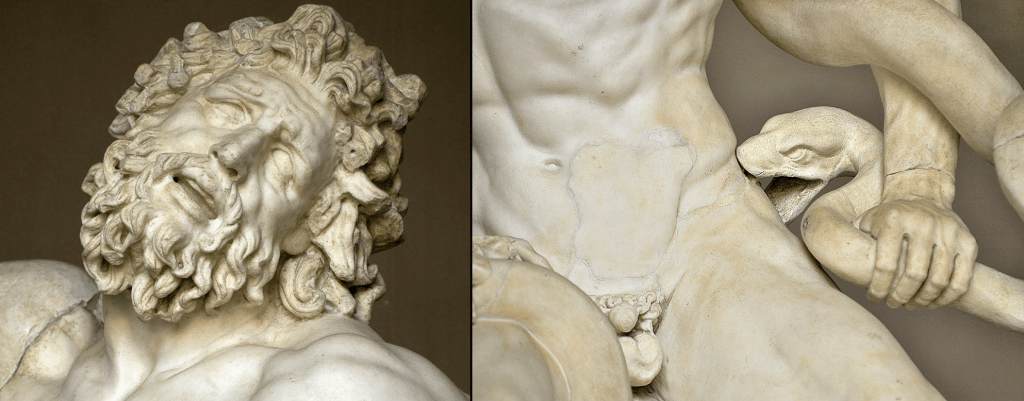

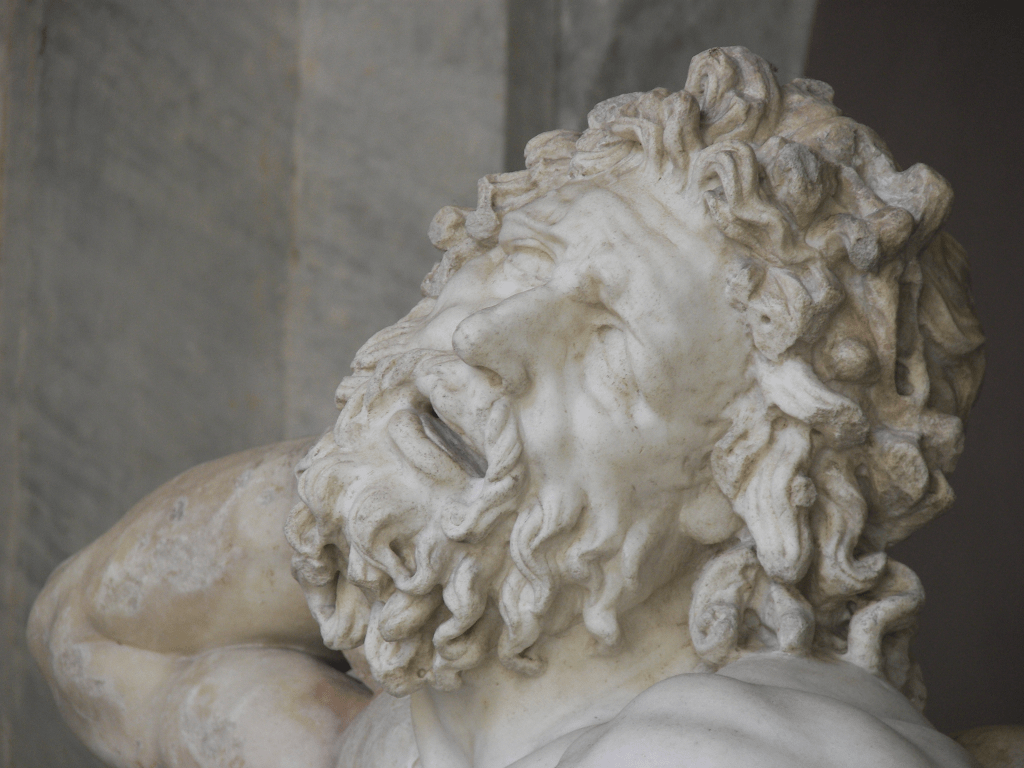

The portrayal of the elder son encapsulates the inaugural act of this unfolding tragedy, capturing the moment when he stands at the threshold of impending death — his form exudes urgency and agility, yet the serpents have not fully ensnared his body. Despite the palpable terror etched on his face, the youth exudes an aura of resilience and possibility. In the depiction of Laocoön, a deep well of emotional intensity is unleashed. The contorted posture of the priest conveys the zenith of tension, effectively crystallizing the apex of the dramatic arc. Through the countenance and stance of the Trojan priest, countless emotions are conveyed, from anguish to suffering to bravery, maintaining an air of ethereal beauty, dignity, and regality. In opposition, the representation of the younger son embodies a state of utter helplessness and extreme vulnerability in the face of the surrounding inexorable circumstances. The limp muscles and passive, shifting movement of his form, epitomize the ancient Greek belief in the inevitable decree of fate imposed upon mortals, underscoring the futility of resisting a fate predetermined from above. The profound passivity and helplessness exhibited by the boy’s physical form led many to interpret his character as already falling to the clutches of death. Particularly significant is the symbolic intertwining of the father and the younger son through the serpentine coils enveloping Laocoön’s right leg and both legs of the boy, symbolizing mutual bonds and shared destiny that binds them eternally.

