The embrace immortalized in Gustav Klimt’s renowned painting, The Kiss, might initially appear to epitomize romantic love. However, delving into the life of the Austrian symbolist painter reveals a more intricate and platonic narrative behind this masterpiece. Let’s delve into why this celebrated artwork might not depict love in the conventional sense, but instead, narrates a nuanced tale of unfulfilled connections.

Before unraveling the romantic intrigue within The Kiss, it’s crucial to comprehend the enigmatic artist himself, Gustav Klimt (July 14, 1862 – February 6, 1918). As a symbolist painter and graphic artist, Klimt’s distinctive style renders his works instantly recognizable. Despite his artistic romanticism, Klimt, as an individual, was far from a romantic soul. Intimacy eluded him, and establishing genuine romantic relationships proved to be a struggle.

Residing with his mother and two unmarried sisters, Klimt returned home every evening, nurturing and cherishing his family. Though never married, he fathered at least seven children with four different women. The paradox of Klimt’s love life challenges the notion that someone incapable of love could create an artwork celebrated as one of the most romantic paintings in art history—a misconception that we aim to dispel.

Creator: rawpixel.com

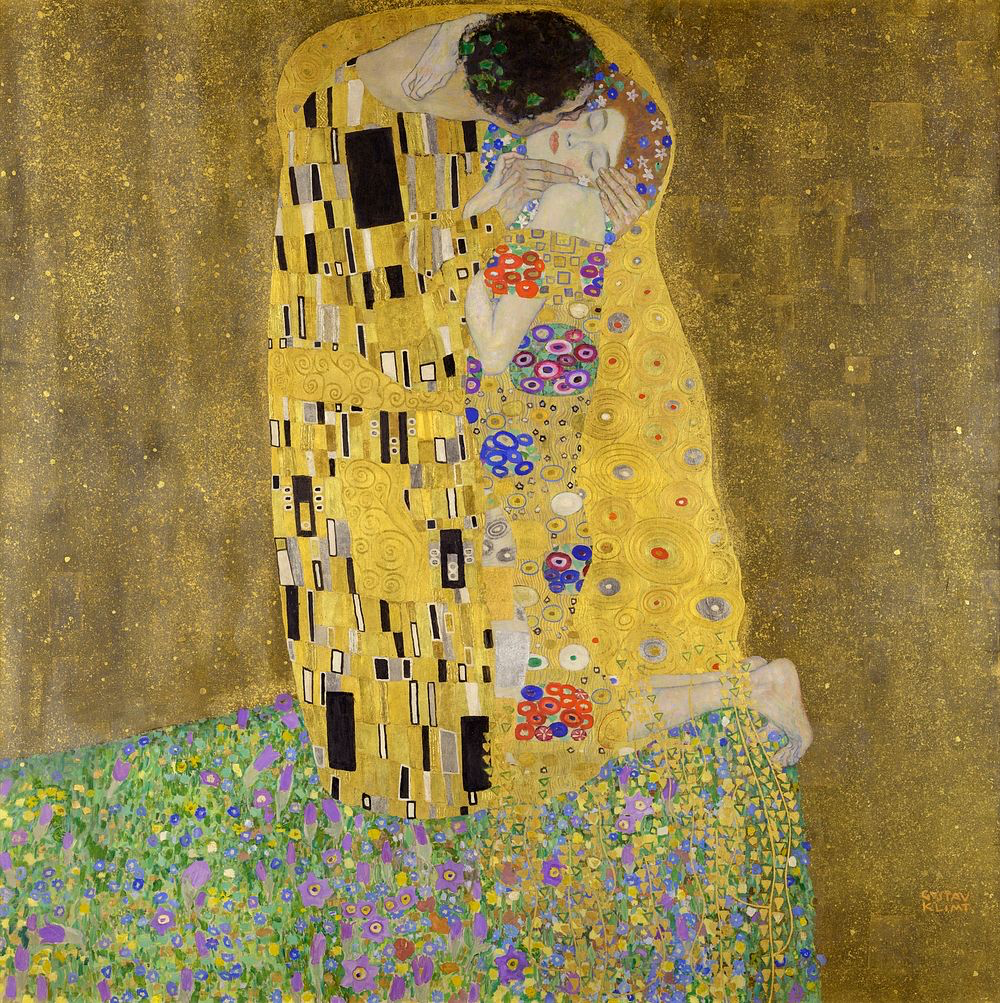

The Kiss by Gustav Klimt (1907–1908) portrays a couple passionately kissing, draped in golden robes, seemingly naked underneath. The ground is adorned with flowers, and they stand at the edge of a precipice. Both figures wear wreaths on their heads—the man with a vine wreath and the woman with a floral one. Significantly, laurel leaves surround the woman’s legs, suggesting her integration into nature.

The painting draws inspiration from the myth of Apollo and Daphne. In this myth, Apollo falls in love with the nymph Daphne, who rejects his advances. Apollo persists in his pursuit, leading to a desperate attempt to force himself upon her. Daphne’s father intervenes, unwilling to let his daughter become a victim of Apollo’s persistent advances. Faced with Daphne’s desperation, Peneus transforms her into a laurel tree, fulfilling her plea for protection against Apollo’s amorous pursuit. Daphne’s transformation into a tree becomes her sole salvation from Apollo’s ill intentions, simultaneously leaving behind an enduring beauty in the form of perpetually green laurel leaves.

While Klimt’s portrayal may not explicitly depict Daphne’s transformation, the desperation and submission are evident. A striking contrast emerges when comparing Klimt’s interpretation with Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini’s sculpture, where the metamorphosis is more apparent. Daphne’s attempt to escape Apollo’s grasp is vividly captured by Bernini, emphasizing power dynamics and Daphne’s struggle.

Ovid, in his Metamorphoses, describes Daphne’s transformation:

(…) From her limbs, the warmth and sense depart,

A chilly numbness seizes every part;

(…) The boughs of bay (for such the crown she wore)

Shade her fair limbs, and leafy garments more.

Her very voice is heard, but changed from man,

To boughs and leaves she strives to tell her pain.

And now the god, impatient to possess,

Spreads out his arms to clasp the lovely tree;

But the fair tree avoids his eager embrace,

Too conscious of her own unblemished charms.

Klimt’s The Kiss, in its subtle depiction of the Apollo-Daphne myth, challenges viewers to see beyond the surface of romantic allure. The painting becomes a testament to the complexities of love, weaving together elements of desire, surrender, and the inevitable forces that shape human connections.

Leave a comment