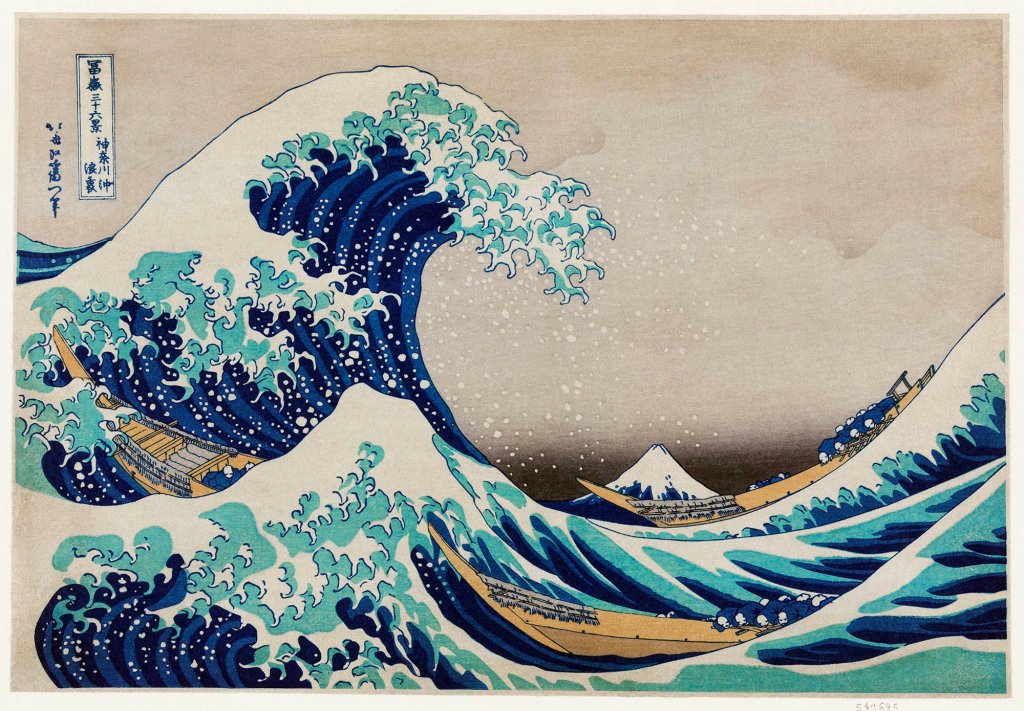

Colors have their own souls, hiding secrets and immersing themselves in a dark past. Every color present in great works of art, from ultramarine, which Johannes Vermeer wove into the turban of his Girl with a Pearl Earring, to the fleeting red blazing in the fiery sky of Edvard Munch’s The Scream, carries an extraordinary story. An example can be the fascinating shade of Prussian Blue, unexpectedly connecting Hokusai’s Great Wave off Kanagawa with Picasso’s Blue Room.

Creator: rawpixel.com)

Without the accident in an alchemist’s laboratory in Berlin in 1706, works by Edgar Degas or Claude Monet might not have exuded their mysterious power.

The beginning of this remarkable story took place when the German occultist Johann Konrad Dippel stained a recipe for an illicit elixir that could cure all human ailments. Born thirty years earlier in Castle Frankenstein, Dippel, suspected of inspiring Mary Shelley’s character Dr. Frankenstein, was discarding a failed combination of wood acid and bovine blood when the dye manufacturer he collaborated with interrupted him.

The missing red dye forced the manufacturer to reach for Dippel’s discarded solution, add a handful of crushed red beetles, throw the pot back on the fire, and start stirring. Soon, both were surprised to observe what emerged in the cauldron: not red, but a deeply shimmering blue, rivalling the brilliance of ultramarine, cherished for centuries as a precious pigment, more valuable than gold.

Artists quickly embraced Prussian Blue (named after the region of its accidental creation), saturating their works with new levels of mystery and intrigue. The secret lies in color. Just as the etymology of words enriches our understanding of poems or novels, the origin of color shapes the meaning of masterpieces in which it appears.

Invented by Stone Age cave dwellers, clever scientists, cunning fraudsters, and greedy industrialists, colors defining the works of artists from Caravaggio to Cornelia Parker, from Giotto to Georgia O’Keeffe, pulsate with fascinating stories. While Van Gogh may have incorporated a touch of so-called Indian Yellow into the shape of the moon in the corner of Starry Night in 1889, the vivid pigment still retains the aura of its tormented origin—distilled from the urine of cows fed only mango leaves. The way of creating color matters to the color itself.

Below is a selection of great works whose deep meanings are uncovered by delving into the origins and adventures of the colors they contain.