The primary characteristics of Hellenistic sculptures encompass a wide range of diversity, subtlety, and complexity, showcasing innovative tendencies that were not tantamount to outright rejection of the classical legacy. It is noteworthy that Hellenistic art does not signify a departure from classical art but rather a progression on a larger scale. This measure extends beyond just the physical size of artworks but includes a broader exploration of themes, deeper emotional expressions, and a wider spectrum of subjects. One of the distinctive features that emerged during this period was the adoption of Baroque elements, characterized by a penchant for grandeur, the proliferation of colossal structures in architecture, and the incorporation of expression, pathos, and dynamism into artistic creation. The Baroque movement in Hellenistic art was known for its extravagant forms, stark contrasts between light and shadow, and exaggerated muscularity of depicted figures — traits that are also synonymous with the essence of the contemporary baroque art. Hellenistic art marked a transition from the classical simplicity of earlier periods towards the newly discovered inclination for grandeur and magnificence.

The Laocoön Group stands out as an excellent example of the characteristic features associated with the baroque movement in Hellenistic sculpture. It is characterized by elements such as deep drama, striking interplay of light and shadow, and highly pronounced musculature, which exudes a sense of dynamism. The palpable corporeality of the sculpture’s surface, skillful rendering of light and shadow effects, and unprecedented levels of agony depicted by the figures align with established traditions of “baroque” artistry. Furthermore, the Laocoön Group distinguishes itself with theatrical features, emblematic of Hellenistic sculpture, including dynamic interplay of light and shadow, a sense of movement and vitality conveyed through the bodies, and tactile sensuousness of its surface.

The baroque essence of Hellenistic sculpture is primarily defined by its portrayal of key moments of dramatic confrontation, intensifying overall dynamism, expressive power, and dramatic impact of the artwork. Within the context of the baroque movement in Hellenistic art, the representation of fully action-packed moments holds significant importance, contrasting with the traditional focus in classical sculpture on depicting figures in a state of rest before or after an event. Thus, the viewer is immersed in the very heart of the action, experiencing heightened immediacy and vitality that defines the baroque aesthetic of the era.

Ancient Greek artists possessed a profound understanding of human anatomy, enabling them to depict it with unparalleled precision and attention to detail. This ability was particularly evident in the Hellenistic era, a period marked by the creation of sculptures characterized by realistic, and at times starkly naturalistic features. While verism played a significant role in their artistic endeavors, it is worth noting that ancient Greeks often prioritized beauty over strict realism, a sentiment exemplified by the Laocoön Group, where the idealized notion of beauty transcends mere factual accuracy.

The legacy of classical art persisted in Hellenistic art through the continued celebration of the inherent beauty of the human form, albeit with a noticeable shift towards more corporeal and sensual representation. This departure from the classical aesthetic of perfect and transcendent beauty towards a more tangible and emotionally charged portrayal was accompanied by a persistent emphasis on heroic postures, even in scenes requiring depiction of brutality, suffering, or agony – traits that the ancients would describe as suffused with pathos. While tragic narratives from mythology only came to dominate in the Hellenistic period, it was during this time that their artistic interpretation reached new heights of expression and sublimity, exemplified by the masterful execution of the Laocoön Group.

Charles Darwin, in his observations, emphasized the ancient sculptors’ ability to capture the essence of despair in their works. Pointing to the Laocoön Group, he noted the perceived anatomical inaccuracy in the form of transverse furrows carved on the forehead by Greek artists. Despite this departure from anatomical correctness, Darwin argued that the deliberate choice to prioritize aesthetic appeal over strict adherence to reality was a conscious artistic decision. He believed that accurately reproduced rectangular furrows would not have the same visual effect and magnitude when immortalized in marble.

In conclusion, the Laocoön Group stands as a masterpiece of Hellenistic sculpture, embodying the dynamic and expressive qualities characteristic of the baroque movement within that era. Its portrayal of dramatic confrontation, emotional intensity, and exquisite craftsmanship exemplifies the pinnacle of artistic achievement in ancient sculpture, showcasing the enduring legacy of classical artistry infused with innovative tendencies of the Hellenistic period. Through its intricate composition and profound symbolism, the Laocoön Group continues to captivate and inspire viewers, transcending the boundaries of time and culture.

Leave a comment