Orange: Orange chrome in Flaming June by Sir Frederic Leighton (1895)

The famous portrait of a slumbering nymph by Sir Frederic Leighton, Flaming June, seems to embody the lightness of carefree summer drift off. However, the way it slides below the horizon and the view of a branch of poisonous oleander within reach of a resting arm introduce motifs of death and burial into an apparently lazy landscape. Despite this, Leighton cleverly showered her supple silhouette with hectares of orange chrome—a relatively new pigment whose production in the 19th century became possible with the discovery of vast underground deposits near Paris and Baltimore, Maryland. An underestimated mineral, chromite, can be transformed into transcendental brilliance. Covered in orange chrome, Flaming June is not a mortal to be buried but becomes a treasure that can always be unearthed—an undying icon of endless beauty.

Creator: Art Renewal Center | Credit: Art Renewal Center via Picryl)

Green: Emerald green in Summer’s Day by Berthe Morisot (1879)

Some suspect that Scheele’s Green, the toxic green pigment adorning the bedroom wallpaper of the exiled Napoleon Bonaparte on the island of Saint Helena, may have slowly poisoned him, leading to his death in 1821. Half a century later, the French painter Berthe Morisot reached for emerald green, a close relative of the ominous Scheele’s Green, to cover the sky in her painting Summer’s Day. Although this work seems to capture two young women on a boat, drifting carelessly on the rippling water, there is something unsettling in the atmosphere they breathe. Emerald green, also saturated with arsenic, gives the scene an unsettling green—one that stirs and drills.

White: Lead white in Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl by James McNeill Whistler (1861-2) White has its dark side. Just look at Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl by James McNeill Whistler, whose title itself almost tries too hard to hide the dirtiness of its origin. Although the painting may seem emblematic of immaculate purity, it relies on the dirty pigment: Lead White. To obtain this pigment, strips of lead are placed next to a basin of vinegar for a month in a clay vessel surrounded by piles of fermenting animal dung. The combination of acetate, created by the proximity of lead and vinegar, with the carbon dioxide vapors emitted by fermenting dung, gives a fluffy white patina on the lead strips, which was both alluring and deadly. As early as the 2nd century, the Greek physician and poet Nikander of Colophon described lead white as a “hateful mixture” that could cause profound neurotoxic effects in those who collected it. However, the origin of lead white, instead of tarnishing Whistler’s work, unexpectedly sheds a positive light on the painting and suggests what we all hope for: that art has the power to transform us, regardless of our past, into something beautiful and new.

public domain image of painting from the National Gallery of Art nga.gov

Black: Black bone in Madame X by John Singer Sargent (1883-4)

When John Singer Sargent revealed his portrait of Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, the wife of a French banker, at the Paris Salon in 1884, he caused a scandal. It is said that the artist’s decision to let the right strap of her tight black satin dress dangle seductively from her shoulder (a detail he later removed) was too much for the contemporary eyes. But there is more than a spicy wardrobe malfunction that unsettles in this painting. Sargent eerily rendered Gautreau’s pale skin (which he created from an interesting combination of lead white, pink madder, zinc red, and viridian) with a pinch of ancient Black bone—a substance historically derived from crushed remains of burned skeletons. The mysterious ingredient complicates Gautreau’s dazzling complexion. The black bone transforms the portrait into a reflective meditation on the transience of the body, blurring the line between desire and decay.

In conclusion, a journey through the history of art through colors reveals not only the beauty of composition but also the fascinating stories that these colors carry. Each pigment, from Prussian Blue to Emerald Green, bears traces of accidents, experiments, and extraordinary discoveries. They are like mysterious signs on the canvas, animating works of art we thought we knew inside out.

Examples like Prussian Blue, connecting Hokusai’s Great Wave with Picasso’s Blue Room, or the Black Bone in Madame X by John Singer Sargent, show how fate, accidents, and moments of inspiration shape what we see on the canvas. These color stories become a metaphor for the artworks themselves—full of unfathomable mysteries waiting to be discovered.

While artists reach for these pigments to give their works new dimensions, we, as observers, are given a key to understanding why works of art have such a profound effect on our emotions and imagination. Colors, as storytellers, weave narratives that resonate with the human experience.

The stories of Orange Chrome in Flaming June, Emerald Green in Summer’s Day, Lead White in Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl, and Black Bone in Madame X exemplify how the origin, composition, and application of color contribute to the deeper meaning of each artwork. They highlight the transformative power of art, transcending its physical form to provoke contemplation and reflection on the complexities of life.

In essence, colors in art are not merely pigments; they are conduits of history, emotions, and cultural significance. The accidental discoveries, alchemical experiments, and intentional choices made by artists and pigment manufacturers have left an indelible mark on the canvas of art history.

In essence, the story of colors in art is a narrative of perpetual discovery—a journey where accidents become innovations, experiments become masterpieces, and pigments become time capsules of human expression. It is an invitation to explore the alchemy of creativity, where every stroke of the brush is a brush with history.

So, let us continue to unravel the stories woven into the colors that grace the canvases of artistic genius. As we stand before these masterpieces, may we appreciate not only the visual splendor but also the vibrant narratives that unfold through the kaleidoscope of colors. For in the world of art, each color is a chapter, and every masterpiece is a timeless story waiting to be read anew.

Leave a comment